OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

The Tide Line

I spent my childhood on Santa Monica’s public beaches, congregating with Angelenos from far and wide as we sought respite from the summer heat. I skipped through numbingly cold waves, burrowed in the hot sand, built sloppy castles, caught and released sand crabs, fell off my surfboard, and succumbed to the will of the water that would toss me around like a rag doll.

Along California’s coast and across the country, real estate speculation, privatization, and ecocide threaten public access to beaches as sites of communion, recreation, rest, and learning. Though the California Coastal Act upholds universal access for beaches below the median high tide line, private ownership of sands above this threshold often limits access to the ocean.1 As of 2003, 58% of the California shoreline was owned privately or held by governmental entities (mainly the military) that prohibit public access.2 The encroachment of the private realm onto public beaches is further exacerbated by the threat of rising sea levels, as research estimates suggest that 24 to 75% of the state’s beaches could completely erode by the end of the century.3

In a talk at the Roy and Edna Disney CalArts Theater (REDCAT) in February of this year, Macarena Gómez-Barris spoke of her childhood experiences at Zuma Beach. About twenty miles north of Santa Monica Beach as the crow flies, Zuma welcomes a diverse influx of visitors from across Los Angeles in contrast with the increasingly privatized, inaccessible, and unwelcoming beaches of affluent Malibu. Titled “Decolonial Queer Fem Thought and Praxis,” Gómez-Barris’s presentation was the first installment of the “Ecofeminisms: Practices of Survivance Series,” organized by Janet Sarbanes for the spring 2025 Aesthetics & Politics Lecture Series at CalArts. In her articulation of colonial extractivism and encroaching privatization, Gómez-Barris juxtaposed Indigenous, queer, and feminist engagements with the ocean against violent and rigid notions of property associated with late imperial land possession. Such engagements think through the aquatic, fluid, and submersive to realize the generative capacity of the space between land and sea. In her focus on the sea’s edge, Gómez-Barris emphasized the power in choosing amorphous and porous borderline sites that transcend false binaries.

While my upbringing in Santa Monica was characterized by countless beach days, many children just 15 miles inland have never touched the ocean.4 Despite its reputation as a steadfast public fixture, Santa Monica Beach is littered with legacies of colonial domination, extractive capitalism, and racial exclusion that continue to leave traces scattered across the coastline. Though these vestiges evade easy identification as a result of the systematic erasures that presuppose them, visual clues still adorn beachside spaces – often in the form of signage.

Advertisements and traffic signage saturate the entrance to the Santa Monica Pier.

“The Inkwell”

Before Spanish settlers gave Santa Monica its name in an act of violent erasure, indigenous Tongva and Chumash communities had stewarded the seaside land for thousands of years.5 As Santa Monica’s population grew in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the fishing village and its adjacent industry attracted Japanese, Latine, and Black newcomers – especially as economic instability in Mexico and racism in the Jim Crow South spurred mass migrations.6 Because real estate redlining excluded Black and Brown people from living in much of Santa Monica, the Belmar, Ocean Park, and Pico neighborhoods became relatively self-sufficient multiethnic enclaves fit with small businesses and churches.7

