OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

LOOKING AT NOISE, A CONVERSATION WITH BRIAN SPRINGER

THE PUNK AESTHETIC

Rachel Garfield, in her text Experimental Filmmaking and Punk, brings forth various definitions for a non-commercial, non-institutional form of moving image as seen in the poor image, the minor cinema, the avant-garde, the underground, and most importantly for her text, in punk, as a form and ethos of filmmaking.

Punk, for Garfield, is a form of film being made at the end of the post-war moment, at the high points of the Cold War and the conflict between the UK and Northern Ireland, situated in a Thatcherian United Kingdom, as social expectations in economic growth and social mobility waned, as Thatcher claimed “there is no society,” as leftist activism, as stated by Paul Gilroy, turned from anti-fascism to anti-racism.[1] Punk was made as a form that was not participating in the high/low dichotomy, a form that played out and illustrated the situated experiences from within a broken-down society but did not attempt to do anything for that society beyond what it did for those making it, engaging with it, and watching it.

The work highlighted in her book looks specifically at female filmmakers, often those left out of institutional frameworks and written histories, who saw punk as “an existential crisis.”[2] Grounding her thinking in the work of Siegfried Kracauer, who states that “[t]he position that an epoch occupies in the historical process can be determined more strikingly from an analysis of its inconspicuous surface-level expressions than from that epoch’s judgments about itself,” Garfield engages with films that find form through a different sort of expression, one that simultaneously negates both “desire and the desiring or the desired image.”[3] Following from her characterization of punk as the “valorization of the amateur, the ignorant, and the do-it-yourself,” Garfield concludes the introductory portion of her analysis with a question on what the poor image means and can do today:

But what of today? There has been a sharp increase in the interest and popularity of the punk movement and music. Today, with YouTube homemade movie stars on the one hand and the 4k intensity of cameras on the other, there is almost a fetishization of the aesthetic of the pre-digital that requires interrogation; what is the contrast between what looks like the shaky, homemade camera and the need to make under the pre-internet, lo-fi conditions of the 1980s?”[4]

For Garfield, the poor image of punk comes from its material production, one of a “pre-internet, lo-fi condition” of filmmaking. What Garfield does not engage with is noise.

