OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Soft Science Fiction

On November 16th, 2018, Aimee Bahng, assistant professor of Gender and Women’s Studies at Pomona College will deliver a closed seminar and a public lecture at the West Hollywood Public Library as part of the WHAP series curated by Sara Mameni on behalf of the Aesthetics & Politics department at California Institute of the Arts. The public lecture, entitled, “Toward a Transpacific Undercommons,” will begin at 7:30 pm.

One of the opening quotes of the introduction of her book emphasizes on the importance of keeping in mind the relationship between culture and economy, which is a very insightful way of starting an introductory essay called “On speculation”. The link and arch she will draw through this essay is the one between financial speculation and speculative fiction.

This book puts into conversation speculative finance and speculative fiction as two forms of extrapolative figuration that participate in the cultural production of futurity.

In order to achieve this, she steps into two fields, “an emerging field that could be called critical finance studies” and “a longer standing field called feminist science studies, which trained me to beware of the ‘god trick of seeing everything from nowhere.'” It could also be said that in between these two fields (or throughout them) she is also using the methodologies and approximations of post-colonial, or decolonial studies, especially in the later applications of the concepts she introduces in this essay in her later analysis of works of culture.

To think through this decolonial approach, between critical finance studies and feminist science studies, I will concentrate in utilizing these concepts and ideas in the analysis of a decolonial work of soft science-fiction from Brasil, Branco Sai Preto Fica (White Out Black In, Adirley Queiros, 2014)[1]. I use here the term soft science fiction as a companion to Bahng’s ideas on rejecting the term science fiction and using speculative fiction instead. In her introduction, Bahng insists on the importance of turning away from science as the only possible source of knowledge and content towards alternative sources less attached to the dominant culture. She also emphasizes in the importance of having a term that will not only include fictional work that is focused on science and technology but to open up to other genres such as fantasy, horror, and historical fiction. I see this move as a fundamentally political approach to thinking through works of fiction and culture, as it creates a space in which the values of traditional science fiction, and with them, its categories and aspirations in quality, will not dominate the spectrum of the possible in creation and culture. I believe that by opening up the possibilities she is creating a model of analysis that will have the tools to focus on less canonical work.

As science fiction does, fantasy, horror and historical fiction work with ideas of the world and of the real in order to create alternative times and spaces in the shape of fantasies and nightmares. Even in the case of historical fiction, the ways in which elements of the world are portrayed create perceptions and sensations that can change the relationship a subject can elaborate with reality. This is related to her rejection of the word future and its replacement with the word futurity. Futurity is a speculation, but one that comes from below; a way of imagining that materializes alternative ideas of the future, ones that will create a space and time discretization in the capitalist context. I believe Adirley Queiros’s soft science fiction fit squarely in this category, creating a narrative of the forgotten to create a new speculation on the possible.

