OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

The Post-Postmodern Condition

“The Last Revolutionaries: Artists in Times of Rectification,” with speaker Gean Moreno and respondent Jaleh Mansoor, is the second in a series of virtual public talks entitled Dominance and Revolution: The Image, the Struggle and the Use of Force, part of CalArts’ Spring 2022 Aesthetics and Politics Lecture Series. The dialogue can be viewed live on March 17 at 12:00 pm PST (as well as streamed anytime after) on the Aesthetics and Politics YouTube channel.

Gean Moreno is the Curator of Programs at ICA Miami, where he founded (and currently runs) the Knight Foundation Art + Research Center, a “graduate-level initiative dedicated to fostering a more robust and critical dialogue in the South Florida region and beyond.” Moreno is also the editor of In the Mind but Not from There: Real Abstraction and Contemporary Art, an anthology of essays and visual projects published by Verso in 2019, which uses the Marxian concept of “real abstraction” to link the complexities of the present contemporary conjuncture with current cultural production.

In the book’s introduction, Moreno describes the state of contemporary art as somber, yet dynamic and extravagant, where the past decade of financialization has subsumed the art object and furthermore abstracted it into a banking tool — leveraging and liquidating it into a currency through investment products, such as art-backed lending. In other words, he contends that art has entered a new dimension, an immaterial state of “collaterizable entity,” supercharged and ballooned into something more than itself, simultaneously being trapped, while late-stage capitalism entirely disregards its actual content, meaning or self-definition. However, despite a self-awareness of this dynamic within much of art itself (especially by its producers), this contemporary reality does not seem to muster a response strong enough to curtail this transformation, let alone mount a potent critique of it. At the same time, any attempts to re-mystify the art object to the potentiality of its boundless presence (in an attempt to free it from its entanglement through assigning to it a kind of modernist aura), actually ends up being a mere hamster-wheel or a placebo for the trauma of its new reality. Hence, contemporary art’s current mood of despair, except for those lucky few who benefit from its facile asset valorization.

Therefore, Moreno posits the question, how does this new reality “manifests itself in the actual production or circulation of contemporary art?”1 And in turn, he asks various critical and social theorists, contemporary artists and curators to work through the pressing issue, along with some other related topics/questions. He does so in a pursuit not only to better understand the question itself, but also to find new prospects for intervention, and perhaps even resistance.

From Analysis to Aesthetics

One of those contributors to the book is Victoria Ivanova, a Ukrainian-born critical theorist based in London and a co-founder of Real Flow (an on-going research and development platform for finance and art), whose work searches for answers not outside of the contemporary art system, but rather from within it. In her contribution to the book, she revisits an essay/manifesto by art theorist, critic and curator (and former sculptor) Jack Burnham entitled “Systems Esthetics,” which was published in the September 1968 issue of Artforum. In it, Burnham proposes a reconfiguration of artistic production in order to reflect the current (at the time) transition to immateriality, a paradigm shift “from an object-oriented to a systems-oriented culture.”2 In his own simple, yet brilliant, single-line summary of that transition, “change emanates, not from things, but from the way things are done.”Ibid.

Burnham’s essay begins with the acknowledgement that within any technologically advanced, computerized society, power is located less in the material (or modernist) symbols of wealth than in information itself. In other words, he recognizes the “rise of the logics of abstraction and circulation,”3 and in turn the shift in focus of the state’s changing priorities to issues of organization, “where all living situations must be treated in systems hierarchy of values.”Ibid.2 Here, Burnham’s own interests coincide with an explosion of enthusiasm for an instrument that defines and manages these new concerns, called systems analysis. In a side note, system theories did not originate in the arts but through the science of biology and its concerns for the organization of interactions between complex components of organisms, from which it was then applied to various other fields. However, according to a Rand Corporation report on military decisions at the time, systems analysis should not be taken to be pure science but “still largely a form of art.”4 And this is precisely what Burnham does in his essay — takes this techno-economic paradigm and applies it to postmodern art practice of the 1960s, arguing that such systematic relations already exist within it,5 and therefore there is an overlap between the systems of both theoretical and artistic concepts. In turn, this shared conceptual space leads artists to begin using systems themselves as an artistic medium — not so much to mirror the larger social, political and economic context of the time, but as a method for surviving in the cultural marketplace.