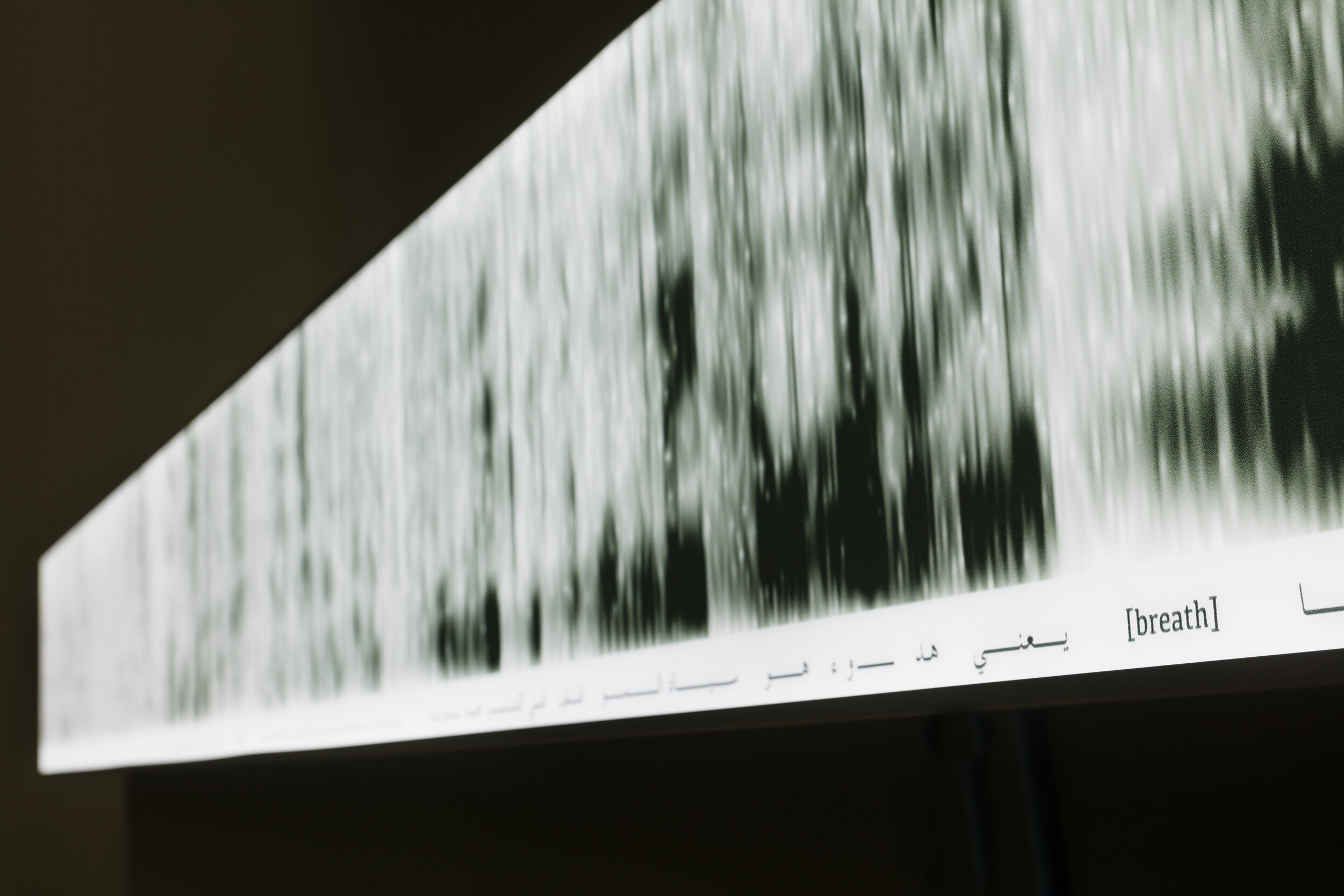

Today, the poor image through the lens of Garfield is not the aesthetic recreation, the “fetishization” of a former poor image (while such an image can be described as an alternative form of poor image). It rather can be understood in other ways, one such being in its digital iterations, as seen in Hito Steyerl’s writing. The poor image for Steyerl is

… a copy in motion. Its quality is bad, its resolution substandard. As it accelerates, it deteriorates. It is a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image, distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution….The poor image has been uploaded, downloaded, shared, reformatted, and reedited. It transforms quality into accessibility, exhibition value into cult value, films into clips, contemplation into distraction. The image is liberated from the vaults of cinemas and archives and thrust into digital uncertainty, at the expense of its own substance. The poor image tends towards abstraction; it is a visual idea in its very becoming.

…Its genealogy is dubious. Its file names are deliberately misspelled. It often defies patrimony, national culture, or indeed copyright. It is passed on as a lure, a decoy, an index, or as a reminder of its former visual self….They are the trash that washes up on the digital economies’ shores….They spread pleasure or death threats, conspiracy theories or bootlegs, resistance or stultification. Poor images show the rare, the obvious, and the unbelievable – that is, if we can still manage to decipher them.[5]

Here, the poor image, the ‘visual idea’, exists in its digital form, and in its rapid movement and repetition. In the interview that follows, we speak with a media artist thinking about the construction of the image, and who captured the image-in-motion, the image-in-between, the analog video image captured via satellite feed in the historical moment before it took on a digital form.

Brian Springer, the artist behind the 1995 documentary film Spin, embodies the do-it-yourself ethos of a filmmaker working with the circulation of images and narratives within the American conscious and subconscious, raising questions that allude to both Garfield and Steryl’s thinking around the poor image – what a poor image is, how it is made, and what it can do. Springer’s work asks us to think about the use of the unwanted image that is otherwise seen as trash, junk, or noise, and demonstrates the importance of looking at that which may seem mundane, useless, or otherwise unworthy. For Springer, the work begins in the noticing of stories that these images carry and effuse, and it is in the capturing of the seemingly unimportant, where the work lies.

INTERVIEW WITH BRIAN SPRINGER: On SPIN (1995) and THE DISAPPOINTMENT: OR, THE FORCE OF CREDULITY (2007)

“There’s a searching aspect that I enjoy about media. Someone once told me the Latin root of video means ‘to see clearly,’ and that’s what I’m trying to do.” Brian Springer, The Sky Opened Up With Answers

The following discussion with Brian Springer and Chris Hill took place on May 2, 2023 at 5:00 pm est. Springer is a media artist, whose films Spin (1995) and The Disappointment: Or, The Force of Credulity (2007), we discuss here. Spin, a film compiled of unedited, recorded television footage accessed through satellite feeds from the 1992 election year, presents the audience with the construction of television, the nuances of political speech, and with the unretractable importance of the TV personality in American society and politics. The work acts as a document of an ephemeral archive whose contents, both captured and not, continue to ripple through society with increasing strength. In the distinct visibility of the line between on and off-air, and the ways in which this line is manipulated and used, both knowingly and not, there arises another way of seeing Larry King, George Bush Sr., Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Pat Robertson, Tipper Gore and all of those who have since taken their place.

