OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Rethinking Oil in an Ecofeminist Framework

Milk and Oil in California

Greta Gaard’s lecture at REDCAT presented a fascinating opportunity to consider interspecies justice as fundamental to ecofeminist critique and thought. Gaard began with a dream she had as a child. In the dream, an oil pump was drilled directly through a dairy cow in an open field, creating a violent mixture of blood, oil, and milk. From this psychoanalytic premise, Gaard skillfully tied the convergence of an economy of life, represented by milk, with an economy of death, represented by oil, under the broader context of bloody economic violence within capitalism. Like the dream itself, the logic of capitalism is not rational. Rather, it appears as a nightmarish flattening of life and death. Oil, created from the fossils of long-dead animals, can be exchanged equally with the milk produced by living animals (specifically mothers). To drive this point home, Gaard presented maps showing the locations of major oil drilling operations and industrial dairies in California. The maps are almost identical.

It would perhaps be wrong to call these maps “evidence” in support of Gaard’s childhood dream. Evidence suggests that the dream is an empirically verifiable premise that can be proved or disproved. Rather, the maps illustrate the relationship between capitalism and dreams, or more specifically, between capitalism and the monstrous, dreamlike realities it conjures into the real world. As Gaard goes on to explain, the overlapping locations of California’s major oil drilling sites and its major industrial dairies also correlate with high concentrations of poverty, disinvestment, and immigrant communities. If capitalism’s dreamlike ability to make the unreal real strikes one as magical or even liberatory, this third map reminds us of capitalism’s necessarily destructive implications. The surreal mixing of oil and milk in California’s central valley comes at the cost of high levels of air pollution and labor exploitation.

Gaard’s ability to weave together a feminist, materialist, and psychoanalytic critique was fascinating. The lecture opened up the opportunity to identify the surreal, subconscious currents that run through the networks of capital crisscrossing the largest state economy in the United States. As Gaard noted, this is particularly resonant in Los Angeles, a city whose economy depends mainly on selling fantasy and illusion. The lecture further allows us to consider how practices borne out of love and care, such as infants suckling at their mothers’ breasts, can be coopted and fed into the cold economic logic of capital. The implications of this are profound. As Gaard noted while describing the structure of modern industrial dairies, no one asks what the cows want. Armed with this outlook, we can approach the world as a site of exchange between human and nonhuman actors, between dreams and reality.

With that said, Gaard’s lecture did not seem to fully account for the implications of its own argument at times. Gaard spoke of the extraction of milk from cows in industrial dairies as a diversion of sorts. While milk primarily circulates between mothers and children, or as Gaard importantly clarified, capitalism diverts this flow between mothers and other mothers. In a capitalist system, milk becomes a resource to be extracted from cows and turned to profit—all the while, the dairy cows are worked until they collapse, and their calves are separated from their mothers to be raised until they can themselves be milked or slaughtered. Thus, once milk has been diverted into a system of capitalist exchange, the violence of its production becomes apparent.

However, oil has no comparable diversion. In Gaard’s framework, oil exists either as a capitalist commodity or doesn’t exist at all. The effect of this is to undercut the very point of the comparison between oil and milk. As a conceptual intervention, ecofeminism seeks to restore the vitality, agency, and subjecthood to those individuals and materials that capitalism has reduced to commodity status. Ecofeminism seeks to situate “humans in ecological terms and non-humans in ethical terms.”1 By suggesting that oil has nothing more to say, Gaard inadvertently limits the applicability of ecofeminism as a method. Gaard’s lecture illustrated the possibilities opened by this framing, which made her refusal to consider the potentialities of oil particularly disappointing. By this, I do not mean to suggest that oil be given a positive or liberatory valence. Rather, I simply suggest that the possibilities for considering oil’s psychoanalytic or metaphorical dimensions are likely more expansive than merely stating that it should remain buried below the earth’s surface. In fact, this response itself raises a psychoanalytic flag. Suggesting that oil remain subterranean and not be permitted to rise to the conscious surface carries more than a hint of a repressive tendency.