Systems esthetics is the term that Burnham coins in the essay for the latter-described dynamic, along with the prophetic claim that it “will become the dominant approach to a maze of socio-technical conditions rooted only in the present.”ibid.2 For Burnham, what defines a system is its “conceptual focus” rather than its material limitations. Therefore, any condition, either within an art context or outside of its boundaries, may be regarded as a system. He also recognizes that in a culture that is continually moving away from industrial labor and production, the most prominent cultural producers “best succeed by liquidating [their] position as artists vis-a-vis society” — in other words, reducing the distance between “artistic output and productive means of society.”ibid.2 This may be best understood in contrast to Clement Greenberg’s well-known theories of modernism, in which a separation of art from the rest of the world takes precendent,6 and where the materiality of an art object limits its shape and boundaries albeit its transcendence being simultaneously contingent on it. Burnham openly rejects that rupture because the regularity of a system may be altered in the immaterial, such as in time and space, and its behavior managed both by “external conditions and its mechanisms of control.”ibid.2 This downgrading of form (and craft) in art creates an opportunity for it to actually become available for an array of pertinent issuesibid.6 including “maintaining the biological livability of the Earth, producing more accurate models of social interaction, understanding the growing symbiosis in man-machine relationships, establishing priorities for the usage and conservation of natural resources, and defining alternate patterns of education, productivity, and leisure,”ibid.2 all of which continue to have relevance in contemporary art today.

The Show of Shows

The issues tackled in Jack Burnham’s essay have a striking parallel to sections of French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard’s seminal work “The Postmodern Condition.” Published over a decade after “Systems Esthetics,” in 1979, this book confronts the rise of information in the rapidly-transforming postmodern era. As Lyotard points out, when scientific knowledge becomes more and more digitized (or computerized), as well as more exterior to any particular individual, there are a number of profound shits. First, the transfer of information is not only easier and faster, but what is considered knowledge is altered — it is no longer treated as an end in itself. Eventually, only the knowledge that is valued as informational commodity, which could be accumulated and traded, would be the one that is prioritized.7 Subsequently, this “neoliberal functionalization” of information ends up driving a process known as “globalization,” where international corporations are the ones best suited for commodifying information at large scales. This sudden growth of corporate power furthermore changes global power dynamics by shifting authority away from states and transferring it to multi-national entities that exert, and even dominate, unparalleled political influence.ibid.

In addition to globalization, the loss of individual power through the externalization and commodification of knowledge begins demanding a new kind of “sensibility” or self-awareness, due to the fact that human relationship to materiality, and ultimately to the world, had fundamentally changed. The postmodern actually challenges the concept of the human who envisions, who authors and who creates, but is no longer valued as such an integral part of these processes. In other words, a prior anthropology of labor had been upended. This loss of identity in relation to work and production in the material sense, results in a kind of insecurity and futility, expressed not only economically or socially, but existentially as a loss of purpose.8 These newly transformed relationships are best illustrated in Les Immatériaux, an influential exhibition co-curated by Lyotard at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris in 1985, which in many ways was a physical manifestation of “The Postmodern Condition.”