The Disappointment: Or, The Force of Credulity is a film about a nation’s relentless hunt for buried treasure, and the story of war trauma, told through a son’s desire to ask questions of his father. The film opens up and weaves together unresolved threads: a cave rumored to hold treasure, an unidentified, reptile-like artifact who acts as the film’s narrator, a mysterious rock carving, and the lost and still unfound letters of anarchist author, Kate Austin.[6] These threads converge through place, they have all passed through one plot of land in Missouri, and yet they all remain lost in some way. This diary-like film, made to exist as its own artifact, acts out a searching, telling the varied acts of looking-for, simultaneously positioning itself outside of the stories it includes. No revelations are given, no new treasure is confirmed in any form, only the echoes of the stories that we continue to hear reverberate from the cave walls.

Hill, a video curator and a film and video educator, who worked with Springer on both projects, participated in the discussion. This is an edited transcription from a recorded conversation.

Amy Poncher: Can you begin by telling us a little bit about your practice? Even though Spin and The Disappointment: Or, The Force of Credulity, are such different films, they seem to have similarities within them, they engage with media in a very intentional way. The media itself is different, but they tap into stories that are moving across each other simultaneously. I wonder if you can talk about the films more generally to begin.

Brian Springer: I have always been interested in transmission. I had played around with cell phone systems early on, when cell phones were new. There were different ways of mining my media environment through techniques and tools that might exist more in communications systems, not necessarily with video directly. I am always interested in foibles and new technologies, the new windows that open as systems try to gather information and increasingly gain control. The process of getting information opens new windows, or identifies leaks in the system, kind of inherently.

The regulatory framework for satellite transmissions was based on rail system models. The term ‘common carrier,’ also associated with the telephone, is based on railway systems, where you have a caboose, or a specific car of the train, and you could put contents into it that would not be inspected. There was privacy, provided through a legislative framework, with the state not looking through everything. And then you had satellite systems, which was what happens when you have one train arriving at 40,000 destinations at the same time. It is really a unique investigative train to delve into.

And I guess maybe with The Disappointment, it’s about having a unique window into a folk magic system practiced by a family. I do not know if these two systems are really related or not, but I guess I am just always interested in finding ephemeral archives that cut deep but disappear very easily. If someone does not record and fix a moment with a satellite dish it does not exist; and some abject aspect of the folk magic system might not get talked about for any number of reasons. That is what I think about this today and this afternoon.

AP: One of the things that I found very similar was that you were in both instances looking at something that could be seen if you looked, but most people do not. The way that you gave form to a lot of information, it is almost too much information for most people, and the way that you organize it all to make it something that we can see in video form.

BS: I don’t know if it’s too much information, as you never know how you get on top of a work. I watched and recorded feeds for one year. The satellite piece [Spin] also became a diary based on the electoral year, so it’s based on the calendar. And The Disappointment, it probably could have been much more accessible as an essay film or experimental documentary. There could have been different approaches to it. But for starters, it was low budget, so you have to say things because there’s no footage to reference something. But also now there are other people actively digging on that land, different iterations of this searching phenomenon that my family was involved in, and so I wanted to make the film kind of difficult and slightly barred for audiences in terms of getting to the narrative crux of it all. So on the one hand, with Spin, the project was based on the calendar year, and The Disappointment was based on my speculative understanding of American buried treasure practice and how that is kind of embedded in the American psyche as a foundational condition. People trying to make up a story of a nation, or the story of a place, both are inevitably all tied up with ideology and power.

AP: Yes, like in [The Disappointment] where you speak about the change in the meaning of ‘discover,’ and when you discuss the terms “‘revealed + unknown’, ‘diary + treasure’, ‘historic + fantastic’”…[7]

BS: And the uncanny, you know, like Mike Kelley’s article ‘Playing with Dead Things,’ I was playing with the uncanny as a tool, the familiar and the unfamiliar. Treasure hunting stories always open with a narrator who sees the treasure, but who’s the narrator here and what is the treasure? (laughs)

AP: When did you make the decision to make the narrator of the film the [zoomorph], as opposed to narrating from your point of view?

