OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Putting Pain on the Map: Ronak Kapadia and the Queer Calculus of Wafaa Bilal

The following post responds to Ronak K. Kapadia’s text ‘Up in the Air and on the Skin: Drone Warfare and the Queer Calculus of Pain’ published 2016 in Critical Ethnic Studies: A Reader, in which he discusses the works of contemporary New York-based Iraqi artist Wafaa Bilal in relation to the US warfare in the Middle East, as well as, to a lesser extent, a yet unpublished text, due to appear in 2019, investigating works of the artists Chitra Ganesh, Mariam Ghani and Rajkamal Kahlon and their responses to the US forever war. Kapadia is Assistant Professor of Gender and Women’s Studies and affiliated faculty in Global Asian Studies and Museum & Exhibition Studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He holds a Ph.D in American Studies from New York University. His research interests include critical ethnic studies, women of color and transnational feminisms, queer of color critique, Asian American studies, South Asian/Arab/Muslim diasporas, critical prison, military, security, lawfare studies, visual and performance studies, affect and new materialisms, radical social movements and US Empire.

I think in recent months – in fact ever since the last election in the U.S. – I have heard virtually nothing about the U.S. American military ventures into the Middle East and South Asia. Trump’s continuous focus on international trade and domestic affairs, as well as the U.S.’ physical border has pushed discussions of the ‘forever wars’ of the recent years into the background. While I now feel as if the Obama administration had been probed on their military exploits almost daily, with shocking numbers of drone strikes as one of the key topics, the conflicts which are still ongoing, barely break through the news cycles anymore. And yet, the reverberations of these discourses can still be felt. Out of the list of countries affected by Trump’s infamous travel ban for example, Iran is the only one that would not also show up on a map of countries affected by U.S. military presence and drone strikes (yet).

Paradoxically, many of those that fall victim to the “war on terror”, flee to the very epicenter of the power that is making their homes unsafe in the first place. Forced to seek refuge in the U.S. yet now simultaneously banned, they find themselves in an existential limbo, revealing the complicated mesh of intertwining forces and narratives affecting them each and every day. Under the new administration the media might be focused on other issues, but the U.S. counterinsurgency warfares continue to affect millions of people both abroad and within its own borders.

Ronak Kapadia’s work investigates U.S. empire, its counterinsurgency warfares in South Asia and the Middle East, its relation to local populations, as well as critical responses by diasporic artists with a focus on queer and feminist practices. By extensive readings of selected artworks dealing explicitly with the military warfare, interrogation and surveillance practices we can gain access to alternative ways of understanding and responding to the U.S. forever war. Kapadia introduces a critical vocabulary through which to understand the artworks’ endeavours to analyse, challenge and repair practices and narratives produced by the U.S. military apparatus. Thus it becomes part of a wider project of ‘questioning the abstractions and rationalities of U.S. imperial discourse and the statistical modes through which the collateral damage of counterinsurgency warfare is calculated’ (Kapadia 2016, 360).

The key concepts that are introduced in order to talk about the artworks and their projects are ‘Queer Calculus’ and ‘Warm Data’.

In the piece ‘Up in the Air and on the Skin: Drone Warfare and the Queer Calculus of Pain,’ Kapadia discusses the works of contemporary Iraqi artist Wafaa Bilal. Based in New York City, Bilal’s work tackles U.S. warfare in Iraq and explores the relations between the U.S. American state and the Iraqi people.

The focus of the text is Bilal’s 2010 performance piece entitled … and Counting, in which the artist transforms his body into a canvas by tattooing the names of Iraqi cities on his back and then, during a twenty-four-hour live performance, tattooing 105,000 dots onto this borderless map as audience members stand witnesses while a select few solemnly recite the names of Iraqis and Americans killed in the U.S. occupation since 2003. Five thousand dots are marked first in red ink to represent dead American soldiers. The remaining 100,000 dots, meant to memorialize the “official” Iraqi death toll from the war, are in ultraviolet ink, invisible unless viewed under a black light (ibid., 362).

Wafaa Bilal, … And Counting, 2010.

Wafaa Bilal, … And Counting, 2010.

The piece, Kapadia argues, can counter the predominant narratives of war and security on multiple fronts. The alternative, borderless map covering the artist’s back invokes and subverts processes of traditional military, aerial mapping, as employed for drone weaponry and by security experts. The “affective map” puts in question our common approach to war zones and our understanding of the data we are presented with. It may ‘provide diagnoses of and alternatives to the geopolitical and epistemological maps produced by the U.S. global security state’ (ibid., 365).

Tattooed into the skin of the artist, the work creates a map of pain, literally and in an abstract way by means of the topic it addresses. This tactile dimension may also challenge the general dominance of the visual as prefered organ for understanding and knowing. Yet, to see the artwork as not being concerned with the visual, or exchanging one sense for the other, would be reductive. In fact, to read Kapadia’s opening statement of paying close attention to the ‘nonvisual sensory elements’ as such a restructuring, or as a move away from the visual, would be a misunderstanding.

The artwork is still deeply and explicitly concerned with the visual. In fact, the visual has long been an important aspect of Bilal’s work, as are other works in his œvre that Kapadia mentions, reveal: in his 2007 performance Domestic Tension, Bilal was locked in a gallery space with a paintball gun, controlled virtually by visitors of a website who were able to shoot at Bilal.

Wafaa Bilal, Domestic Tension, 2007.

Wafaa Bilal, Domestic Tension, 2007.