Les Immatériaux was a major cultural event in France. It occupied the entire fifth floor of the Pompidou and was the most expensive exhibition mounted by the center up until that time.9 Roughly translating in English to “the immaterials” or “the non-materials,” it was divided into five major categories or sections.10 Each contained several zones, together encapsulating a total of sixty sites that brought an impressive array of objects and artworks, including the latest mechanical robots and personal computers, holograms, 3D films, interactive installations, plus paintings, photographs and sculptures.ibid.9 Rather than the traditional, white-cube environment with neutral lighting, visitors to the exhibition were confronted by a chaotic and intentionally unsettling, dark-gray atmosphere consisting of a theatrically-lit maze of large, raw metal mesh sheets that hung from the ceiling — all conceived as a startling dramatization for “the postmodern condition.”

Most of the technologies showcased there were harbingers of ones that are currently deeply intertwined in contemporary life, from the most obvious, such as the internet, to the more invasive, as in data collecting, surveillance and social media. A prophetic warning of the latter, the point of Les Immatériaux was, in a way, to shock visitors into a self-awareness. It was a loud call not to admire the new inventions by communication technologies at the exhibition, but rather to question the relation between humans and the modern desire to become masters and possessors of nature. In other words, Lyotard wanted to liberate humanity from the modern paradigm, and to “release material from the prison of the industrial revolution.”11

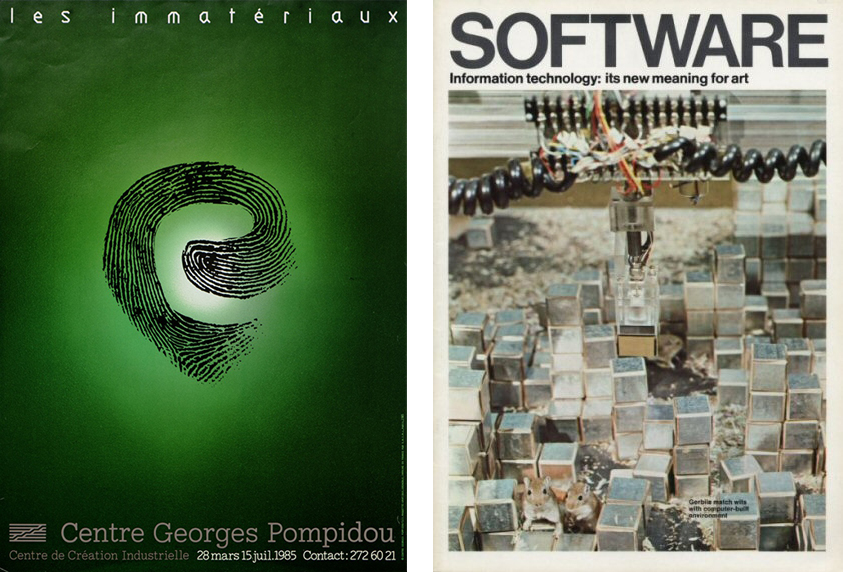

Poster from the Les Immatériaux exhibition in Paris, France (left) and catalog cover from the Software exhibition in New York.

Software as a Show

Another exhibition that held similar aims is Jack Burnham’s Software at The Jewish Museum in New York, however, it is much less known. On display some 15 years prior to Les Immatériaux, in the fall of 1970, it also served as a material manifestation of ideas explored in an earlier essay by its curator, in this case “Systems Esthetics.” It was an ambitious visualization of the essay’s main thesis, that art is essentially a system, and it presented scientific experiments by research teams and scientists alongside conceptual art projects.

One of the objectives of the exhibition, according to Burnham’s introduction to the catalog, was to stress the fact that information is “simply a measure of response between sender and receiver.”12 Here, he is interested in information’s ability to alter human behavior as it becomes “the measure of [that] data’s worth,”ibid. which in turn makes it function as a commodity. Another purpose of Software was to undermine traditional “perceptual expectations” and behaviors that visitors bring to an art exhibition. In other words, the ideas behind the exhibition were meant to detract from the idea of art as a system of “tangible expectation and predigested signs.”ibid. Therefore, on one hand, the machines in the show were not to be perceived as art objects, since they were simply means of relaying information, while on the other, any appearance of an art object was to be regarded as a mere fraction of a vast communication structure surrounding it.ibid.

