OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Sonic Resistance: displays of sound in the work of Lawrence Abu Hamdan as read through Shana L. Redmond’s 2020 “Everything Man: The Form and Function of Paul Robeson”

In Shana L. Redmond’s 2020 book Everything Man: The Form and Function of Paul Robeson, Redmond explores American singer, Paul Robeson’s use of sound and his Voice as political strategies of sonic resistance and collective gathering. The following essay will use Redmond’s analysis of these aspects of Robeson’s career and focus them towards the contemporary Jordanian-born artist, Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s practice.

Born in 1985 in Amman, Jordan, Hamdan describes himself as a “private ear”[1], investigating the political parameters of sound and listening in his work. In calling himself a “private ear”, a play on the phrase ‘private eye’ (a colloquialism for a private investigator), from the offset, Hamdan frames his positioning as an artist beyond solely aesthetic, object, or production-based concerns. Placing himself in the role of investigator, Hamdan’s work is closely aligned with the potential and actuality of political engagement in contentious, contested and abusive events concerning and influenced by sound, audio and listening.

In Hologram, the first chapter of Redmond’s book, she notes:

Robeson’s sound migrations – the performances that allowed his detained or silenced voice to take flight – are indicative of a rising wind of Black internationalism and compel an investigation of the relationship between sound and sight, fixity and enclosure, geography and citizenship.[2]

A singer, musician and political activist, Paul Robeson used his voice to reach audiences overseas and bring people together who were fighting various global and national injustices. Redmond illustrates this with examples such as Robeson presiding over the 1955 Bandung Conference in Indonesia in which he gave a speech and sent song recordings[3] and in 1957 when he sang to the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) in South Wales from a studio in New York City. Describing Robeson’s audio interventions as “sound migrations” in the quote above, Redmond aligns the musician’s use of sound – both as a bodily act and in its technical abilities to travel internationally – with ideas around migration, nationhood, and citizenship. As Redmond notes, his physical absence and therefore presence only through these powerful sonic deliveries was not merely performative but done out of a necessity. Between 1950 – 1958, the United States revoked Robeson’s passport, the McCarthyite anti-Communist government suspicious of his vocalness around human rights and his pro-Soviet stance[5]. Thus, sending and then using a sound recording from Robeson during this period becomes inherently tied to American politics, international relations and radical or grassroots efforts to circumvent the restrictions put in place to halt the spread of Robeson’s views and political outlook. It is not only that what he is saying might be radical or counter to official American government stance, but that the mechanics, optics, and context in which what he’s saying is dispersed becomes both protest method and action.

In 1955, the Bandung Conference, the first large-scale meeting of African and Asian countries, took place in Bandung, West Java, Indonesia. The conference included a number of newly independent countries and discussed international cooperation between them. From afar, Robeson participated in the event. Unable to travel as his passport had been revoked, instead he sent a voice recording including a speech and three songs, “No More Auction Block,” the peace ballad “Hymn for Nations,” and his anthem “Ol’ Man River.”[6] Redmond notes, “His seditious labors by phone exposed the fascism of the state as he defied the ban on his travel by sending the sounds of his body under the ocean”.[7] Here referring to Robeson’s use of sound to communicate with his political comrades abroad, Redmond again highlights the importance of sound technology in evading the confines of state-based physical and creative arrest. Interestingly, Redmond also notes, referring to Robeson’s inclusion in the Bandung Conference, “Even with this intervention, however, the appearance of Paul’s Voice on tape does not diminish its inevitable fade and decay as material artifact.”[8] In this way, Redmond reminds us of the physical fragility of sound which may either be lost or recorded through technological devices, and then of course carefully preserved to retain such recordings. Redmond also points out the relation and tension between Voice as immaterial – moving beyond borders – and physical – coming from and uttered through a body. Equally, this highlights the rigid and specifically movement-based restrictions placed on Robeson through his passport confiscation – a mixture of symbolic and actual restraint.

