OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Theresa Cha: Identification and Disidentification

Introduction

In the Aesthetics and Politics Lecture Series of 2021, Latipa (Michelle Dizon), the Associate Professor of Media and Cultural Studies at the University of California, Riverside, introduces her upcoming film “The Absence” and its relationship to the legendary Korean American Artist Theresa Cha. The lecture highlights Cha’s posthumous book, Dictée, and how her legacy affects a potential rebellion against the documentary and the underlying visuality of colonial dominance. This essay explores the decolonial aspect of Theresa’s work and life. It extends to the queer concept of disidentification concerning Anne Anlin Cheng’s interpretation of Dictée as an anti-documentary documentary. Other case studies, such as Monyee Chau, a contemporary Chinese American artist, are examined for evincing the artistic tension between identification and disidentification.

Identification produces meaning and power. In the identification process, an object projects the desire to identify and uses identifiers to match the identified subject. The subject either fails or passes the identification. The result of identification often lies in power rather than the nature of the subject because sovereignty reigns in the object-subject relationship. For instance, the rhetoric or the physical form of “Asian woman” is nobody, nameless, classless, faceless, but an identifier in some context, and it only identifies an identifiable subject. To become identifiable, a subject cannot be a free individual but a collectible element; it cannot be a living artwork but a frameable artifact. It must become a narrative.

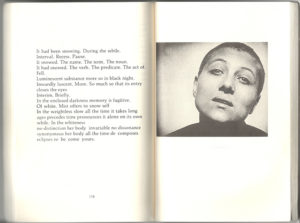

The Korean American artist Theresa Cha provides an antidote to this process with her book, Dictée, and other video works, which became canonical for Asian American art history and attracted a substantial amount of scholarly attention. Many scholars reiterate the dis-identificatory quality of Cha’s works and life. For example, Anne Anlin Cheng insightfully remarks that Dictée is not a reliable source of information with multiple voices, borrowed citations, untranslated French, and captionless photographs. Although the pseudo-autobiography tends to suggest that Cha is a heroine, a post-colonial immigrant that attempts to claim the historical heritage, this heritage simultaneously abandons her as imaginary and discrete[1]. Dictée subverts our clinging onto authorship, collective memory, and martyr narrative while revealing the contingency of identification – Dictée is dis-identificatory, rejecting the identifications created and sustained by power.

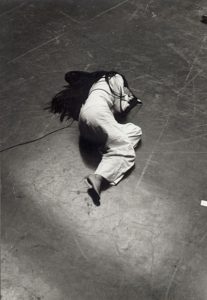

Cha’s life is another example of disidentification. In Dictée, Cha implies the traumatic story of her mother rather than herself. In Permutations, a video work where she displays the portrait stills of her sister, the image discloses while forecloses any close reading of an identity that is not even hers. Cha’s portrait only flashes between her sister’s stills. Resuscitated almost like an Asian female martyr, her identity is another traumatic story that few scholars dared to elaborate on. Cathy Park Hong reveals the unexamined aspect of Cha’s life[2]. While Cha was ghastly raped and murdered at the age of 31, her death was only covered by a newspaper obituary and ironically ignored by the ensuing fanfare of her art. Dictée is an ironic prophecy of Cha’s life and afterlife as dis-identificatory, while unintended.

Cathy recognizes Cha’s legacy as she tells Cha’s story in a highly personal and dialogical tone. To tell a story of an individual about her struggles, childhood, family, and death is a rebellion against the identificatory mechanism that only identifies what it prefigures to identify, thus identification itself to form a self-deceptive narrative not about her, but the desiring objects. Cathy never attempts to speak in the voice of Cha, but of herself, to speak to Cha, instead of speaking as Cha. In this dialogue, Cha speaks to us freed from an identificatory narrative while echoes Anne Anlin Cheng’s reading of “I” as breaking through the boundary between reading and experiencing history. In Cathy’s account of when Cha’s brother John and her mother received Dictée and recognized Cha’s voice through the seemingly arcane fragments, the identification breaks down on the tenuous cusp between self and others, thus acquiring a new identity only sensible to Cha’s family.