Rethinking Oil’s Conceptual Possibilities

The logical question that follows then is, how can we better think of oil’s conceptual possibilities? Gaard begins her discussion of oil with a description of the La Brea Tar Pits, a prehistoric pool of oozing oil and tar bubbling up in the center of Los Angeles’s Miracle Mile district. The Tar Pits are also home to an archaeological museum and have thus become a popular attraction for visitors to Los Angeles. Perhaps most important for the tourist appeal, though, are the life-size models of two wooly mammoths, an adult and an infant, watching in helpless horror as a third mammoth model futilely struggles to escape from the tar. Gaard suggests that the entertainment value of this scene derives from taking comfort in not being stuck in the tar oneself. For Gaard, this perspective depends on Western divisions between subject and object, and the inability or refusal of the former to extend empathy to the latter. This framing focuses primarily on the panic visible on the faces of the mammoths while sidelining the function of the oil itself. This misses a fundamental aspect of the display.

When the lighter elements of oil evaporate, thick tar is left behind, which acts as a fossilizing agent for the unfortunate animals trapped in it. This is an important part of the scene recreated at the La Brea Tar Pits. By depicting this initial moment of fossilization, the viewer is forced to reconcile not with the distance between now and prehistory but rather with its temporal proximity. The display’s sinister allure can be attributed to the horror the viewer experiences upon realizing that the tar pit, which fossilized prehistoric animals, persists to the present day. Oil collapses time, simultaneously showing us what remains from millennia past and what awaits us.

Finally, we can reinsert this understanding of oil into Gaard’s initial framework. If milk is pressed into capitalist exchange at the cost of depriving the infant animals for whom it is produced, oil can be understood along a similar line. Oil is a product of death and fossilization that occurs over a geologic timeframe almost too large to comprehend. When it bubbles up to the surface, it becomes a noxious symbol of deep time, forcefully connecting the contemporary observer to prehistory. Of course, like milk, oil can also be redeployed as the lubricant of capitalism itself.2 To the extent that capitalism presents itself as a historically transcendent phenomenon, the connections to the past that oil represents are erased in service of capitalism’s claim to an eternal present.

The effect of this reconceptualization would be to strengthen, not detract from, Gaard’s thesis. Ecofeminism’s theoretical power is in rectifying Enlightenment thought’s division of “man” from “nature.” It prioritizes the contingent, horizontal, and interstitial over the hierarchical, segmented, and rigidly rational. Ecofeminism values what has been discarded and devalued by Western thought. It would thus be contrary to ecofeminism’s primary tenets to dismiss oil as an irredeemable material. Just as milk connects mother and child, or animal and human, oil connects the present to the past. If milk creates horizontal connections, oil creates vertical ones. It is unavoidable that a substance which connects the present to the past via the process of fossilization would be imbued with an aura of death. It would be lazy to suggest that this deathly quality is synonymous with capitalism. Capitalism may posture itself as universal, but death truly is.