BS: I think it was that it just kind of made sense as I was editing for moving the footage forward in a timely manner… I was using the computer-generated voice as a placeholder; I really hadn’t decided how to deal with the voice of the narrator of the piece. And then, I was like, well I guess that kind of works.

AP: I liked it. I was curious about the narrator in terms of your choice for its voice first. Knowing it was computer-generated, that it was not you speaking, while still wondering about its aliveness. I guess it was uncanny… and then it turns to the first person…

BS: It gave me some distance to play with the material, and deal with the notion of ‘who’s this omniscient force?’…

AP: Who’s been there longer than anyone. Or maybe not….

BS: Right, right.

AP: To go back briefly and to begin with Spin, could you explain how you did it, and what the process was like for you? Specifically, to watch this footage for a year and then to make the film?

BS: I was desperately trying to grab an analog communications window before it turned fully into a digital realm. In 2000, television became digital, and before that, it was in an analog environment, and analog signal transmission was very hard to regulate. It was much freer.[8] Once things became digital, you could go to jail for appropriating footage or code. Now it’s the same as hacking a computer system, so it is much more draconian, much more serious. There was this window that opened in 1982. The idea was not to have big satellite dishes in people’s back yards, that was never the FCC or the industry’s intention. But there were these three guys. One made the electronics for the satellite receiver, and this other guy started spinning dishes out of aluminum and then there was this promoter, an aluminum siding salesman guy. And basically, [the government] couldn’t outlaw having an 8-foot parabolic dish in your back yard. In ‘82, the transmitter on satellites had about the same power as your car radio. It was a very weak signal. You’d need very large dishes to receive that signal. There was technology around ‘82 that could amplify a signal maybe 40,000 times, I think that cost around $40,000-50,000. And then all of a sudden, that system cost 800 dollars. The three men had put together a package with this so that, for example, people could watch TV in rural Oklahoma or steal HBO. During the Reagan administration there was no one watching for violations, so it was quite wide open and by ’92, because of technological changes, that window was almost shut. I had never received funding to do a project, but in ‘92 I met documentary filmmaker Kevin Rafferty and journalist James Ridgeway. They were making a film called Video Democracy, and I demo’ed some of the material I was able to record in 1990, and they saw it, and they said, “great, we’re making a film called Video Democracy,and we’d like to have satellite feeds in the film.” And so then, they were friends with Michael Moore, and Michael Moore bought my dishes, but in return for that I agreed to provide some of my footage to Rafferty and Ridgeway’s project.[9] So then as this window was closing, I was just desperate to make it work, and it was all an experiment. So, I was hunting frantically to provide them with footage and for me to document this phenomenon before it becomes less prevalent in a digital environment. It was a window that was closing and I was grabbing it before it was closed…

AP: And you knew that you could do this…

BS: Yeah, I had been reading about it since ’84, but I had never gotten access to funding to do it. For Spin, I had three satellite systems that were $2,000 each, I had to find a place to put them, wipe the snow off them on a roof in Buffalo, and work obsessively because it was time-sensitive in terms of the election that year [1992] …and in terms of phenomena that would be going away…

AP: And once you became familiar with where to look, did it become an easier matter of watching, or were you always searching?

BS: Yeah, I would try to get press schedules, try to figure out who’s in DC, who’s on the road. It was pre-internet. I didn’t have a telephone in my studio, but there was a pay phone across the street. So, you’d try to get the New York Times to see what’s going on. It was a mixture of both, I think there were 30 satellites in orbit, you start trolling, you’d see patterns develop, if someone was on CNN, they’d be on Telestar 6, and someone on CBS would be on another channel. You’d see an empty chair. You could tell by the quality of the chair if it was going to be an important guest or not an important guest. And you’d press record to capture something you thought might be interesting. It’s always kind of hit-and-miss. It was ultimately a lot of scanning, scanning and chance, and seeing some patterns but then also being surprised.

Chris Hill: I think the other thing that is very interesting, is that the process is like fishing, there are plenty of things that get away because you didn’t press record. You couldn’t possibly have afforded the videotape to record everything, you’re always gambling as to whether something might evolve, and you want to hit the record button before the gem actually gets uttered from someone’s mouth. It’s a very performative process for the person trying to capture an interesting feed; it’s like having to anticipate a significant performance.

BS: Yeah, and it’s not a complete data set, you’re just sampling. Like the Larry Agran footage in Spin, I had just never seen someone treated that bad. His chair is out in the hallways, the guy is pulling money out to pay for makeup that the network didn’t provide. I didn’t know who Larry Agran was, didn’t know he was running for president. It was a feed for Nightline, so I just recorded it because I’d never seen anyone treated so badly. It’s a chance operation, it’s a narrow sampling, it’s not a complete set of all the channels.

