OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

The Paint Tube to Warhol: the Valuing of Art in the Mechanical Age

The way we decide what art is and how it is valued is a political determination. In other words, social, economic, and technological developments are inherently tied to the unfolding of artistic movements. Though there is a tendency to distinguish artistic practices from political ones (the way art and politics are categorized makes them seem almost like opposites), this is a misconception.

Scholars Jennifer Ponce de León and Gabriel Rockhill joined the CalArts MA in Aesthetics and Politics Program for a public lecture titled “Power of Aesthetics, Aesthetics of Power.” They discussed the seemingly unnecessary distinction between artistic and political practices. In particular, they refer to the labor and social relations of production as an innate aspect of art-making, rendering it as a political practice. In this post, I examine two particular technological developments that reveal the importance of studying those underlying relations. The first technological development demonstrates how artistic and political practices are connected, and the second shows the nature of politics in the arts. What I find is that avant-garde movements, like any major art historical development, are directly adjacent to the political practices of the times. To begin, I look to the invention of the paint tube.

The Paint Tube

Prior to its invention, artists would either paint indoors or riskily transport paints using sacks made from pigs’ bladders or glass containers (though these methods were seldom used). Pigments were more often mixed manually, and finished paints would be left out of palettes, greatly shortening their shelf life. The Industrial Revolution changed these methods. Materials became much more accessible and more colors were available, thanks to advancing sciences of the time. In 1841, an American painter named John Rand constructed a small metal tube to hold his paints (Hurt 2013). While this was a simple invention created out of artistic necessity, it was the political state of the world at the time that allowed its proliferation. The tube was incorporated and redesigned, until eventually the art community agreed upon the metal tube with screw top.

More specifically, the Industrial Revolution can be understood as a political, economic, and social movement that occurred primarily in the United States and Europe during the 16th-17th centuries. Among other things, was the corresponding shift to factory production. This shift was responsible for a new societal focus on consumer products, as the increased production allowed for larger quantities of goods to be made at lower costs. It also resulted in a new discourse on labor practices, with particular emphasis given to child labor and poor working conditions. It can then be assumed that any mass-produced invention from that time bears the baggage of unjust labor practices. In turn, the paint tube’s life revolves around these economic and social dynamics. As with any other commodity, the life of a paint tube begins with the workers who put the parts together. It does not stop there. Its life continues with the patents bought and sold to exercise monopoly power, the ships that transport the merchandise across the seas, the construction of specialty stores that sell the paints, and the social and economic relationships between the artists and the patrons who exercise ownership over the final art object.

The production process is political, both because of the context of the Industrial Revolution, but also because of the lasting cultural impact on art history. The trajectory of art changed entirely as paint began to move throughout the world through tubes. For example, the transportability of the paint tubes facilitated the Impressionists. Prior to this time, in-studio painting was the standard. Once the paint tube was invented, painters could finally exit the studio, ergo the transition to en plein air painting (Hurt 2013). This was the act of creating a finished painting entirely outside. With this new capacity, en plein air painting changed what was being depicted. Now, movement was being reflected in painting; there would be children playing, boats passing, and (perhaps most significantly) changing light. As a result, the use of color exploded in painting (consider the work of Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir).

In general, the paint tube gave artists permission to better reflect the reality of the world at the time through painting. Before, almost every part of painting was mediated by the rich. The materials, labor, and final work were all expensive, and the rich were the only ones who could pay the cost. Industrialization opened up access to all sorts of materials and methods, and the painter was able to distance themselves from the bourgeoisie and began rendering images of the outside world. The change of subject had significant political implications. It started to reveal class dynamics in society that had never been seen in the venue of painting. Prior to this time, it was the bourgeoisie that was depicted for the most part; nobles dawned in fancy clothes, lounging around in their lavish homes. But because en plein air meant painting the public world, class relations became visible in art. Georges Seraut’s 1884 Bathers at Asieres portrays working-class people, and is totally juxtaposed with the wealthy subjects of his 1886 A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. Wealth inequality was apparent, and the divide between the laborers and the patrons was clear and stark.

