OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Winnie Wong’s “Sub-Authentica”: The Liquidation of Authorship in Science and Pop Music

Shenzhen has a growing presence in the Western imaginary. The city’s reputation as a hub for unfettered technological innovation has earned it the nickname “Silicon Valley of China.” At best, this analogy is a massively reductive gesture towards Silicon Valley and Shenzhen’s mutual involvement in tech. At worst—and this should surprise no one—it contributes to an orientalist-inflected obfuscation of the logics underpinning Shenzhen’s booming tech sector, and the wider cultural implications of these novel capitalist practices.

Scholar Winnie Wong’s research operates at this gap between the Western imaginary and the industrial development of modern China. Her work works toward overcoming obstacles to understanding imposed by the bogus heuristics of the Western imaginary, as well as elucidating the distinct innovations to Western logics proffered by Chinese capitalism. In her paper “Speculative Authorship in the City of Fakes,” Wong discusses Shenzhen’s growing ascendancy in the field of bioinformatics, attributing the sector’s success in part to companies like BGI (formerly Beijing Genomics Institute), whose instrumentalization of “authorship” in scientific research papers contributed to its rise as a powerhouse in the industry.

Wong’s work typically approaches the “problem” of authorship as a problem of Western philosophy and aesthetics, frequently exploring the clash of logics between Western and Chinese aesthetic values through an art historical lens. So in this article, I want to import her observations on scientific authorship back into an aesthetic context: into the Western-dominated sphere of pop music production. The music industry is another site of conflict between varying logics of authorship, rife for exploration through the critical foundation that Wong has established. Prominent agitators in this clash of logics are catalog acquisition companies like Hipgnosis, whose experimentation with authorship deserves close inspection. Shelling out billions of dollars for legal rights to classic songs and artist catalogs, Hipgnosis’ business model acts as repository and gatekeeper of cultural history, wagering that authorship of present and future hits will increasingly rely on debts to prior artists—whether through samples, flips, covers, interpolations, or other likenesses. Clearly, there’s an active fracturing and distribution of authorship at play here that rhymes with BGI. But far from constituting a “BGI of the pop music industry,” Hipgnosis leverages authorship on the principle of debt rather than BGI’s emphasis on credit, marking an interesting divergence in their conceptions of future authorship.

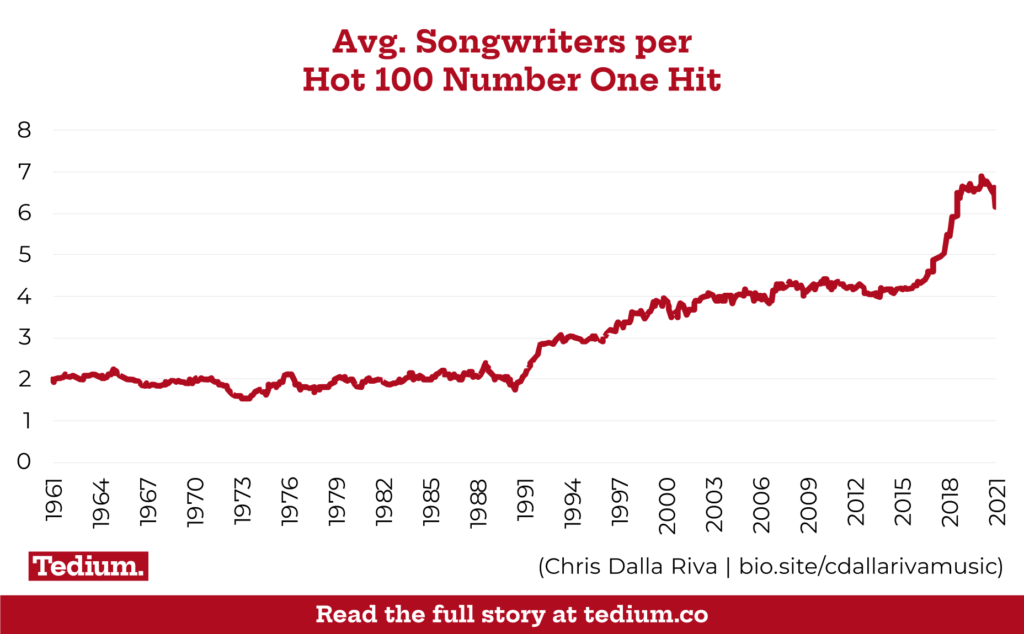

But let’s begin with the similarities: both Hipgnosis and BGI stage their interventions in milieux experiencing acute authorship inflation. In the music industry, a string of lawsuits over copyright have forced songwriters into painstaking practices of authorship attribution. Songwriters were particularly cowed by the landmark case in which Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams’ “Blurred Lines” was held to task not for copying Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give it Up,” but for its similar “feel.” After the lawsuit’s resulting $7.4 million payout, songwriters and publishers have the fear of God, prompting them to credit even vanishingly tangential contributors.