AP: The Larry Agran footage was shocking, the way they would crop him out, and the scene with all of the candidates waiting to go on air, and then you hear his voice faintly in the background, and the anchor says ‘we’re going to wait for the man to be quiet.’ But seeing the footage, and then seeing how these seemingly minor moments made it so that he could not run for president because he was not in the literal frame, was …

BS: Yeah, you feel that frame’s contested, right? It’s the same as the camera swinging this way or that way during the feed when people are having make up put on. But you know, the process was— get up at 6 am, see who’s speaking to the morning shows, and then wait until about midnight till the late-night shows and see what happens. And then you gotta log it at some point, so that’s a pain…

AP: You knew that you were covering the election, but how much footage did you end up recording, and how did you decide what to include and what not to include?

BS: I think I recorded 600 hours and it took about 15 months to log that. And there was the phenomenon of the whole control system in general. Why it exists with television is because there’s a producer in NY who wants to make sure the guest is alive, that they’re there, that the microphone is working, the lights are working. Everyone wants control. It’s about the whole process of making the live moment as dead as possible. At times, this contempt for public debate and public discussion became kind of the filter and always that question of who’s in the frame, who’s not, becomes important. I liked the collision between the on-air and the off-air personality, the kind of contempt for public discussion was one of my filters.

AP: Public discussion and the live moment are so important, I’m thinking about their relationship to the ephemeral, and to illusion, in this case, and how these concepts come together…

BS: There’s this notion of revealing secrets as when people talk off camera, and it kind of has certain clues to authenticity in a different space, or perhaps this is closer to how the person feels.

It’s also an odd experience performatively. It’s 6 am in New Hampshire, and I’m watching feeds at 6 am in Buffalo. You get a sense of people’s health, you start knowing the candidates in their off-air space, you can tell when they’re getting a cold. You almost know when they’re going to go up and down in the polls a couple of days before it’s publicly announced because you see they’re sick, and then two days later you find out they’re in trouble. So that was an odd environment. They’re also being talked to through a phone line, through an earpiece, an IFB. Gosh, I just really wanted to have a cell phone because they were giving out the numbers. I thought, ah shit, I’ll just interview Bill Clinton, here’s the number. So, then it becomes weird because you’re in this privileged space of being in the networks’ system, and it’s like, oh, well what can I do here? (laughs) So you feel like you’re in the system of power, not that I felt like I had power, but it was an odd experience of being in the patch bay of the corporation as they went about their business.

AP: Do you know if there were other people doing a similar thing? Because in the film we see that the campaigns were doing this, but do you know about anyone else working on their own?

BS: Yeah, the campaigns knew. It was a Friday afternoon, and I had to take off 3-4 hours to go somewhere, and I had a friend of mine come over, and it was the Bill Clinton feed where he’s complaining about an incident with Jesse Jackson…I probably should have put this in the film but I just couldn’t figure out how to do this because I missed the feed, the person recorded it partially but they didn’t stay with it, and it was a big deal. You know there are different understandings of technology, Bill Clinton was more culturally savvy—he had had an El Camino with a shell on it, a stereo system, a shag rug, and George Bush Sr. had a minimal relationship to technology. There is a different type of savvy and awareness of technology among the candidates. Clinton used that off-air moment. I can imagine that Stephanopoulos [a Clinton advisor at that time] and that team actually had him blow-up off-camera at Jesse Jackson, as a way to distance himself from the black vote, [there had been an incident with hip hop artist Sister Souljah], and then that became the news story for about 8 hours…

CH: And a television technician recorded it.

BS: Yeah, the stations got the feed, and they used that outburst, and it drew a wedge between Jackson and Clinton which may have been needed for white voters to be more comfortable with Clinton…So I thought the Clinton campaign used satellite feeds as a stage, whereas other candidates weren’t so aware. …And in response to your question, no one really wants to do surveillance, who really wants to spend all day recording and going back and transcribing. I think Harry Shearer had a big dish in his house in Santa Monica, and he did an installation for Barneys in NY. It was a silent debate, so it was a satellite feed of all of the different candidates not saying anything. It was mostly about being in that weird teleport environment, but there wasn’t anyone else doing it like I was as far as I know… The feeds had been wide open, it was fairly amazing, especially during the Reagan presidency. That’s when I really wished I could have recorded feeds.