Advancements in science and technology, and the resulting advancements in production and manufacturing, became extremely pertinent to artistic practices during the Industrial Revolution. In other words, the cultural and economic movement of the world plays a considerable role in what occurs in the art world. The ongoing reign of the paint tube expresses this. The effect is not an anomaly; it remains true in modern contexts.

Warhol, the “Machine”

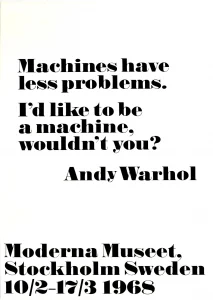

The transformations provoked by industrial production in art do not end with the Impressionists. Thierry de Duve and Rosalind Krauss discuss Andy Warhol’s philosophy on the manufacturing of art and the role of labor in art making in their 1989 October article “Andy Warhol, or the Machine Perfected”.

De Duve and Krauss’ article begins with a discussion of value. There is value placed on an artwork as a viewer; this makes up its artistic value. Such value is difficult to discern, and personal judgements determine how an artwork is valued, meaning it is unique for every individual and every artwork. Beyond the artistic value, works of art also express labor-value, which determined by how much labor was employed to create an artwork. There is also use-value, determined by how much artwork can be used, or its utilitarian contribution. Perhaps most influential to today’s art market is exchange-value, an effect of the monetary worth of artworks. To determine the ultimate ‘value’ of an artwork means a studying the balance between all the different sorts of values an artwork can hold.

De Duve and Krauss investigate the valuing of art and its relation to labor-time and other kinds of value. With Warhol, his conception of labor begins with the American dream. He was a first generation American, born of two Austrian-Hungarian immigrants. The American dream that Warhol’s parents were chasing by moving to the United States revolved around capitalism. To be successful in America for them meant achieving the American dream, roughly equivalent to participating in American capitalism. Being able to drink a Coca-Cola (as Rockhill pointed out in his lecture), the same drink Marilyn Monroe drank in an advert, means you are seen as and protected as an American. Warhol was motivated by these viewpoints in his artistic practice. Along with the other pop artists of the time, he pulled images from advertisements and popular culture to represent the American dream, the capitalism that comes with it, and most importantly, the consequence of mass consumerism (de Duve 6).

In capitalism, labor is treated as a commodity. A cynical view of capitalism and the American dream has labor being valued less than the commodity that is ultimately produced. But Warhol did not see this as a problem, and he vehemently applied the concept to art-making. He believed in an art-value system that depended on the consumption of the art, rather than the production of it (de Duve 9).

Warhol’s focus on the consumer was a reaction to the preceding art movement of the New York School. The reason the work of that movement was valued so highly was because of the unique methods that were introduced. Pollock and Frankenthaler laid their canvases on the floor to paint, they broke down and threw away what it meant to paint properly, and this what has made their work memorable and worthy. Most distinctive is how such art was made to express the process, and the New York School did not give a damn about what the consumer thought of it. The proliferation of mainstream popularity of the color field and gesture painters came from a celestial alignment: modernist painters moving to the United States during World War II, followed by references to a “New York School” and praise by Clement Greenberg. But the movement was never motivated by commercial success in the way Pop Art was. Pop Art specifically sought the praise of the consumer.

Pop Art represented those who felt alienated by the New York School, a movement that was highly intellectual and arguably conceptually inaccessible for the average person. As a response, Pop artists created work that was the opposite. Anyone could access a Campbell Soup can or Marylin Monroe through trips to the grocery store or watching television. The bright colors were easily stimulating. The systems of American capitalism had already infiltrated the art world during the New York School, so by the time Pop art came around, art had already transformed into a financial venture. The psychological accessibility of Pop art is what sets its history apart from its predecessor, and the result was an art world centered on the consumer rather than the artist. In other words, it was about the product, not the process.