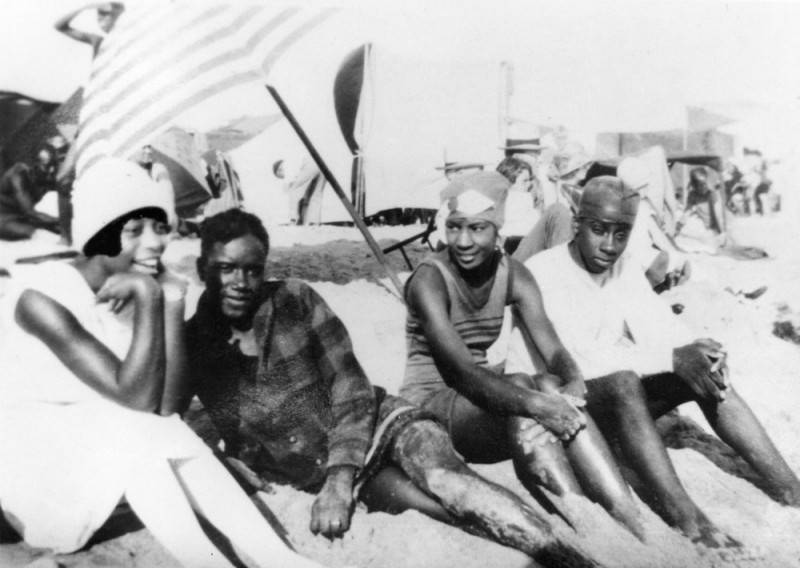

Despite providing the service and manufacturing labor foundational to Santa Monica’s economic growth and stability, these communities were largely excluded from nearby beaches. Santa Monica Beach was effectively segregated from the 1910s through the 1960s, even after codified racial exclusion on beaches was abandoned in 1927.8 A two-block stretch of sand between Bicknell Street and Pico Boulevard, known as “Bay Street Beach,” welcomed Black people seeking refuge from harassment across the remainder of the city’s 3.5 miles of shoreline.9 This area was derogatorily nicknamed “the Inkwell.”10 In the 1940s, the first documented surfer of African American and Mexican descent, Nick Gabaldón, would paddle all the way from Bay Street Beach to Malibu to access better waves without setting foot on hostile white beaches.11

Group at Santa Monica Beach, 1926, Shades of L.A. Collection, Los Angeles Public Library.

The memorial plaque for Bay Street Beach.

Though Black and Brown people were overwhelmingly relegated to service jobs in the early 20th century (and even those with higher education, like teachers, were often barred from qualified employment), many started small businesses throughout Santa Monica.12 While the city’s tourism industry relied on its beaches and businesses catering to beach goers, white residents and politicians aggressively stymied Black commerce and recreation along the shore.13 The Santa Monica Bay Protective League, which was “opposed to negroes encroaching upon the city” and sought to safeguard their property values from “menaces,” organized effective opposition to numerous Black businesses.14 In the 1920s, they lobbied Santa Monica officials to shutter the doors of a dance hall on Third Street and helped pass an ordinance that halted the development of a Black resort at Bay Street Beach by limiting new construction to single-family homes.15 Just two years later, the city council sidestepped this ordinance to allow white investors to construct an exclusive and hostile white beach club, Casa del Mar, on the same land.16

A sign reading “Bay Street Beach Historic District” points towards the Casa Del Mar hotel.

This pattern echoed across the California coast, where white residents feigned concern for the preservation of public beaches to deter Black and Brown people from establishing oceanfront businesses and community spaces.17 When their political power failed to halt such projects, like Huntington Beach’s Pacific Beach Club, white arsonists took matters into their own hands.18 Meanwhile, private white beaches were spared from this passionate battle for public space, as the shoreline became the site of concentrated wealth accumulation for whites. For example, two off-duty sheriffs shot a Black man passing through a private beach near Topanga Canyon on Memorial Day in 1920.19 Despite their oppositional relationship, the constructs of “public” and “private” have both been weaponized to uphold white spatial and economic supremacy along the coastline.

Despite these attacks, Black Santa Monicans persisted in their claim to Bay Street Beach as a site of recreation, play, communion, and resistance. After the exclusive Casa del Mar was constructed, beach goers would dance to the live music wafting from inside and capitalize on its bright lights for night swims.20 Gabaldón took to the ocean to bypass racial exclusions on land, choosing the aquatic as a space of freer mobility.21 While Bay Street Beach was enclosed by a private white club to the east and sandwiched between “public” white beaches to the north and south, the Pacific Ocean to the west formed a more fluid margin. As Gómez-Barris’s work suggests, the porosity of the sea’s edge serves as a counterpoint to the violent rigidity of society’s racial borderlines.

A police unit patrols Bay Street Beach, passing by a lifeguard tower with posted rules: “No Alcohol, No Smoking, No Dogs or Cats, No Overnight Sleeping or Camping, No Fireworks, No Fires, No Soliciting or Selling Merchandise, Permit Required for Events/Activities, No Drones, No Motorized Scooters/Bikes, Parking Lots are for Parking Only, No Disturbances.” A person rests in a sleeping bag below the tower.

A wooden boardwalk juts into the sand at Bay Street, the original social focal point of Bay Street Beach.