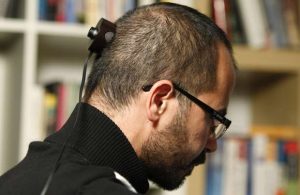

With more than sixty-five thousands participants firing at the artist, the work serves as a reminder of the affective distance operating in our engagement in contemporary warfare, where information is delivered to us coldly and at safe distance. It could even be argued that it is becoming the mechanic of warfare itself, when drone strikes, for example, remove the American soldier from the site of pain and destruction, becoming little more involved than the visitors of the website in Bilal’s work. It speaks of the environment of pain and surveillance, inescapable for many Iraqis. 3rdi provides another striking example with the artist’s engagement with the visual. In the piece, Bilal had a camera surgically installed on the back of his head.

Wafaa Bilal, 3rdi, 2010-11.

Wafaa Bilal, 3rdi, 2010-11.

The piece conjures an air of paranoia, of a constant wish to look over one’s shoulder. Simultaneously, the production of half a million random pictures speaks to the imperial collection of image material and surveillance data, posing the question what kind of image material is considered valuable, mappable and informative and which is simple “unintelligible”.

But rather than repeating or even simply countering the dominant visual narrative, Bilal’s works call into question the entire framework of the visual dimension. The ultraviolet dots, representing the official Iraqi death count, provoke a discussion on what is being seen and what is being disappeared in the first place. So while this artwork is certainly about a way of expressing and channeling pain, creating a map that is more than a logistical or strategic cartography but also a document of mourning, it becomes less about making these victims visible than to show that they have also fallen victim to an epistemological framework of exposure and disappearance which yet claims to be neutral or objective. Vision’s direct life-line to truth becomes exposed as already infused with politics.

The artwork opens up possibilities of alternative, affective, ways of understanding and engaging not merely by a transfer into the tactile sensory, but by exposing the visible as charged, produced and obscured. The exposure of pain and vulnerability is thus more than an addition to our knowledge of these wars but simultaneously asks us to think more carefully about other “facts” and the way they have been mapped out for us. The queer calculus is not an extension but ultimately “queers” the existing calculus of life which is considered countable, liveable and grievable. The queer calculus is in a way a direct response and alternative to the calculations of former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who, in a 1996 interview, justified the death of half a million Iraqi children under the U.S. embargo, calling the price ‘worth it’ (Albright in Kapadia 2016, 361). The work thus creates a platform for thinking more carefully about which lives “count” and which deaths are seen (as deaths).

However, it is only in this process of “queering” that Kapadia can satisfactorily ground his word choice. In the etymological sense of queer meaning “odd”, the term is absolutely appropriate. But as we know, queer has another meaning, far more political, and perhaps important. That this kind of engagement with vulnerability, affect and repair is very much in line with queer politics is clear. I agree with Kapadia that this provides ‘an opportunity to think anti racist, anti-imperialist queer politics anew’ (ibid., 373). Thus, I fully support the move of reading Bilal’s works for the purpose of a queer project. But I am not convinced if this potential for gleaning makes Bilal’s calculus itself “queer” per se. If the bridging to the queer project fails to be fully argued, we risk to reduce the meaning of the word and with it the struggle associated with it. It would also be a dangerous reduction, to simply assume from the use of the term, that queerness automatically brings a privileged access to affect, or sensation, or pain, or vulnerability – all of which is at risk of being implied through the reading of the work. There is understandable opposition to appropriating this term and a more explicit acknowledgement of its use as well as the underlying struggle would have benefited the interpretation. While I see why a connection can be drawn to the queer political project, I was left wondering what it is about the artwork itself that makes it ‘queer’ exactly, rather than being simply, say an alternative or affective calculus.

In Kapadia’s second text, which is scheduled to be published in 2019, he introduces the works of Brooklyn-based artists Chitra Ganesh and Mariam Ghani as well as Berlin-based American artist Rajkamal Kahlon, with a focus on their engagement with declassified documents. Similarly to Bilal’s work, these artists’ practices allow us to construct alternative modes of knowing and feeling how resistance operates in the face of U.S. forever warfare; Kapadia follows Ghani’s use of the term ‘warm data’ in describing their work.

‘Warm data’ provides a way of questioning and moving beyond dominant forms of experiencing military information, making us aware of what is considered vital information and what kinds of data are omitted or disregarded. Kapadia calls it a reparative feminist practice and believes it holds the key for a simultaneous analytic and antidote.

It does so in much the same way as Bilal’s ‘queer calculus’: neither of the projects are engaging in directly putting an end to the forever war or alleviating the pain of its victims. Rather, by foregrounding other ways of engaging the data, other ways of mapping, feeling and responding, it challenges the forever war’s epistemological context and the monopoly it has on narrative and meaning making. It is not a direct discussion of or argument against the U.S. military operations, drone strikes, interrogation techniques and detention strategies. Rather, it is about the visual, narrative and intelligence framework, in other words, the surrounding epistemological structure, which allows the military mechanisms and rhetorics of security to make sense in the first place.

This is how Kapadia argues that the artists’ queer calculus and warm data can function simultaneously in analytical and reparative capacity. They do not provide healing for the victims or interrupt the U.S. warfare immediately. Instead they present and call into question the way we are usually invited and engaged to see the conflict.

References

Kapadia, R. (2016). Up in the Air and on the Skin: Drone Warfare and the Queer Calculus of Pain. In N. Elia, D. M. Hernández, J. Kim, S. L. Redmond, D. Rodríguez, & S. Echavez See (Eds.), Critical Ethnic Studies: A Reader (pp. 360-375). Durham: Duke University Press.

Josh Widera is a graduate student of the Aesthetics & Politics program at CalArts.