Take the 2018 hit “Sicko Mode” by Travis Scott feat Drake with its eye-popping thirty credited names. This song represents the extreme end of the spectrum, but nevertheless, average songwriters per Hot 100 Hit song is on the rise, currently hovering around 6.5. One trope of modern songwriting that contributes to this boost is the use of samples, which, in the case of “Sicko Mode,” can cause a chain reaction of attribution: the track samples a Notorious B.I.G. song, which itself samples three other hip hop songs, whose source material lies still further up the line.

The situation in scientific fields shows the same tendency toward exhaustive attribution. Wong notes that, preceding BGI’s intervention, scientific authorship was already far from the myth of the Einsteinian or Edisonian scientist, portrayed as an individual genius responsible for the discovery of natural facts. The truth is that lists of authors frequently stretch into the thousands when international research organizations like CERN are involved. This explosion of authorship is the result of stratification processes analogous to those occurring in the music industry, denoting the increasing granularization and abstraction of ownership metrics. CERN, for example, credits a standard list of authors running into the hundreds for any research paper produced using Fermilab’s Collider Detector. The credit is attributed whether these authors were actively involved in the experiment or not. It’s as if the material infrastructure of the Collider Detector is imbued with the labor and legacy of the scientists who maintain it, the use of which becomes akin to sampling their work.

According to Wong, BGI’s innovation was the simple application of an overt monetary value to authorial credit. Its access to state-of-the-art genomic sequencing machines gave the company a strategic infrastructural position in the globalizing field of scientific research. BGI didn’t just provide research teams a convenient means of outsourcing their computational needs—it also implemented deep discounts in exchange for bylines, where markdowns were based on the predicted prestige value of the study. In Wong’s words, “the higher the likelihood that the paper would be accepted by either Science or Nature [magazines], the lower BGI’s price for sequencing would be.”

BGI’s use of market logics to apply a credit value to authorship was a simple act of saying the quiet part out loud—obviously inclusion in a landmark study builds a scientist’s reputation and opens doors to future opportunities. Nevertheless, this tactic aroused grumblings in Western scientific communities over the vulgarization of the sanctity of scientific discovery. Wong remarks, “BGI’s ‘fee for service’ practice openly converts honorific values into monetary equivalents, quantifying the value of ‘collaboration’ underlying the production of scientific facts” and calling into question the “authenticity” of BGI’s use of authorship.

But there’s a similar quantification of “collaboration” occurring under Hipgnosis’ model of authorship as it attempts to revive past artists as present-day collaborators. Songwriter Rodney Jerkins, who sold his catalog to Hipgnosis, describes the nature of this speculative value:

What [Hipgnosis founder Merck Mercuriadis] has been trying to drill in myself and others is those songs hold value. It could be just a progression of a chord that sparks creativity for the next big hit from someone else. It may be a hook, maybe a verse within it. But don’t just leave your songs dormant sitting somewhere collecting dust. Really take a close look at everything that you have, and let’s try to find places for it to live.

Jerkins’ realization of a song’s untapped potential begins to reveal the ideological underpinnings of Hipgnosis’ catalog management structure: not only does it collect intellectual property to act as cultural landlord, it also actively endeavors to optimize the “dormant” potential of old songs, pitching them to beat makers, remixers, ad agencies, platforms, studios, etc. to re-seed their cultural relevance. Effectively, Hipgnosis reanimates the credit value and creative potential of the past. Taking advantage of the austere currents in copyright law, it seeks a future of pop music production in which access to their archival musical catalogs is a requirement to making hit songs. What this starts to look like is a system of feudal debt.

To a certain extent, Hipgnosis’ back-looking business model capitalizes on nostalgic affects—an inclination presumably driving the abovementioned bristly reactions to BGI’s use of authorship. In ideological form, nostalgia famously represents the reactionary desire to revive a lost authenticity. Both Hipgnosis and BGI’s critics locate the ideal of authenticity in the legacy values of Western culture. For all its progressive posturing, Hipgnosis’ treatment of song catalogs as investments preserves them as quantified units cultural history, rallying market forces toward the increased presence of the past. BGI’s investment in its own authorship, the success of which gives it increased influence over the future global scientific agenda, challenges the reproduction of historical Western value systems.

What does this mean for the Western conception of authenticity? Both Hipgnosis and BGI indicate that this concept belongs to the past. The difference is that Hipgnosis redeploys authenticity through nostalgia while BGI, according to Wong, “pokes fun at” its sanctimonious conventions. In fact, BGI seems to identify the notion of authenticity as incompatible with traditional academic training, encouraging promising university students to drop out before they are “deadened by academia.” Plucking students from the academy translates to a sort of ideological “de-skilling,” whereby students are saved from indoctrination into established mores governing scientific research. This relocates authenticity to a site below the discourses of the ivory tower, the historic seat legitimacy in the Western imaginary.

But of course the ultimate irony is that this new model of “subthenticity” is already present in pop music production, an open secret in an industry where pop icons perform songs written with production teams and fragments of other songs. It seems cultural investments in authenticity can be selectively suspended, postponing a confrontation with practices that the Western imaginary itself would dub a “de-skilling.” From the leaky concept of authorship, we witness companies like Hipgnosis attempt to channel the spillage back into the illusion of a past full of authentic artists with still more to offer—but what newness can we expect from past artists when their credit value comes from a sense of debt?