Erasing Santa Monica

When World War II wound to an end, urban planners began to fret about rapid population growth, the decline of wartime employment, and urban disorder.22 Across the United States, federal, state, and local governments deployed “blight” removal and urban renewal projects to displace and segregate Black, Latine, Asian, immigrant, and poor people.23 In Los Angeles, freeways became an effective tool to enact racial segregation through the demolition of communities and the facilitation of sprawling white suburbia.24 During this period, Santa Monica’s civic leadership adopted a pro-development mindset that would last for decades.25 Like urban renewal projects in greater Los Angeles and across the country, many of these developments for “the public” would conveniently skirt around white communities to target Black and Latine residences and businesses.

In 1957, the Black neighborhood of Belmar was selected for the site of the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, displacing residents remaining from the 1930s expansion of Santa Monica High School.26 The following year, right-of-way acquisitions began for the Santa Monica Freeway.27 The government weaponized eminent domain to barrel through the most racially integrated (Black, Latine, Asian, and white) and affordable district in Santa Monica: the Pico Neighborhood.28 Between 600 and 1500 Black and Latine families who had lived there for an average of 17 years were displaced.29 Still legally excluded from buying or renting in most of Santa Monica before the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1964,30 many of these families were displaced out of the beachside city altogether. Between 1970 and 1980, Pico Neighborhood’s Black population declined by 30%.31 Today, there are fewer Black families living in Santa Monica than in 1960, despite overall population growth.32

The displacement and dispossession of Black and Brown Santa Monicans did not come to an end with the Civil Rights Movement. Instead, more covert methods were deployed to target poor and working-class families (whose economic conditions were, of course, shaped by the aforementioned decades of overt racism). Deindustrialization minimized job opportunities as industrial employers that had previously spurred Santa Monica’s diverse population growth, like Douglas Aircraft, left the city.33 Progressive housing attitudes of the 1970s came to a screeching halt with the passage of the Costa Hawkins Housing Act in 1995, which deregulated vacancy control and disincentivized landlords from participating in Section 8.34 Over the next two decades, many left Santa Monica searching for more affordable housing.

Today, gentrification continues to reproduce demographic erasures in Santa Monica as luxury housing, office buildings, high-end grocery stores, and upscale restaurants replace existing residences and businesses. Median household income increased from $50,714 in 2000 to $109,739 in 2023, and houses now sell for an average of $1.7 million.35 Proximity to the ocean is a luxury amenity, with homes near Bay Street Beach listed between $2 and $4 million on Zillow.36 Today, Santa Monica’s Black population dwindles at less than 5%, Asians at 10%, and Latines/Hispanics at 16%.37 Whites take the majority at 61%.38 As the city fights to maintain its image as a resort town and tourist destination, erasures continue in the form of eugenic anti-homeless policies that seek to push the visual evidence of poverty off public beaches and out of Santa Monica city limits, while failing to resolve housing deprivation (which disproportionately impacts Black people). 39

Luxury beachfront apartment buildings advertise along the bike path.

No trespassing signage guards a secured luxury hotel property along Santa Monica Beach.

Public and Private…

Santa Monica Beach is no longer segregated and now serves as a beacon of public recreation along California’s increasingly privatized and inaccessible coastline. Yet, the city’s patterned foreclosure of Black and Brown placemaking and economic mobility laid the foundations for a lasting hegemony at the sea’s edge.

Generations of families displaced from Santa Monica now travel for miles to access public beaches. For the working class, making it to Santa Monica Beach from inland parts of the city is a trek that not all can afford. Though public transportation was recently improved with the addition of the Metro Expo Line through Santa Monica, it is still insufficiently connected to much of Los Angeles County. Those who can afford leisurely car expeditions across the sprawling metropolis on a summer weekend are welcomed by limited and expensive amenities (like parking), packed beaches, and polluted waters.

Parking signage and pay booths/machines saturate Santa Monica’s public beaches.

A cafe sign warns, “Credit cards required for boardwalk seating.”

With inaccessibility seeping across California’s coastline, beaches that remain public are overwhelmed by visitors in peak seasons. Even on public beaches, the pursuit of private profit reigns supreme. From the casino barges of the early 20th century to the adjacent resorts, hotels, restaurants, and stores of today, the natural attraction of the coastline is commodified for economic growth.40

Tourist information touch displays cycle through corporate advertisements while municipal signage prohibits street vending.