In a way, as the art object yielded to “relations,” art in Software became a “catalyst and a connector,” its rationale within the exhibition was built on the premise of people interacting with information, whether other “living creatures, commands written on the wall, printed teletexts, or various kinds of machines.”13 One of the artifacts/projects, “Seek,” by the Architecture Media Group M.I.T., was a computer-controlled environment that reconfigured itself in response to the behavior of the gerbils living within it — a kind of ecosystem disrupted by the actions of a robotic arm. Another was conceptual artist Hans Haacke’s “Visitor’s Profile,” which encouraged exhibition attendees to input their personal information into a computer that then formulated it as statistical data about the audience of Software. In the exhibition’s catalog, Burnham prophetically warns about the dangers of digital data files on individuals which “continue to be an extremely serious threat to human rights, and one against which there are few real protections.” He acknowledges that this produces a self-fulfilling prophecy — a kind of paradox, in which humanity cannot survive without technologies that are “as dangerous as the dilemmas they are designed to solve.”ibid.12

Still image from Real Flow’s prospectus video.

Art Rescuing Art

Returning to Victoria Ivanova, she points out something that remains unsaid in Burnham’s essay. First, she argues that the technological (and aesthetic) changes, which he so well prophesied, not only affected the social but they were accompanied by an economic shift from industrial to financial-investment economies. In addition, she locates a “slippage” in the “disjuncture” between his systems esthetics — the open-systems art (as showcased in Software) which “re-presents” systems based on abstraction and circulation through their capacity for critical reflection, and systems art — the “representative” of systems whose decision-making “impacts the management and governance of systems at large.”ibid.3 It is in the latter, where Ivanova finds ways of intervening.

She begins by exploring the public lectures of Belgian philosopher Michel Feher,14 who contends that in an economic system that’s driven by financial investment, the empowered are those who actually have the capacity to determine the criteria for accreditation of investment-worthy ventures, i.e. rating agencies. In contemporary art, which ever since postmodernism has no longer relied on “material foundations” to be validated as such, these rating agencies are the institutional gatekeepers, such as art critics, curators and museums. And by applying Feher’s framework of financialization to art itself, Ivanova argues that ever since postmodernism art has operated as a “quazi-financial regime.”ibid.3

However, cuts in public funding for the arts during the past decades, and the increasing reliance on private money as a result, has made contemporary art’s “rating agencies” having to prove their “credit-worthiness” to its investors, which in this case are collectors and philanthropists. To counter that, the strategy of art institutions during this time has been to boost the capital value of contemporary art, with a pay-off only in the social aspect of investing but not in the “systemic efficacy” of it, thus making it a low-risk target for players in the financial market.ibid.3 Therefore, one way of challenging this dynamic is using Burnham’s “system art” and (through applying Faher’s framework to it) deploying it to modulate the “circulation-based codes” of the contemporary art “regime,” in other words to produce agencies that modify “the criteria for accreditation,” and in turn reshape the expectations placed on art and the values it represents.ibid.3 This would involve working more than just aesthetically or discursively, but in the “infrastructural back end” of the systems, reconfiguring things such as “market relations, institutional and legal protocols.”ibid.3 In other words, it would mean a contemporary art world that actually participates in changes that “emanate from the way things are done,” according to Burnham’s own aforementioned words.

Art’s Way Forward

Currently, we seem to be in a convergence, a shift, and even a rupture between postmodernism and a period of financialization of contemporary art — that new existence of entrapment by late-stage capitalism as a “collaterizable entity,” from which Gean Moreno’s concerns originate. And perhaps this is not simply an extension of the postmodern, but a brand new “era.” Judging from the recent embrace of NFTs (not-fungible tokens) by the art world, that seemingly-free immaterial space, capitalism still found a way to valorize and ultimately subvert it. Clearly, whatever this is, is here to say. Through that acceptance, the only way to possibly intervene in this new period is within the system itself, just as Victoria Ivanova suggests.