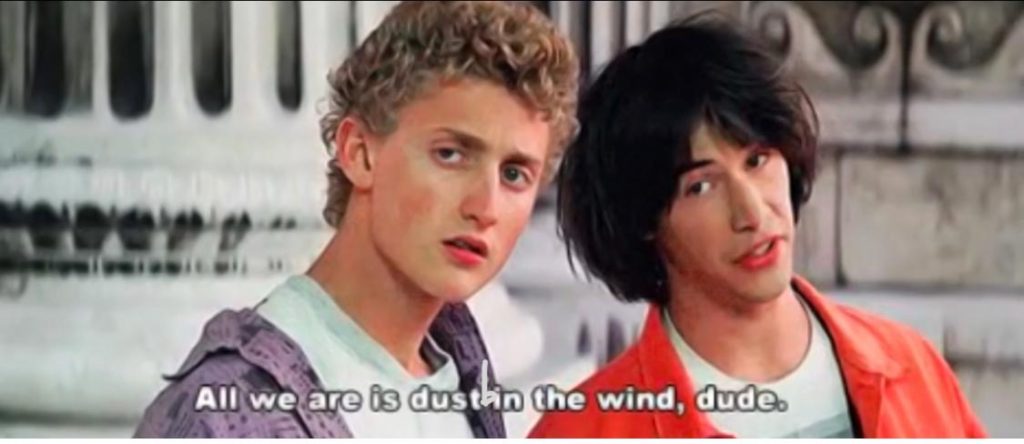

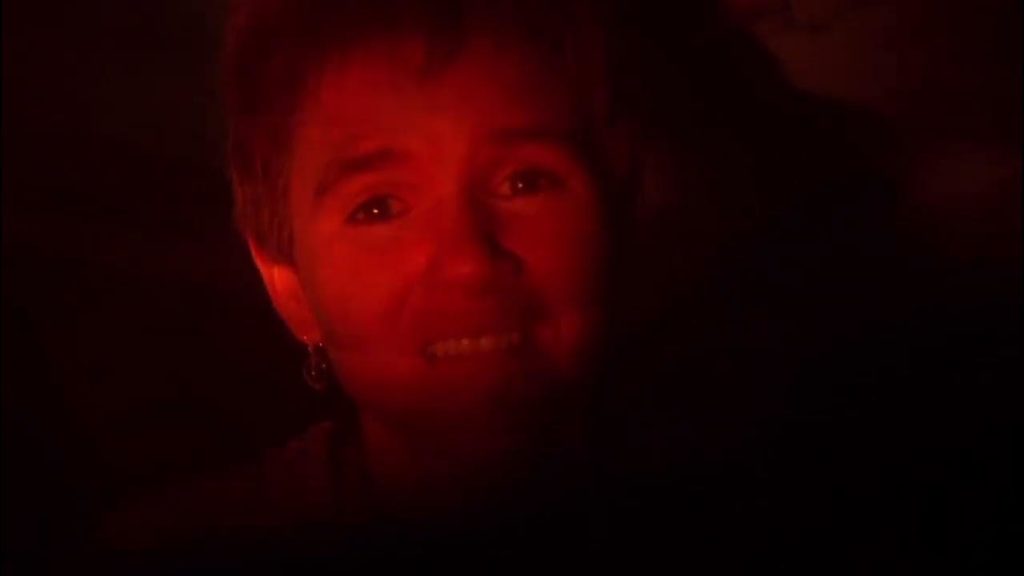

A still from the final scene of Miracle Mile (1988).

Diamonds in the Tar Pits

Gaard’s discussion of the La Brea Tar Pits reminded me of Miracle Mile, a 1988 movie filmed almost entirely on that stretch of Los Angeles that gives the film its name. Early on, the protagonist, Harry, accidentally learns that a nuclear weapon is heading towards Los Angeles, and he spends the remainder of the film attempting to find the woman, Julie, with whom he had planned to go on a first date that day. Though the couple eventually reconnects, they are unable to escape Los Angeles. At the film’s climax, the couple, trapped in a downed helicopter, attempt to console each other as they sink into the La Brea Tar Pits. Harry comforts Julie by suggesting that once they’ve been encased in tar, a direct hit will metamorphosize them, turning the lovers into diamonds. A direct nuclear strike puts them out of their misery and perhaps begins the metamorphosis of which Harry spoke. I bring this film up because it exemplifies how oil can be alternatively conceptualized. The function of the oil in Miracle Mile is to trap the young lovers, but it also transforms them into living fossils, a precondition for them to become diamonds. It is notable that the only solace Harry can provide as they await certain death is that together they will become earth itself. Whether as fossils or eventually, as diamonds, Harry and Julie are able to transcend the tragedy of their circumstances. Perhaps they will come to haunt future visitors to the pits, as so many visitors to the La Brea Tar Pits are. It is a disconcerting ending, but it is also one that simultaneously erases any distinction between “human” and “land” while also allowing the couple to survive, in some form, that most destructive fulfillment of masculinist Western scientific rationalism, the nuclear bomb.3 Perhaps this is an application of oil that ecofeminism can support.

- Plumwood, Val. “Gender, Eco-Feminism and the Environment.” Chapter. In Controversies in Environmental Sociology, edited by Robert White, 43–60. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. ↩︎

- See Adam Hanieh, Crude Capitalism: Oil, Corporate Power, and the Making of the World Market (London: Verso Books, 2024). ↩︎

- See Cohn, Carol. “Sex and Death in the Rational World of Defense Intellectuals.” Signs 12, no. 4 (1987): 687–718. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174209. ↩︎