Santa Monica Beach’s most iconic destination, the pier, exemplifies the overlap between public and private at the sea’s edge. Originally constructed in 1909 to support a sewage pipeline into the ocean, the pier now provides a bustling recreational space to those who can afford its overpriced attractions.41 Though owned by the City of Santa Monica and presented as a public recreational amenity fit with its own police station and plastered with municipal codes, large swaths of the pier (like the amusement park) are privately owned by businesses and corporations that reap profound profits from this public space. Meanwhile, vending is strictly controlled on the pier, with authorized vendors holding prime real estate and the rest vying for leftover spaces a safe distance away from its surrounding “no vending” bubble.

Santa Monica Pier bustles with visitors, fishermen, permitted vendors, and amusement park goers.

A sign discourages visitors from buying from unpermitted vendors.

Surveillance infrastructure on the Santa Monica Pier protects private businesses.

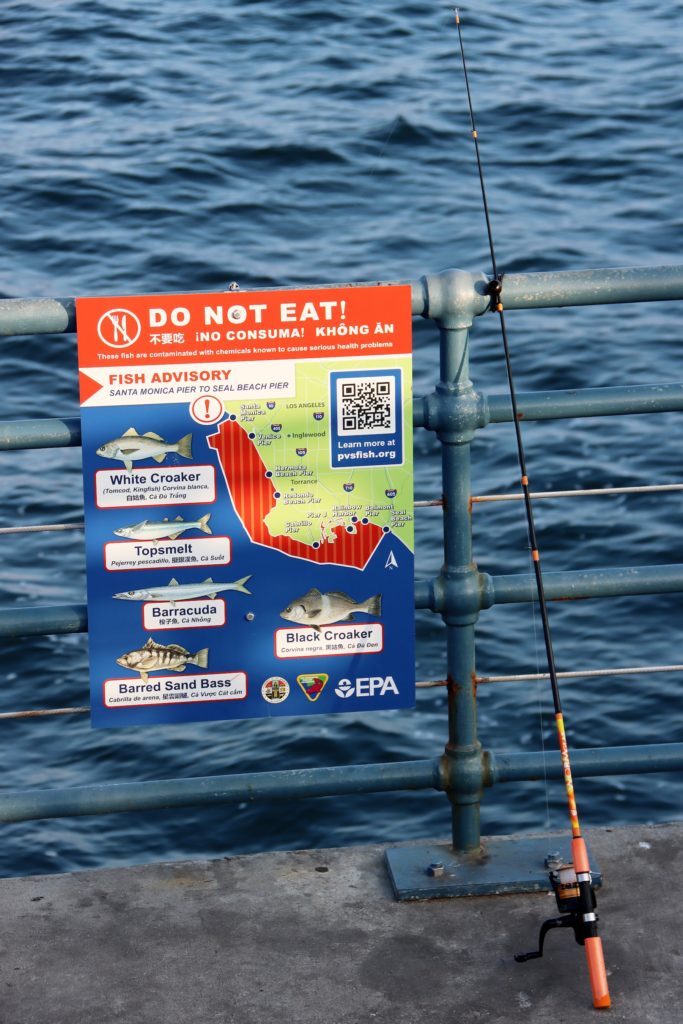

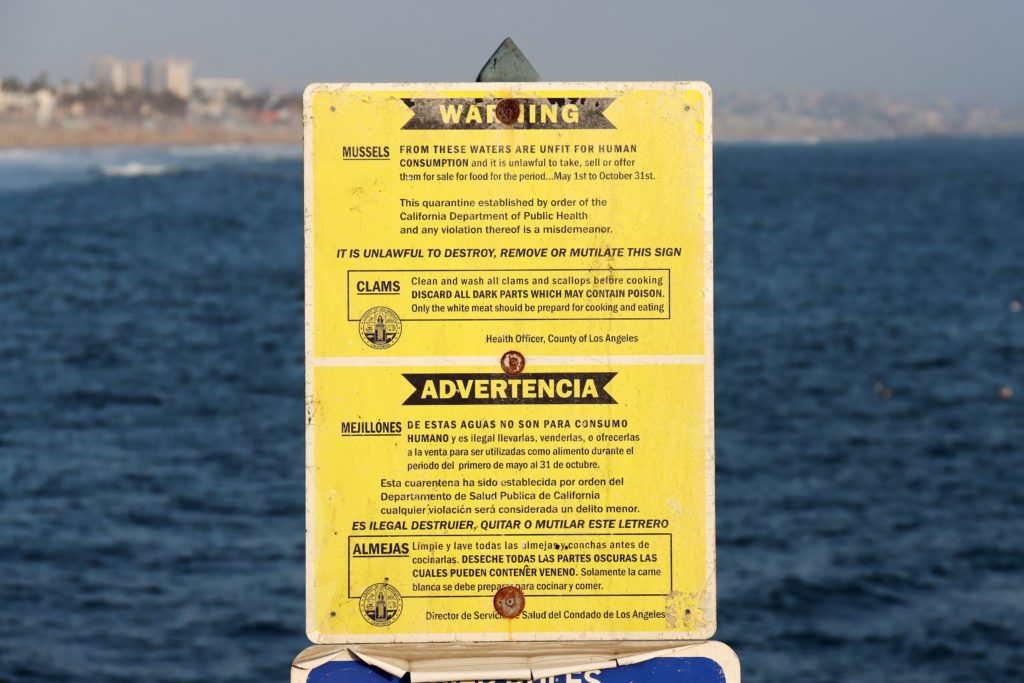

The pier’s harmful ecological footprint further illuminates the legacy of colonial domination in Santa Monica. According to Heal the Bay, its adjacent beaches ranked as having the third-dirtiest water quality along the West Coast.42 Exacerbated by other negligent environmental practices in the city, high bacterial levels routinely put swimmers and wildlife at risk. Fishermen still take to the perimeters of the pier, but posted signage warns that many sea critters are contaminated and not safe for consumption. In endangering both human and non-human organisms, the pier’s environmental impact further problematizes the accessibility of Santa Monica Beach.

Though it is relished by residents and tourists alike, the Santa Monica Pier embodies the encroachment of capital accumulation onto the public waters enjoyed most by those who are denied access to luxury private beaches. This encroachment ties the domination of ecocide with the domination of racial capitalism as they converge on the coastline.

A sign warns fishermen not to consume certain fish that are “contaminated with chemicals known to cause serious health problems.”

A sign warns that mussels in the water below are unfit for human consumption and that clams and scallops should be cleansed of “all dark parts which may contain poison.”