However, something Fredric Jameson pointed out previously in regard to postmodernism may be even more relevant today. Perhaps it is just as true for our existence within this new period that “its facile repudiation is as impossible as any equally facile celebration of it is complacent and corrupt.”15 If that is the case, then history may be just as pivotal as the role of art in it. Not only will it provide context, but also inspiration and perhaps simply hope. Essentially, even Lyotard urged those in the grasp of the postmodern to ultimately seek that which is not reducible to commodification and not representable in the reality of the present. This is what allows creative individuals who witness the latter to make highly unexpected and disruptive moves within it, causing displacements or even completely disorienting it. Thus, it would be wise to turn to Lyotard’s words in the Appendix section of “The Postmodern Condition,” now in a new context. There, he went even further by saying that “artists and writers must be brought back into the bosom of the community, or at least, if the latter is considered to be ill, they must be assigned the task of healing it.”16

Footnotes:

- Moreno, Gean; “Introduction”; In the Mind but Not from There: Real Abstraction and Contemporary Art, Verso, 2019.

- Burnham, Jack; “Systems Esthetics,” Artforum, September, 1968.

- Ivanova, Victoria; “Art, Systems, Finance”; In the Mind but Not from There: Real Abstraction and Contemporary Art, Verso, 2019.

- Quade, E.S.; “Methods and Procedures”; Analysis for Military Decisions, The Rand Corporation, 1964, p. 153. Also, see Footnote 2, above.

- In the essay “System Esthetics,” Burnham also argues that in a postmodern socio-technological culture “scientists and technicians are not converted into ‘artists,’ rather the artist becomes a symptom of the schism between art and technics.”

- Jones, Caroline A.; “Caroline A. Jones on Jack Burnham’s ‘Systems Esthetics’,” Artforum, September, 2012. In addition, see Clement Greenberg’s “Modernist Painting” as part of Voice of America’s Forum Lectures in 1960, as well as his two major collections of essays Art and Culture, published by Beacon Press in 1965 and Late Writings by University of Minnesota Press in 2007.

- Lyotard, Jean-François; “The Field: Knowledge in Computerised Societies”; The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, 1979 (English translation published by Manchester University Press in 1984).

- Lyotard, Jean-François; “Album et Inventaire,” Les Immatériaux exhibition catalog; Centre Georges Pompidou, 1985, p. 16 and p. 26. Also, see Footnote 11, below.

- Hudek, Antony; “From Over- to Sub-Exposure: The Anamnesis of Les Immatériaux,” Tate Papers, 12, Autumn 2009.

- The five categories (or sections) of Les Immatériaux, based on the Sanskrit word root “mat,” referring to making and building by hand: matériau = support (medium), matériel = destinataire (to whom the message is addressed), maternité = destinateur (the message’s emitter), matière = référent (the referent), and matrice = code (the code).

- Hui, Yuk and Broeckmann, Andreas; “Introduction,” 30 Years after Les Immatériaux: Art, Science and Theory, Meson Press, 2015.

- Burnham, Jack; “Notes on Art and Information Processing,” Software exhibition catalog, The Jewish Museum, pp. 10-14.

- Terranova, Charissa; “Software: Jack Burnham and the Medium as System,” Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, 100th Annual Meeting, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston,MA, March 1-4, 2012.

- Feher, Michel; “Investee Activism: Another Speculation Is Possible,” The Age of Appreciation: Lectures on the Neo-Liberal Condition, 2013-2015, Goldsmiths, University of London.

- Jameson, Fredric; “Theories of the Postmodern,” Postmodernism or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Duke University Press, 1991.

- Lyotard, Jean-François; “Appendix: What Is Postmodernism?”; The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, 1979 (English translation published by Manchester University Press in 1984).