CH: There were commercial things on the satellite too, Microsoft would have an event where all of the salesmen would get together and they would use satellite to join groups in different parts of the country, and the military used it to do things…

BS: Yeah, so you would get other weird programing, I watched a live FEMA training exercise for a nuclear meltdown at a nuclear plant in Tennessee, where tv employees acted as members of the press. The plot of the exercise was that a tornado had blocked their water intake, and there was a partial melt down, and radiation tablets had been dispersed. Someone came out and talked about how farmers would get reimbursement for dead animals. There was always that other industrial part of satellite communication and for sure that was very interesting.

AP: And did you record any of that?

BS: Oh yeah I recorded tons of that, I loved that stuff. I kept recording for a couple of years after Spin, when all I did was record corporate TV. For the life of me, I didn’t have the stamina to stay awake long enough to try to log it because it’s so painfully boring. You know when I was first starting the project, I wanted to have the actual commercial that was playing when the speakers were off-air, and I wanted to use the corporate tv that was related to the commercial, with the idea that it would keep spinning around.

AP: And you still have all of those tapes?

BS: Yeah, I’ve got all of those VHS tapes, and will eventually digitize them and put them onto Archive.org. But yeah, military training, police training, are very odd moments to watch or record. I think it was in 1998, there was an Israeli TV technician, because people do steal footage, and he was in fact doing what I was doing, looking for deviant behavior within the feed lexicon. So he hit record, and it was a weapons missile testing of a Raytheon missile system for the Israeli military. They were talking shop for three days, and that was recorded with a small dish. The guy ultimately erased the footage, you know that is sensitive information. But even with encryption, things always go wrong…the encryption key isn’t right, you know, Frank took the day off and the key doesn’t work, it’s a big day for the weapons system test, and the CEO is in Montana that weekend, and he rents a satellite dish and there’s a problem with the decoder, and the guy at headquarters can’t figure out how to make it work for the CEO in Montana, so they just don’t encode it. Because who’s going to look through the electronic trash? That’s the idea, that it will get buried in noise. So these abnormalities, I imagine they are still occurring, somewhat….

AP: Are you following this now in the same way?

BS: I don’t have any dishes so I don’t follow it. The one thing that was really interesting is an old Inmarsat satellite. It is really weak and has a wobble orbit, you need a thirty-foot dish to get it. It’s interesting because there were all these U.S. military missiles being used in Iraq with video cameras on them, a lot of drone strikes, and they moved a lot of footage over those satellites. But that type of footage was moving around in the digital underground in Europe, the obvious satellite enthusiasts. In terms of spectrum analysis of satellites, I stopped looking after 2010…

AP: This makes me think about your earlier comment on noise, which is one of the things that I thought connected the two films as well in some way. Could you speak about your thoughts on noise?

BS: Hmmm, that’s interesting. I could think of metaphors…I’m trying to think of linkages of the two projects, they are quite different, one is based in time and the other is based in geography. Well, in terms of noise, we can talk about spiritualism [and its connection with The Disappointment]. This is not a deep, well-researched topic of mine but, you know, let’s say spiritualism is the vocalizing of what the spirit is telling you. As far as I understand it, as spiritualism became more commodified [as in the practice of spiritualism and readings], its central tenet became validation that there was life beyond, and that awareness would be delivered by connecting with a spirit that had a relationship to the person getting the reading, giving people comfort that there was life after death. But there can also be connections with spirits that are wandering and not directly connected with anyone living at the reading. You could have a group of people, and there could be a spiritualist there, and they would sense a spirit, and talk about that spirit, and the spirit was usually described as being in a place of darkness wanting to go to light, and there would be no one in the group who knew this person/spirit.

CH: It wasn’t about a person trying to connect with their dead parent or a specific person.

BS: So I guess you wanted me to talk about noise, so I think of noise and spiritualism, there’s different types of folk magic practices, and I’m considering spiritualism as a kind of folk magic practice, and some of them are very much based in noise, they are highly experimental, somewhat dangerous, right. I would say if you move into certain visions, they could be very ungrounded, very open, where one’s imagination could literally run wild, and that’s the most noisy kind of spirit. And while this type of spiritual practice is not really discussed in The Disappointment, that’s the kind of spiritualism or folk practice my father was interested in.

AP: How did The Disappointment come to be?

BS: I just gathered material about the farm and its history, and it was such a weird story and I got used to telling it to people in the 80’s and 90’s. I thought no one’s ever going to believe it, but I was gathering material so it wouldn’t get lost, shooting a little bit at the cave where my father continued to dig….