… Are Both Property

In 2018, a major win for public beaches was secured when the Supreme Court refused to hear a challenge to the Coastal Act brought by a billionaire venture capitalist as he fought to prevent public beach access via a private roadway.43 Today, the public’s fight against privatization continues to dominate narratives about equitable beaches.

However, the amorphous nature of the tide itself complicates the distinction between public and private. The mean high tide line is used to safeguard public access to the ocean, but its boundaries shift with the change of seasons and geological conditions, such as erosion.44 Gómez-Barris’s use of the sea’s elusive edge to think through the tidal, the fluid, and the aquatic speaks to the constraints of rigid colonial schema in defining space. The tension between public and private reflected in legal battles, where the public is framed as a democratic good and the private as a neoliberal evil, falls short in accounting for the historical forces underlying this dialectic.

Private property signage on the public pier.

No trespassing signage on the pier.

The mobilization of “the public” towards racial and class domination complicates its purported egalitarian character. In the 20th century, civic infrastructure was deployed to ethnically cleanse Santa Monica, and advocacy for “public” beaches doubled as the sabotage of Black businesses. Today, the protection of public space conceals attempts to criminalize poverty across the city’s parks, sidewalks, and beaches. When the “general will” refers to the will of the powerful, civic projects harm facets of society, and publicly-owned spaces are not accessible to all, the very constitution of “the public” seems exclusive at best.

Private shops on the public pier welcome paying customers with decals from Santa Monica Travel & Tourism.

A sign lists prohibited activities in public restrooms, which the city locks every night.

While the hierarchical dualism of human versus nonhuman greenlights environmental destruction, the binary of the public versus the private is also weaponized by the powerful to dominate urban and natural spaces. As two sides of the same coin, these mutually sustaining constructs rely on each other to reinforce the logics of property and ownership.