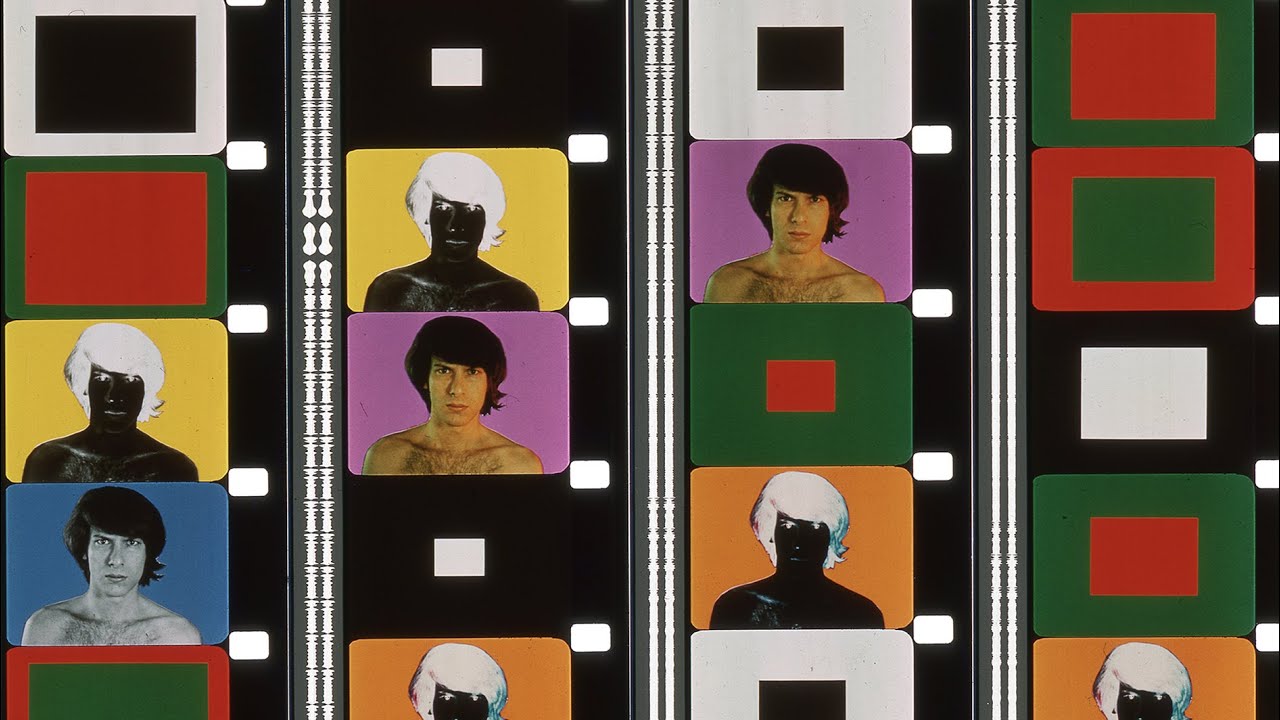

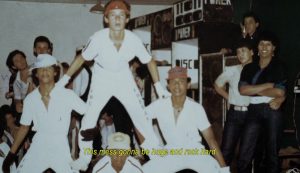

Branco Sai Preto Fica (Adirley Queiros, 2014)

Branco Sai Preto Fica (Adirley Queiros, 2014)

His second film suggests that science fiction and documentary are the same things. First, because he understands that filmmaking finds this distinction irrelevant. Second, because this idea fits with the place from where he comes from and which he shoots, a city whose creation is a synthetic intervention in history by a quirurgical procedure. I think he is trying to explain that another timeline did appear in the moment in which the former inhabitants of the Brazilian favelas were moved to Ceilândia.

–Martín Álvarez, Our Music

Branco Sai Preto Fica is also a documentary. Allow me to give you some context. The filmmaker is a former soccer player whose career ended due to injury, which partially ended his aspirations of upward class mobility. He was born and raised in Ceilândia, a satellite city to Brasilia. Ceilândia is one of the areas that the state created for the lower classes, as there is no room in the urban planning for the workers who built the city. The population of Ceilândia is usually harassed by the racist Brazilian police, which criminalizes every person’s moves, especially black males. As with any artificial environment, it took a while for Ceilândia to create a community out of the neighborhoods, and one of the community-building aspect in the life of the people of Queiros’s age has been Hip Hop[2]. Back in Brasilia their contemporaries, the upper classes youngsters would listen to foreign rock and roll from which they drew inspiration for creating their own movement called Rock Brasilia. In Ceilândia, they listened to foreign and local [3] Hip Hop and created a community around it, both in resistance and pleasure. Every weekend night, they would have dances promoted by local DJs. Some people spent the whole week preparing choreographies for the weekend in order to gain popularity. But many times the dancers were forced to end due to police harassment. The police would ask the white people present to go out home and the black people to stay, after which the harassment became physical violence. The film brings this past into the present, both through oral history and the use of pictures from the time.

