OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

The War Machine Wears a Veil: A Lecture on Martial Aesthetics by Anders Engberg-Pedersen

Photo courtesy of Ish

We’re driving down the 5 freeway at dusk after Anders Engberg-Pedersen’s lecture in Butler.

His literary anchor throughout the presentation was the 2015 techno-thriller Ghost Fleet by authors P.W. Singer and August Cole. The book’s byline read: “A Novel of the Next World War” in all caps as if to compensate for its fictitious nature that it is certain that these 416 pages are a glimpse into a predictive future. The thing is, this claim might not be totally false.

The four of us are digesting the lecture as I bypass the 210 East interchange. We’re talking about war, martial aesthetics specifically, and at some point in our conversation Ish says, “But Deleuze’s thing about the war machine is that it’s always just battles of territorializing, and all it does is just feed the war machine. What kept like, echoing in my mind: people do talk and they talk within their territories and they’re trying to fight over their territories or move things from different territories. But at the end of the day, like, it actually does no impact on the real, like actual real, world.”

I want to believe that there’s no impact on the real world, I do. In the Deleuzian war machine, the state is aware that this sort of originary and ongoing entity of war exists. The state also understands that in order for it to preserve its sovereignty, it must utilize the tools of the machine at its disposal to employ a prophetic future. Therefore, the war machine is used as logic for the state’s means and ends (but really, no end, since this is an infinite cycle). The kind of territory assigned in this situation would be that of the creatives tasked with the aestheticization of war.

Maisa finds it so odd that us, a car full of artists, have never really heard of this niche realm of narrative and aesthetic practices. It hasn’t crossed over into our kind of Deleuzian territory. Engberg-Pedersen has introduced this eclipse for us: literature of the militarization persuasion can be dated back to as early as 1793, The Reign of George VI 1900-1925, under the genre of military science fiction, a sort of “history of what’s to come.” This realm has been here for quite some time, it’s just rarely ever introduced into the territory we’re familiar with.

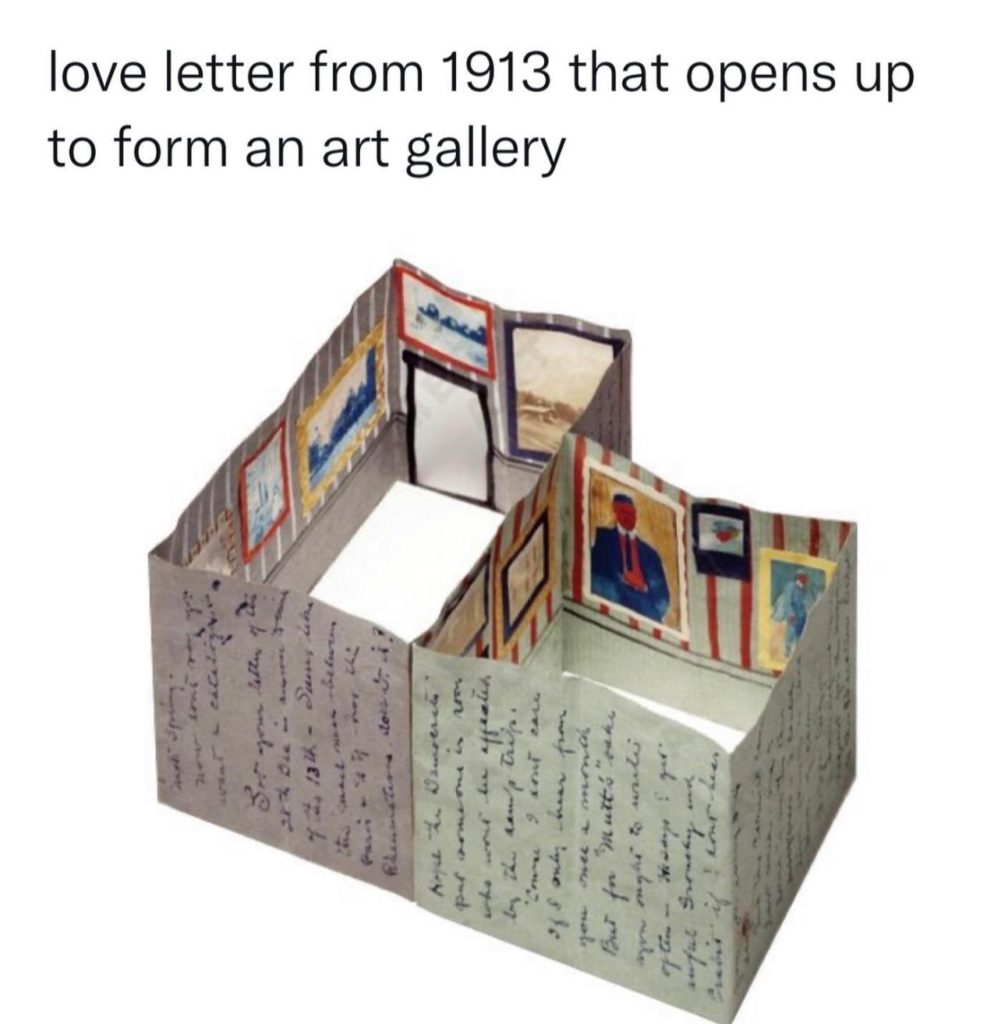

Photo courtesy of archive.org

After a quick Google search, I find that 5 years following Ghost Fleet arrives Burn-In, another techno-thriller by duo Singer and Cole. Former director of the CIA General David Petraeus praises the authors as “scientifically grounded futurists,” confirming alongside a number of other military officials the accuracy of this work of fiction. These two novels are what is called “useful fiction” under the genre of the national security novel. Not far from an unimaginable storyline, this kind of storytelling is an amalgamation of research analysis and fictitious situations, Engberg-Pedersen reveals, where former military officers and affiliates with the FBI and CIA have tried their hand at the pen. The veil between reality and fiction here is purposefully thin, almost translucent. To very loosely channel Žižek working with Nietzsche, the veil conceals the ultimate Truth, and so the veil must remain because of this hidden threat.

If you’re picking up what Engberg-Pedersen is laying down, then you’re right here with us in the car.

The ultimate goal of these types of novels is to present the ideal situation of war calculated precisely by design in such a way that allows the reader to situate themselves in the given scenario. In recent years, the novels have spanned a shorter timeline: the authors give us an idea of what to expect for the next 10-15 years instead of the older models that were either reflective (a history of its own design), or depicted multiple decades into the future.

The present that you and I are living in now has a literal countdown clock backed by climate scientists. Mimesis of a finite future provides security for the reader, envisioning a possible conflict and assuming solution where the sovereign country prevails, of course. A baseline level of anxiety and depression is a frequent common denominator amongst most of the US population, so it would appear as a relief to receive a “blueprint for the wars of the future,” as Retired Admiral James Stavridis claims Ghost Fleet to be. Engberg-Pedersen’s lecture describes the envisioning aesthetic as an operative of knowing, as model. This is where I want to believe Ish when she says it has no impact on the real world.