Closing

The start of 2025 has brought further challenges to Santa Monica Beach. Recent firestorms polluted the sand and water with toxic debris, and dead sea mammals are washing ashore due to algal bloom exacerbated by run-off.45 As long as capitalism and imperialism reign supreme over Indigenous knowledge and environmental science, the climate catastrophe will continue to amplify existing racial, class, and ecological inequities along the coastline.

Even so, sea edges continue to serve as spaces of potentiality and resilience.46 The tideline refuses the fixed binary of public property versus private property, whose tension reflects a logic of possession incompatible with the character of water. More so, it may reveal the weaknesses of activisms limited by the parameters of lawful ownership. Though useful in immediate environmental preservation and public accessibility, reformist approaches will likely prove futile in addressing the racial capitalism and settler colonial extractivism that preclude equitable and sustainable futures. In its formidable fluidity, the ocean itself models practices of survivance better equipped to overcome constraints of the current moment.

Seawater surrounds the pier’s metal pillars, which mussels have transformed into habitats.

Tara Edwards is an art educator interested in urban infrastructure, critical geography, and graffiti.

Footnotes

- Jeremy Rosenberg, “Why California’s Beaches are Open to Everyone,” PBS SoCal, June 25, 2012. ↩︎

- Beachapedia, “State of the Beach/State Reports/CA/Beach Access,” accessed April 9, 2025. ↩︎

- Coastal and Marine Hazards and Resources Program, “New Research Reveals Alarming Future for California’s Coastline,” U.S. Geological Survey, June 8, 2023. ↩︎

- Eun Kyung Kim, “Surf Bus Connects Inner-City Youth with the Ocean,” Today, June 21, 2014. ↩︎

- Susan Suntree, interview in Santa Monica 90404 (aka 90404 Changing), directed by Michael Barnard (Vimeo, February 1, 2018), accessed March 11, 2025. ↩︎

- Deirdre Pfeiffer, The Dynamics of Multiracial Integration: A Case Study of the Pico Neighborhood in Santa Monica, CA (Master’s thesis, Arizona State University, January 2007), 27-33. ↩︎

- Hadley Meares, “How Racism Ruined Black Santa Monica,” LAist, December 23, 2020. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Alison Rose Jefferson, Reconstruction and Reclamation: The Erased African American Experience in Santa Monica’s History, (Santa Monica: Belmar History + Art, 2020). ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Meares, “How Racism Ruined Black Santa Monica.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Jefferson, Reconstruction and Reclamation. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Meares, “How Racism Ruined Black Santa Monica.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Martin J. Schiesl, “City Planning and the Federal Government in World War II: The Los Angeles Experience,” California History 59, no. 2 (Summer 1980): 126–143. ↩︎

- Mindy Thompson Fullilove, Root Shock: How Tearing up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It, New Village Press ed. (New York: New Village Press, 2016). ↩︎

- Jeremiah Axelrod, Inventing Autopia: Dreams and Visions of the Modern Metropolis in Jazz Age Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009). ↩︎

- Jefferson, Reconstruction and Reclamation. ↩︎

- Nathan Masters, “Creating the Santa Monica Freeway,” PBS SoCal, September 9, 2012. ↩︎

- Jefferson, Reconstruction and Reclamation. ↩︎

- Pfeiffer, The Dynamics of Multiracial Integration. ↩︎

- Squier and Landecker and Capek and Gilderbloom, as cited in Pfeiffer, 39. ↩︎

- Pfeiffer, The Dynamics of Multiracial Integration, 45. ↩︎

- Ibid, 42. ↩︎

- Aaron Schrank, “Santa Monica Tries to Repay Historically Displaced Families,” KCRW, January 31, 2022. ↩︎

- Pfeiffer, The Dynamics of Multiracial Integration, 42, 51. ↩︎

- Ibid, 43, 127. ↩︎

- City-Data.com, “Income in Santa Monica, California,” accessed April 12, 2025.