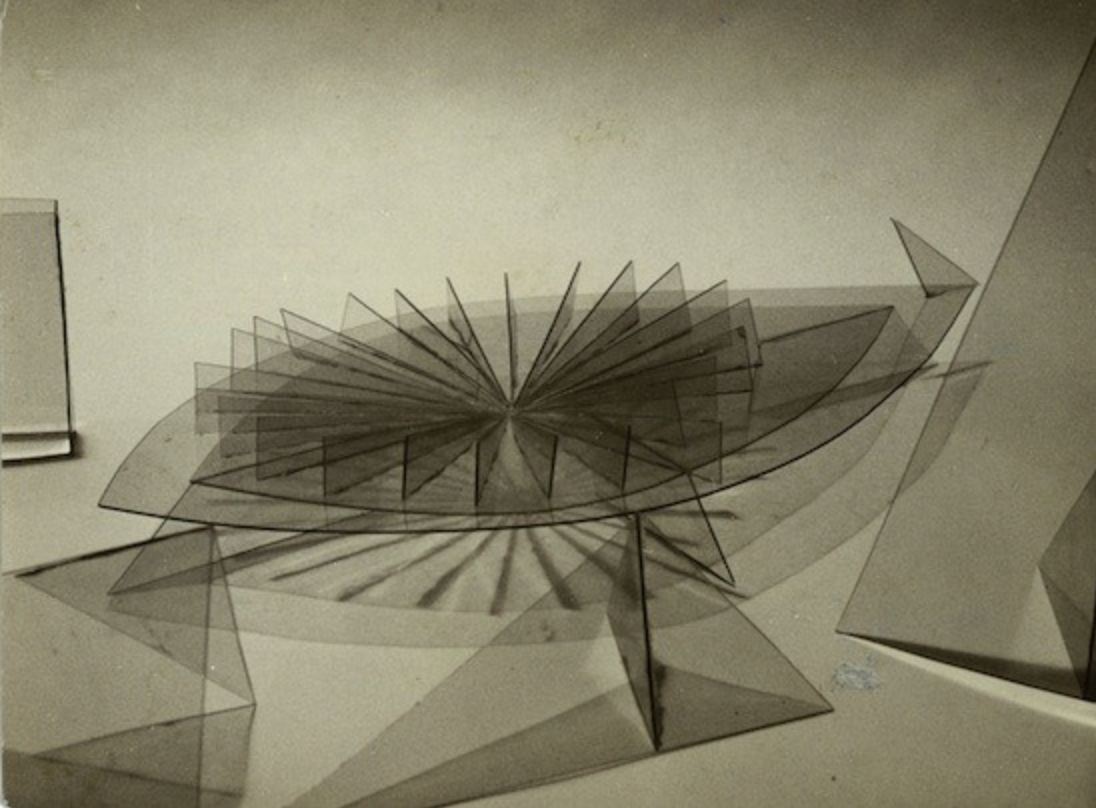

Saydnaya (the Missing 19dB), Hamdan’s 2017 installation commissioned by the UAE-based Sharjah Art Foundation, uses sound and voice to expose political exploitation and control of power. What is particularly impactful and complicated in this work – and Hamdan’s practice overall – is the way the artist directly uses evidence-based sound material that exposes human rights abuses and infringements on freedom to then re-orient these sonic records of oppression as potential sources of emancipation. Once reconstituted in his work as art, they remain as stark record and evidence, while at the same time taking on a new afterlife for audiences to consider and react to what they hear and see. Like the political activism of Robeson, the line between political action and art is blurred with Hamdan – for example, his 2012 piece Phonemes, a print installation consisting of diagrams made in response to a meeting Hamdan held in Utrecht to discuss the “phonetic policies that govern the acceptance or rejection of migrant asylum applications in Europe”[9], was eventually used by asylum seekers when presenting to an immigration judge in the Netherlands and at an asylum deportation hearing in the UK[10].

Saydnaya is an installation including a chromogenic print in a lightbox, a 12 minute 48 second sound piece and an automated mixing deck. The work examines both the strategic use of sound in Saydnaya, an Assad-regime run prison in Syria and documents the sound-based experiences of the few released prisoners whose vision was restricted while there and so must rely on what they heard to provide “earwitness testimonies”[11] of violations in the prison. The 19dB mentioned in the work’s title refers to the drop in volume between normal conversational sound levels, the sound level permitted in the prison before the 2011 protests and the decreased sound level permitted after the 2011 protests. This is visualised through the lightbox. At the end of the audio piece installed in a dimly lit room, the lightbox illuminates to show the chromogenic print that visually documents the 19dB drop. The previously playing sound piece documents the former prisoners’ experiences at Saydnaya, automated through a mixing deck with motorized volume control and moving “according to the voices one is hearing in the room”[12]. In this way, Hamdan’s installation combines both the techniques used by the Assad regime to strategically control sound and therefore the spread of information, and the sound-based memories and audio evidence of the former prisoners collected after their release for the purpose of Hamdan’s commissioned work. In other words, not only does Saydnaya provide a stark example of a political regime’s utilisation of sound as power, but also an example of how sound can function as documentation of abuse for potential justice in the face of human rights violation.