Branco Sai Preto Fica (Adirley Queiros, 2014)

Branco Sai Preto Fica (Adirley Queiros, 2014)

The film has three main characters, all of them marked by this police violence. The first one is Marquim, one of the old dancers from the parties who now has a radio show dedicated to music. He is in a wheelchair because of the racist police. In the first sequence of the film, he goes down the stairs of the basement in which he lives. He goes down, prepares his record player and microphone, and starts with the introduction of his show. He plays his monologue as if he was in the time and place of the events speaking to them in present, even if he is still in the basement radio station. He narrates how he goes out of his house, heads downtown, goes to his friend’s shop to drink, gets to the club, sees the big line, doesn’t want to wait in line so he cuts it through his friends at the door and goes in. He spots a girl he likes and he tries to impress her with his moves, people are dancing, music is playing. Suddenly, something is going on at the door. The police enter, gas everywhere, they stop the music and start messing with the crowd. Girls on one side, guys on the other, whites out, blacks in. The police ask for guns, no one is armed. The film fades to white and we hear a gunshot. Without having to finish the anecdote, we know what happened to his legs: the shot was directed to him.

The second character is Sartana, a man that is missing one leg and works making prosthesis with the things he finds in junk shops or are disposed of by medical centers. He lives in a place similar to the one Marquim lives, adapted for his disability with a homemade elevator, and he visits people in their homes to replace or repair their mechanical legs. He was also a hip-hop guy. In a police action, a horse fell onto him, resulting in him losing his leg.

The third character is a time traveler that comes from Brasil of the future. His mission is to find Sartana and the others who were harmed by the police to reopen cases against the perpetrators of violence and compensate the families. When he receives communications from his superiors, they call the past “the territory of the past,” creating an illusion not only of time travel but space travel. He walks around Ceilândia looking for the witnesses and victims but, at the same time, he observes and despises what has been done to this population, who have been displaced in such a violent way. The traveler and starts to think about staying.

In the film, our present is seen as the past, which creates distance from it. In the film, documentary and science fiction are very much alike. By creating this distance, it that establishes its own time. An observation of the situation can be made that makes the whole thing dystopic. A satellite city created for having the poor out of sight, a series of police misconducts that go unpunished, a series of precarious but well-functioning technologies that make the lives of the characters a little easier and will end up being the tools for resistance. On the other hand, the future from which the traveler comes is a symbolic space in which things are a little better because of the possible resistant actions. The future is not the kingdom of technological advancement but of racial justice. But it is also something that needs something from the past, which is the present. There are things that can be done against this dystopic present[4].

Together, they facilitate temporal and spatial disorientations that intervene in a neoliberal fantasy of a seamless world unified under the sign of global capitalism for the global (financial) citizen.

Queros uses speculative documentary to create the disorientation Bahng is writing about. The history of Ceilândia is a marginal and untold one, which is very far away from the imaginary of traditional science fiction. Its objective is not only to create a different futurity but also to re-write the past through this disorientation, bringing to the front stories and events that were erased in order to intervene both the present and the future. The film itself is a way of time traveling to the early nineties and its hidden histories of violence, a feminist decolonial approach.

Branco Sai is not only decolonial in its plot and contents, but it is also decolonial in its relationship to the aesthetics of science fiction. Everything in the film is made out of found materials, things from the garbage, from the junkyard. Parts of cars and machines are put together. The way the film relates to the belief in its science fiction elements is by creating a different contract – one in which the goal is not to imitate as closely as possible the usual science fiction costumes and effects, but to mock them, to create them from scratch with bad materials and to create fiction with a fully believable fiction that has its own rules. The space traveler’s ship is a 40-foot container illuminated with the flickering light of a disco ball, which remains in the offscreen space. This creates a new convention for science fiction, one that comes from Ceilândia to the outside, comparable to what Bahng says is “far away from capitalist imagination as possible.” The goal is not to imitate but to question and re-write. The value of the film is in its political discourse and the aesthetic ideas that are provided, not in production value.