Zillow. Santa Monica, CA Housing Market: 2025 Home Prices & Trends. Accessed April 9, 2025. ↩︎ - Ibid. ↩︎

- U.S. Census Bureau, QuickFacts: Santa Monica City, California, Accessed March 11, 2025. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Homelessness in Los Angeles County 2024,” LA Almanac, accessed April 16, 2025. ↩︎

- Andrew W. Kahrl, The Land Was Ours: How Black Beaches Became White Wealth in the Coastal South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012).

Santa Monica Pier Corporation, “History,” Santa Monica Pier, accessed April 12, 2025. ↩︎ - Ibid. ↩︎

- Heal the Bay, “Beach Report Card 2023–2024,” 2024. ↩︎

- Mat Arney, “Locals Only? California’s Beach Access For All, Not Just The Affluent,” Surf Simply Magazine, accessed April 9, 2025. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Jillian Marshall and Annelisa Moe, “Ash to Action: Heal the Bay’s Post-Fire Water Quality Investigation,” Heal the Bay, March 25, 2025. ↩︎

- Macarena Gómez-Barris, “Life Otherwise at the Sea’s Edge,” Open Rivers: Rethinking Water, Place & Community, no. 13 (2019). ↩︎

Bibliography

Agamben, Giorgio. “What is a People?” In Means Without End: Notes on Politics, translated by Vincenzo Binetti and Cesare Casarino, 39-46. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

ArcGIS StoryMaps. “Who owns the beach?” Accessed April 9, 2025. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/ec34e95df374411b8ad77256fa7f722d.

Arney, Mat. “Locals Only? California’s Beach Access For All, Not Just The Affluent.” Surf Simply Magazine, accessed April 9, 2025. https://surfsimply.com/magazine/locals-only-californias-beach-access-for-all-not-just-the-affluent.

Axelrod, Jeremiah. Inventing Autopia: Dreams and Visions of the Modern Metropolis in Jazz Age Los Angeles. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Barnard, Michael, dir. Santa Monica 90404 (aka 90404 Changing). Vimeo. February 1, 2018. Accessed March 11, 2025.

Beachapedia. “State of the Beach/State Reports/CA/Beach Access.” Accessed April 9, 2025. https://beachapedia.org/State_of_the_Beach/State_Reports/CA/Beach_Access.

Blain, Keisha N. “Free the Beaches: A New Book on the Fight for Racial Equality in Connecticut.” African American Intellectual History Society, April 14, 2018. https://www.aaihs.org/free-the-beaches-a-new-book-on-the-fight-for-racial-equality-in-connecticut/.

Brodsly, David. L.A. Freeway, an Appreciative Essay. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981.

Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2004).

California Beaches. “See the Beaches on Santa Monica Bay.” Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.californiabeaches.com/map/las-beaches-santa-monica-bay/.

California Coastal Commission. YourCoast Map. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.coastal.ca.gov/YourCoast/#/map.

City-Data.com. “Income in Santa Monica, California.” Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.city-data.com/income/income-Santa-Monica-California.html.

Coastal and Marine Hazards and Resources Program. “New Research Reveals Alarming Future for California’s Coastline.” U.S. Geological Survey, June 8, 2023. https://www.usgs.gov/programs/cmhrp/news/new-research-reveals-alarming-future-californias-coastline.

“Freeway Pact Wins Santa Monica OK: 2 Changes Asked by Bay City.” Los Angeles Times, Jan. 31, 1960.

Fullilove, Mindy Thompson. Root Shock: How Tearing up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It. New Village Press edition, [second edition]. New York: New Village Press, 2016.

Gadsden, Brett. “Race, Capitalism, and the Rise and Fall of Black Beach Communities.” Southern Spaces, March 11, 2014. https://southernspaces.org/2014/race-capitalism-and-rise-and-fall-black-beach-communities/.

Gómez-Barris, Macarena. “Life Otherwise at the Sea’s Edge.” Open Rivers: Rethinking Water, Place & Community, no. 13 (2019). https://openrivers.lib.umn.edu/article/life-otherwise-at-the-seas-edge/

Heal the Bay. “Beach Report Card 2023–2024.” 2024. https://healthebay.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Beach-Report-2023-2024_screen.pdf.

Honig, Bonnie. Public Things: Democracy in Disrepair. New York: Fordham University Press, 2017.

Houston, James R. “The Economic Value of America’s Beaches.” Shore & Beach 92, no. 2 (Spring 2024): 33–43.