CH: And you wanted your father to stop going down into the cave by himself ultimately.

BS: Yeah, my father was having heart issues and working alone, and my mother was very concerned he would die, and she would feel guilty, so I was trying to make an artifact for him. That was what I was doing initially. And then he died, so I thought, okay, this can go a different direction.

AP: Speaking of artifacts, could you begin by talking about the rock with the symbol a little bit?[10] This element of the extreme in stories of origin seems to be a common thread in the work.

BS: So post-contact, post-Columbus, rock art was a practice. How long would it take you to carve that piece of rock? An hour and a half, maybe two hours [if it was soft like limestone]. So now we have an artifact. There are different narrative interpretations over different periods of time about what these symbols carved into the limestone meant in this part of Missouri. One interpretation was set in the burnt over districts along the Kansas/Missouri border in the mid 19th century. Kansas was being populated by people from the northeast who were anti-slavery. People in Missouri were pro-slavery, and along the Kansas/Missouri border there were paramilitary groups, called bushwhackers from Missouri. It was very violent. The central burn district was a 5 county area on the border of Missouri and Kansas, where every free standing structure was burnt to the ground one year just before winter. So it had been a very violent and very dangerous place to travel the roads. One theory about the meaning of the rock carvings was that these symbols were related to navigating these country roads so you wouldn’t get killed. That’s one notion. These rock carvings are like graffiti, and academically it’s quite abject, no one really seems to want to deal with it.

CH: And there’s another one interpretation, a very mundane version, that there was a mill nearby, and people would bring grain to get ground at the mill, and they’d have to wait two days, and so this was the graffiti they made. There are limestone caves throughout this region, and the stone on the top of the surface is also limestone, which is soft, so people were waiting to have their grain milled and carving that soft stone to pass the time. Or the markings could have been made by Native Americans who had lived in the areas and maybe lived in and used the caves.

BS: Some people theorized that there were multiple similar glyphs [rock carvings] that were interconnected, so if we could have found three of them and worked with some of the angles (indicated by graphic elements like arrows, etc) we could have speculated about what kind of navigation system these may have been ….

AP: It’s interesting because with this symbol, with Kate Austin’s lost letters that were never found, and the zoomorph [large stone carving apparently found on the farm], all these things deliver no answers to the questions that they raise. I don’t know if that was your intention…

BS: I started out trying to find Kate’s letters, the meaning of the rock glyph, and the origin of the zoomorph, but at some point I recognized that these mysteries were going to remain elusive. So then yeah, I had them rub up against each other. And I think for people who have gone through war trauma, these objects open up another universe. One guy interviewed in my film, you know, he served in the navy in World War II, pretty rough action. He’s convinced that there was a ship full of Spanish treasure that was brought up the Mississippi, and then the Missouri River, and it wound up here on this farm. He said, “I was staring at the rock art, it was 8 am and a second later it was 8 pm.” What is this relationship between trauma and abstract or mysterious spaces, these places that have uncharted histories…? Is there a need for the person who has experienced trauma to dissociate, and do these rock glyphs suggest that something special or unexplainable happened here? And as such, do they function as triggers for the dissociation?

People can speculate about carved rock glyph as graffiti created near the mill site or maps connected somehow with Spanish treasure. Also more recently, over the last generation in this region, descendants of Germans [original European settlers] have been being replaced in the work force by people from Mexico and Central America. These Latino workers had become the number one immigrant group in the region but they did not have a strong visible presence as they were working in agriculture and slaughter houses. So this type of displacement, accompanied by the rise of rightwing talk radio, fed a certain type of anxiety that influenced and shaped the stories about the buried treasure. For example, there was talk that the treasure would soon come out of the ground so that the south could rise again. There are different sociological projections over time that feed these treasure hunting stories. There was also True Lost magazine where the treasure story about this area first appeared and that attracted people’s attention. My thing was to always conjure it up as an anarchist treasure marking.

CH: But all of those stories also function as a kind of noise, that you and your family had to work through.

BS: Yeah, it’s nothing but noise. There is no way to figure out how to place these things because these legends point in so many different directions. The one thing I can say is that when my father dug down the shaft into the cave on the Austin farm, it was full of dirt, no one had been down there for quite some time. But on the rock walls of the shaft there were drawings, and a carved map of the cave system. So someone had been down there at one point many years ago. But yeah, pretty noisy…

CH: And then the Austin family, Kate’s letters, you thought that maybe they do exist someplace.