Disidentification recycles and rethinks embodied meaning. Dictée scrambles the original meaning of Cha’s given identity and suggests a queer reading of Cha, her book, and the cultures, the multivocal complex of aesthetics and politics. José Esteban Muñoz makes a compelling statement about this type of disidentification art: “disidentification is a step further than cracking open the code of the majority; it proceeds to use this code as raw material for representing a disempowered politics or positionality that has been rendered unthinkable by the dominant culture[3].” In Dictée, Cha recites the basic instructions of the naturalization process and forms an internal critique against it by situating within and without the political discourse through which she is called to identify. She writes: “Documents, proof, evidence, photograph, signature. One day you raise the right hand, and you are American[4].” Hereby, identity politics and nationalist narratives are rendered artificial and questionable in Cha’s rethinking and recycling of their rhetoric and physical forms.

It is noteworthy that visual disidentification operates contingently and affects ephemerally. Judith Butler questions the further implications of this queer practice: “What are the possibilities of politicizing disidentification, this experience of misrecognition, this uneasy sense of standing under a sign to which one does and does not belong[5]?” If disidentification effectively knocks open many closets of our society, it should keep knocking on them if the doors close again. To constantly guarantee this process, an extensive queer visual culture should be established, and contemporary art plays an indispensable role in providing the identifiers of political disidentification. The practical questions emerge: who are the active providers and what are the identifiers?

Contemporary artists show the possibilities of political disidentification. In What is Contemporary Art?, Terry Smith points out the three currents of global contemporary art, and the third is a generational change that features a shifting tendency towards connectivity, immediacy, and ephemerality – the fluidity of everyday life. The new generation makes visible our sense that the fundamental, familiar constituents of the being are becoming steadily stranger, while “contemporary” as “con-tempus” implies a multiplicity of relationships between being and time[6]. Questioning the singular while accepting the plural sets the foundation for producing dis-identificatory art. In Dictée, Cha writes, “martyrdom was the dream of my youth, and this dream has grown with me with Carmel’s cloisters. But here again, I feel that my dream is a folly, for I cannot confine myself to desire one kind of martyrdom. To satisfy me. I need all[7].” This pseudo-confession demonstrates a similar drive to pluralize an ideology, a desire, and an image, which parallels the practices of artists like Monyee Chau.