De Duve and Krauss relate the changing metric of valuing artwork to the invention of the photograph. This invention occurred at a similar time as the paint tube, and, like the paint tube, it contributed greatly to the development of modern art. The ability to capture images changed the purpose of painting. Before, painting was mostly intended to be representational. The photograph rendered that intention obsolete. No painting could ever come as close as a photograph in terms of the precision of representation. Furthermore, a photographer manifests the image utilizing a fraction of the labor-power and -time as compared to a painter.

The manner in which this affects art is a concept that consumed Andy Warhol, evidenced in part by his use of silk screen. The device of silk-screening allowed its technicians to quickly recreate an image over and over again. The amount of work produced from a silk screen was unmatched by any other method of printing at the time. It is almost unbelievable when placed next to the painstaking methodology of Renaissance painters. This offers a question: what happens to the value of an artwork when the labor-time used to create it changes? Is a painting that took hours or weeks to create inherently more valuable than a painting that took seconds, as Warhol’s prints did? The answer is obviously no, especially when you encounter the monetary value placed on Warhol’s at auction. Therefore, the difference is the kind of value that attaches itself to an artwork.

It is through these concepts that de Duve and Krauss qualify Warhol as a “machine”. A machine treats art as a commodity, the value of which is determined by a socially determined system of exchange. Under that system, an artwork does not necessarily require high-value labor or time in order for it to have a high exchange value. As just mentioned, the exchange value is socially determined, meaning it is ultimately concerned with the consumer. The authors point to the photograph as a catalyst for the development of the machine: “Ever since Delaroche, Champfleury, or Baudelaire expressed the fear, inspired in them by photography, of seeing the painter replaced by a machine, modern painters—the great ones, those who deserve to be called avant-garde—have responded with a manifestation of their desire to be one” (de Duve 10). A highly skilled realistic rendering in a painting will never match the realism of a photograph. Painting was forced to evolve to stay relevant, and one reaction was to mimic the swift movement of a camera capturing an image. The Impressionists, thanks to the paint tube, painted the changing light of day and brought a unique gestural quality to light that captured the movement of a single moment, the way a camera can. Warhol mimicked the automatic nature of a camera, the instantaneous and mass production of an image.

Conclusion

In both the case of the paint tube and Warhol’s machine-ism, it was political circumstances that ultimately informed their lasting impacts. The rise in the capitalist production of goods fueled by the Industrial Revolution resulted in a consumer-centric society that poured over into the art world, as evidenced by the Pop art movement. The dynamics between political developments, that is, social and economic developments that are deeply connected to the dynamics between and within communities, are responsible for some of the most important art historical developments of all time. That rise is what allowed the invention of the paint tube to be possible, and Warhol’s practice explicitly reveals the significance of the societal shift towards capitalism. Furthermore, the paint tube facilitated the Impressionists, which set up the art world for future avant-garde movements like Pop Art. The obsession with American capitalism (of which is often exhibited by American immigrants, like Warhol’s parents) along with the technological methodology of the factory produced what may be the world’s most famous modern painter. These facts prove that politics is by no means absent from artistic practices; in fact, it is integral to them.

Citations

de Duve, Thierry, and Rosalind Krauss. “Andy Warhol, or The Machine Perfected.” October, vol. 48, 1989, pp. 3–14. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/778945. Accessed 11 Jan. 2023.

Hurt, P. (2013, May 1). Never underestimate the power of a paint tube. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/never-underestimate-the-power-of-a-paint-tube-36637764/

Ponce de Leon, Jennifer, and Gabriel Rockhill. “Power of Aesthetics, Aesthetics of Power.” Critical Discourse in the Arts, California Institute for the Arts, The Armory Center, September 16, 2022.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Phenomenon-color-app-tin-tube-631.jpg)