Jefferson, Alison Rose. “Reconstruction and Reclamation: The Erased African American Experience in Santa Monica’s History.” Santa Monica: Belmar History + Art, 2020.

Kahrl, Andrew W. The Land Was Ours: How Black Beaches Became White Wealth in the Coastal South. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Kent‐Stoll, Peter. “The Racial and Colonial Dimensions of Gentrification.” Sociology Compass 14, no. 11 (2020): e12838.

Kim, Eun Kyung. “Surf Bus Connects Inner-City Youth with the Ocean.” Today. June 21, 2014. https://www.today.com/news/surf-bus-connects-inner-city-youth-ocean-1d79832194.

LA Almanac. “Homelessness in Los Angeles County 2024.” Accessed April 16, 2025. https://www.laalmanac.com/social/so14.php.

Lecher, Colin, and Maddy Farner. “Black and Latino homeless people rank lower on L.A.’s housing priority list.” Los Angeles Times. February 28, 2023. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-02-28/black-latino-homeless-people-housing-priority-list-los-angeles

M.P., Luís. “Public vs. Private Beaches: A Guide to Understanding Access.” SurferToday, accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.surfertoday.com/environment/public-vs-private-beaches-a-guide-to-understanding-access.

Marshall, Jillian, and Annelisa Moe. “Ash to Action: Heal the Bay’s Post-Fire Water Quality Investigation.” Heal the Bay, March 25, 2025. https://healthebay.org/ash-to-action-water-quality/.

Masters, Nathan. “Creating the Santa Monica Freeway.” PBS SoCal, September 9, 2012. https://www.pbssocal.org/shows/departures/creating-the-santa-monica-freeway.

Meares, Hadley. “How Racism Ruined Black Santa Monica.” LAist, December 23, 2020. https://laist.com/news/la-history/black-santa-monica-history-vintage-los-angeles.

Outside in America. “Bussed Out: How America Moves Its Homeless.” The Guardian. December 20, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2017/dec/20/bussed-out-america-moves-homeless-people-country-study.

Pfeiffer, Deirdre. The Dynamics of Multiracial Integration: A Case Study of the Pico Neighborhood in Santa Monica, CA. Master’s thesis, Arizona State University, January 2007.

Quinn Research Center. “The Archive.” Accessed April 9, 2025. https://quinnresearchcenter.com/the-archive/.

Robinson, Cedric J. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983.

Rosenberg, Jeremy, “Why California’s Beaches are Open to Everyone.” PBS SoCal. June 25, 2012. https://www.pbssocal.org/history-society/why-californias-beaches-are-open-to-everyone.

Santa Monica Conservancy. “Santa Monica: A California Dream.” YouTube. August 23, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PIoOb1TRQys.

Santa Monica Pier Corporation. “Our Storied Past.” Santa Monica Pier. Accessed April 12, 2025. https://www.santamonicapier.org/history

Schiesl, Martin J. “City Planning and the Federal Government in World War II: The Los Angeles Experience.” California History 59, no. 2 (Summer 1980): 126-143.

Schrank, Aaron. “Santa Monica Tries to Repay Historically Displaced Families.” KCRW, January 31, 2022. https://www.kcrw.com/news/shows/greater-la/toxins-santa-ana-edu/santa-monica-displaced-black-families-housing.

TIME. “Property Rights: Who Owns the Beaches?” August 29, 1969. https://time.com/archive/6637389/property-rights-who-owns-the-beaches/.

U.S. Census Bureau. “QuickFacts: Santa Monica City, California.” Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/santamonicacitycalifornia/PST045224.

Vartabedian, Ralph. “Decades Later, Closed Military Bases Remain a Toxic Menace.” The New York Times, September 27, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/27/us/military-base-closure-cleanup.html.

White, David. “Addressing Homelessness: Questions and Answers on Santa Monica’s Anti-Camping Ordinance.” Santa Monica Government, September 13, 2024. https://www.santamonica.gov/blog/addressing-homelessness-questions-and-answers-on-santa-monica-s-anti-camping-ordinance.

Zillow. Santa Monica, CA Housing Market: 2025 Home Prices & Trends. Accessed April 16, 2025. https://www.zillow.com/home-values/26964/santa-monica-ca/.