There is an economic side to the way the film relates to the traditions of science fiction, also moving away from capitalist imagination. As an act of refusal, the film does not hide every moment when the cheap materials used to make costumes and objects interrupts. It is not that the crew did what they could to make the film attractive, but that they chose not the erase the conditions of its production. Materials that obviously came from the junkyard are up front and visible – they are fully-recognizable as what they were before. All a consequence of the production design being made by friends who have their own ways of confronting the economic situation that belongs not only to the film, but to all of their lives.

In addition, the way in which the plot moves in the film is very obscure. There is no imposition of conflict other than a small task that the traveler has to achieve: to find proof of police violence. The other characters just live their lives, do their work, and at some point, the films ends. The closing credits show a fantasy that they all shared, that may or may not be materializing right now: Ceilândia blown into pieces by a giant spaceship. Nothing is conclusive but the decision of taking the science fiction to action. As Bahng characterizes in her text, “tidy resolution is not an ultimate goal”. The clarity of a plot, of objectives, of actions is not something the film concentrates about. The thing the film does concentrates around is the life experience of a certain group of people that liked the same things and suffered the same kinds of violence. The approximation to people’s lives and work is what makes the plot obscure, as they have been around before the film started and they will continue after. There is no tidy resolution for the intertwined conflicts that surrounds these people lives because as the film ends, the struggle goes on against the acts of violence of speculative capitalism.

I believe the model that Amy Bahgn proposes is extremely useful for many reasons. The importance of turning away from dominant narrative models and approaching alternative sources of knowledge, such as Ceilândia’s hip-hop culture, can make room for different existences and create safer spaces for them both in fiction and beyond. The uses of speculative fiction and not science-fiction (in this case and many others) also make room for alternative ways of organizing time and space in narratives in a way in which the experience could approach the realities of others at the same time as it brings less traditional materials to craft those narratives (a 30-feet container, for example). This model helps replace the traditional values of science fiction with less rigid ones, more open to depending on the source communities and materials, opening up the spectrum of the possible. Lastly, I think this model is very useful to analyze the relationships between fiction and economy both in the making and the thinking through. By doing this, new alliances between communities that relate to this materials can be created, ones that could go further, even into action.[5]

Branco Sai Preto Fica (Adirley Queiros, 2014)

[1] Part of this thought comes from the discussion of this material with my colleague Nathanael Hency, who is thinking through this film for his MA thesis.

[2] Here there is a playlist with the songs that appear in the film

[3] Lyrics from Panic in the South Zone by the Brazilian Hip-hop band Racionais:Então quando o dia escurece / Só quem é de lá sabe o que acontece / Ao que me parece prevalece a ignorancia / E nós estamos sós / Ninguém quer ouvir a nossa voz / Cheia de razões calibres em punho / Dificilmente um testemunho vai aparecer / E pode crer a verdade se omite / Pois quem garante o meu dia seguinte / Justiceiros são chamados por eles mesmos / Matam humilham e dão tiros a esmo / E a polícia não demonstra sequer vontade / De resolver ou apurar a verdade / Pois simplesmente é conveniente / E por que ajudariam se eles os julgam deliquentes / E as ocorrências prosseguem sem problema nenhum / Continua-se o pânico na Zona Sul.

So when the day grows dark / Only who is there knows what happens / To what seems to me to be ignorance / And we are alone / Nobody wants to hear our voice / Full of reasons in a fist / Hardly a testimony will appear / And you can believe that the truth is omitted / For who guarantees my next day / Vigilantes are called by themselves / They kill humiliate and shoot randomly / And the police do not even show / To solve or to find the truth / Because is simply convenient / And why would they help if they find them delinquent / And the occurrences continue without any problem / The panic in the South Zone continues.

[4] In Queiros’s next film an army for the resistance will be created between people from the earth and beyond. The film is placed during Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment. I can’t wait to see how he is going to go against the monstrous Bolsonaro in the new one.

[5] For more on Queiros’ film and process can be read in this interview made by Martin Alvarez and Ramiro Sonzini