In reference to Robeson’s use of sound and the political parameters which surround it, Redmond aptly notes several formed relationships – sound and sight, fixity and enclosure, geography and citizenship. Various similarities arise when looking at the work of Lawrence Abu Hamdan. Equally, Redmond’s rightful focus on the proliferation of travel and internationalism in relation to music, politics, and Robeson’s mid-twentieth century career can be compared to Hamdan’s own career as an artist and the globalised art world that he currently inhabits. As has become a common observation when looking at contemporary art today, it is impossible to consider an artist’s work and practice in separation from their historical, social and political contexts. In this way, it feels pertinent to acknowledge Hamdan’s particular position within a globalised art world.

Although there is a similarity between how both artists understand the political potentials of sound (both in terms of control and emancipation), while Robeson’s career is defined in part by his inability to travel and vehement fight for the return of his passport, Hamdan’s career is marked by his celebrated and unrestricted participation thus far in global art world events. Significantly, Hamdan has appeared in more than eight international surveys of contemporary art – including the prestigious 2019 Venice Biennale, 2019 Sharjah Biennial and 2021 São Paulo Biennial – a distinction only true of 23 other artists worldwide[13]. Of course, these differences should be read in their political contexts – Robeson was working in a time and place of a more overt and hands-on local government approach to celebrity and public figure dissent (1950s McCarthyite America); Hamdan is working within a much more globalised system which has developed to understand the benefits of permitting certain celebrations of its own critique. In this way, while Robeson faced stringent backlash from the American government for his outspoken political leanings, Hamdan can arguably more easily navigate his critical stance.

This is of course not to suggest that politically oriented creative work is now entirely permitted nationwide. This type of overt state-based control can be seen in the last few years in many countries. One obvious example is the film industry in Iran, tightly controlled and monitored by the notorious Ministry of Culture. In similarity to Robeson, famous examples of bypassing these restrictions through technology can be seen in Iranian filmmakers such as Jafar Panahi who snuck his film created during his house arrest in Iran out of the country for the 2011 Cannes Film Festival in France via a birthday cake and Abbas Kiarostami whose banned films were routinely shown around Europe and then snuck back into Iran via underground streaming services.

When thinking about Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s practice in relation to Paul Robeson, it is interesting to consider the structural and contextual elements in their uses of sound and voice. By this, I mean not only the ways the artists utilise sound politically and aesthetically but also the way sound is organized, mediated and transmitted by them. This appears to be crucial to Redmond’s understanding of the complexities and potential of sound. Whereas with Robeson at Bandung, we see an example of how his creative practice was put towards ‘real life’ political event (sending his music to the conference), with Hamdan we see him take ‘real life’ events and re-construct them through art to be both crucially archived as proof but also transmitted in a new way through himself ultimately as a mediator. In this way, both artists grapple with ideas around presence and absence – the potential privilege and oppression of both, the ways to circumvent physical absence, the structures, and transmission of sound as powerful stand-ins for other absences, and the physical effects of sound on bodies present in space.

References

1. http://lawrenceabuhamdan.com/information

2. Redmond, Shana L. Everything Man: The Form and Function of Paul Robeson. Los Angeles: University of California Press. 2020. pg. 19.

3. Redmond, Shana L. Everything Man: The Form and Function of Paul Robeson. Los Angeles: University of California Press. 2020. pg. 22.

4. Redmond, Shana L. Everything Man: The Form and Function of Paul Robeson. Los Angeles: University of California Press. 2020. pg. 29.

5. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/ robeson#:~:text=His%20outspokenness%20about%20human%20rights,ultimately%2C%20to%20earn%20income%20abroad

6. Redmond, Shana L. Everything Man: The Form and Function of Paul Robeson. Los Angeles: University of California Press. 2020. pg. 23.

7. Redmond, Shana L. Everything Man: The Form and Function of Paul Robeson. Los Angeles: University of California Press. 2020. pg. 29.

8. 7. Redmond, Shana L. Everything Man: The Form and Function of Paul Robeson. Los Angeles: University of California Press. 2020. pg. 23.

9. http://lawrenceabuhamdan.com/conflicted-phonemes

10. http://lawrenceabuhamdan.com/conflicted-phonemes

11. http://lawrenceabuhamdan.com/saydnaya

12. http://lawrenceabuhamdan.com/saydnaya

13. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/biennial-artists-17-profiles-2127298