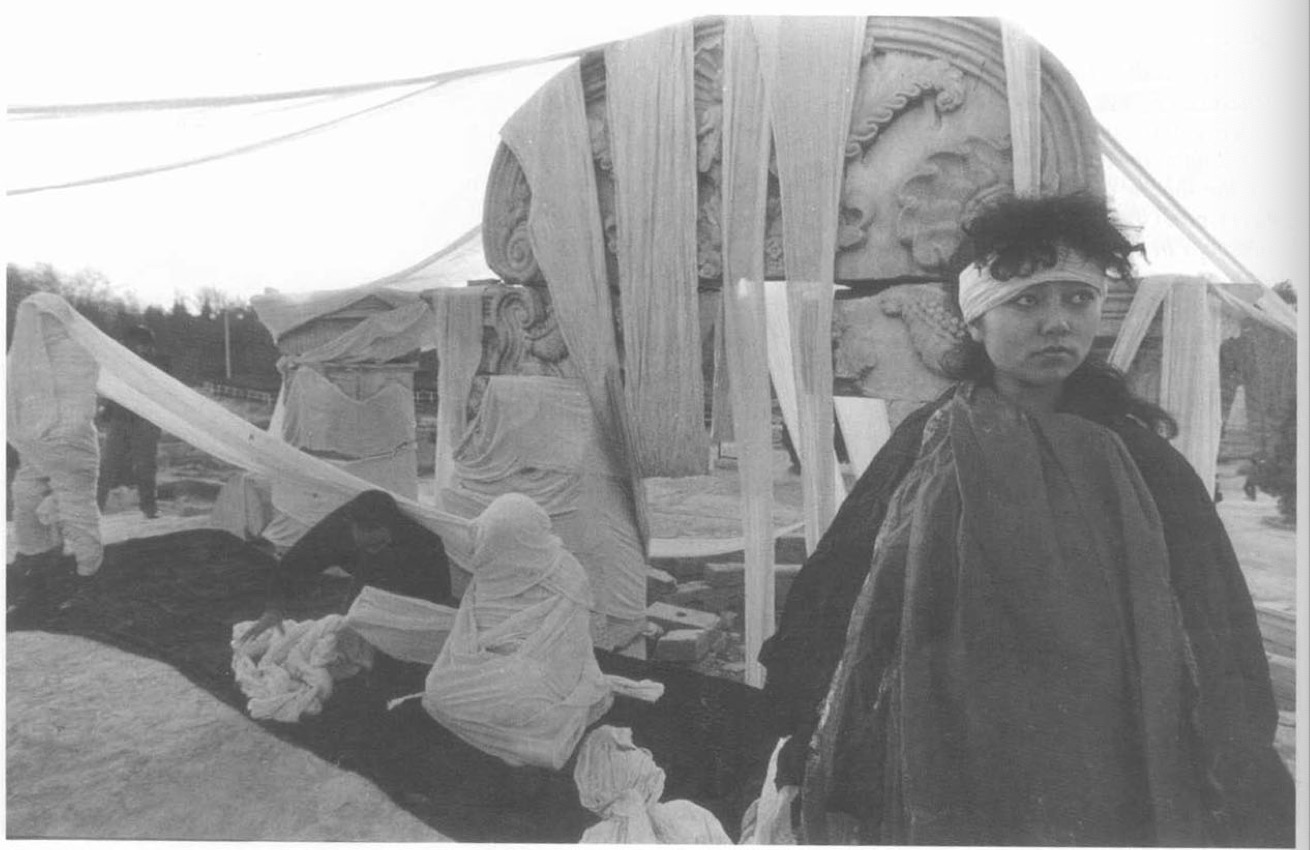

Chau demonstrates strength in using the familiar identifiers to dis-identify the fluid everyday life she belongs to and does not belong to. In an installation entitled The Things They Carried, Chau composes a living room filled with the found objects her family brought as immigrants, including a suitcase they brought from Hong Kong, which contains clothes, paperwork, film of her family in front of the first house they bought in Seattle, fabric her was wrapped in as a child, and cloth they used to separate their studio apartment for their 4-person family. Although the space models after Chau’s living room, the prominent location of the incense reminds its nebulous function as an ancestral shrine. Other highlights are the IKEA-style carpet and the golden paper ingots casually scattered on the carpet, enshrouded by the canary lighting, which emphasizes the centrality of the worship tablets, the unsettling red of the hanging cloth, and the yellow paint of the side walls. The entire space suggests a narrative that it is simultaneously rejecting. A coherent identity is constantly disrupted by the color scheme, “incompatible” objects, and the lack of visual hermeneutics. Monyee Chau estranges the fundamental identifiers abused to identify a Chinese immigrant by recycling and rethinking their embodied meanings. Like Cha’s Dictée, The Things They Carried is an effective rebellion against the documentary impulse underlying the ethnic and post-colonial building[8]. However, this work also suggests another homecoming that is only comprehensible through disidentification, just like the ambiguous exposure of Chau’s baby wrap.

Cha’s legacy flows beyond Asian American art. With the burgeoning of queer art, which emphasizes the disidentification of gender, ideology, ethnicity, and more, Dictée continues to inspire new forms. For its readers, this unique book is both unifying and personal. Rereading Dictée feels like an internal journey to examine other possibilities of oneself with a unique voice softly whispers: “when these possibilities are free, art will be free.”

— Written by Moham Wang

Bio:

Moham Wang is a graduate student of Critical Studies: Aesthetics and Politics at California Instutute of the Arts. He’s a curator, artist and writer of lu Mien ethncity. Wang’s works can be found in Aesthetic Education, a national art journal in Asia.

[1] Anne Anlin Cheng, “Memory and Anti-Documentary Desire in Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictée,” MELUS 23, No. 4 (1998): 119, accessed December 8, 2017, http://www.jstor.org/stable/467831.

[2] Cathy Park Hong, “Portrait of An Artist,” in Minor Feelings (New York: One World, 2020), 155.

[3] José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis, MN: U of Minnesota P, 1999), 50.

[4] Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, “Caliope Epic Poetry,” in Dictée (Los Angeles, Berkeley, London: University of California Press, 1982), 56.

[5] Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (New York: Routledge, 1993), 61.

[6] Terry Smith, introduction to What is Contemporary Art? (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2009), VIII.

[7] Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, “Erato Love Poetry,” in Dictée (Los Angeles, Berkeley, London: University of California Press, 1982), 117.

[8] Anne Anlin Cheng, “Memory and Anti-Documentary Desire in Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictée,” MELUS 23, No. 4 (1998): 123, accessed December 8, 2017, http://www.jstor.org/stable/467831.