BS: A researcher from University of California came out to the Austin farm, and I remember seeing him when I was a kid. He came out to try to place Kate Austin in the moment. So when I was down there hanging out, working on The Disappointment, I kept trying to talk to the relatives. Someone had a trunk, but they didn’t have time to look. There were lots of different stories about what might have happened to the letters. And the academic article on Kate Austin is quite good, we have the published articles. The Austin farmhouse was set up so there were no curtains and no rugs, dinner was spartan, minimal, everything was organized to give her three hours a day to write. The whole family including the husband, contributed to a non-domestic environment, in contrast to the tradition would be for the wife to do these things. They tried to free her. She wrote, and many articles were published in Europe and the US. She had a real life that’s on the record. She was an anarchist author who died young. So, I had a pretty good sense of what she was about.

AP: I wanted to ask about this, going back to this concept of discovery, there is an element of you discovering things as you go, and yet it aligns more closely with ‘the reading of the diary’ and ‘revealing personal secrets publicly,’ as opposed to a ‘gaining insight or knowledge of the unknown.’ There is the very present acceptance of not knowing in the film. Can you speak more about how this relates to your recognition of the film as a diary film?

BS: I was curious about why my parents acted that way, were so dedicated to treasure hunting– that was really the initial question. I was reading about the uncanny, and thinking about the everyday, and started phoning relatives, saying did you know about CW [Springer’s father], what did you think about all this? I called my uncle, and he said, oh yeah, your dad came back from the war [in Korea] and he sat in the living room for three months, he didn’t move. No one had told me that. And then there was the story of the napalm [that CW saw being dropped by the Americans on the Korean soldiers after he, as a forward scout, had called in their locations], but perhaps because I was the youngest child, no one had told me that story either. Then understanding the horror that he witnessed as a soldier and getting a sense of his war experience, and you see it doubled up in the diary [of the Spaniard that is featured in the film who witnessed the massacre of his Native American companions], so to me it made sense.[11] The story told through my mother’s automatic writing really seemed to be a repressed retelling of my father’s war experience. The spirit [of the Spanish priest] said he couldn’t be free until his diary was found and acknowledged by the church. It’s a story about being caught between family, church and state. My father’s military experience would have condemned him to hell for being a mass murderer, but then, returning to civilian life, he was coming back and having to go to church. For him, on a deep level, none of it made sense, it just didn’t add up.

AP: And was this a common experience for war veterans?

BS: I talked to someone who specialized in war trauma, and they thought it was a perfect example of what a family’s experience is. It made sense to me. These folk magic systems are designed as theatre, sometimes it’s therapeutic for the trauma and sometimes it’s not. And I think about my mother’s performance and re-performance of the spirit of the Spanish priest in her automatic writings. She invented this narrative that would be meaningful to my father so he didn’t become an alcoholic or hurt himself or hurt us, or perhaps just to be in the playful moment…

CH: And your mother is a very sweet person, she’s very focused in the present…so you can see this being a gift to the family. It’s likely she didn’t do this consciously…The whole family experienced her automatic writing when her hand would suddenly start shaking at the dinner table. They’d take the fork out of her hand and put a pencil in her hand and she’d do the automatic writing.

BS: It happened a couple of times a week. There was a lot of writing going on at one point.

CH: And she saved the many pages of her automatic writing. She saw these communications as important.

BS: In researching for The Disappointment I had also attempted to find out who had made the zoomorph, that according to various accounts had been found on or near the Austin farm in the early to mid-1800s. The landscape in this part of the country was marked by hundreds of mounds that we understand now to have been part of a pre-contact Native American mound-building culture [extending throughout the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys] but in the 19th century no one knew who had built the mounds. Some appeared to be burial mounds and some contained stunning artifacts from distant parts of North America. For example, there were dozens of these mounds constructed where the city of St. Louis stands today, and St. Louis was once known as Mound City. The Trail of Tears [1830-1850] also passed through this part of the country, where Native Americans, forcibly displaced by the U.S. government from the Appalachian region, were marched to Indian Territory in the Great Plains, and thousands died. Undoubtedly Native American artifacts were abandoned or lost along the way. Perhaps the inspiration for objects like the zoomorph were these mysterious artifacts found in the mounds or abandoned along the Trail of Tears. However these 19th century artifacts like the zoomorph were likely created essentially as curiosities or entertainment to be displayed at fairs and such. One could consider these 19th century fairs with their curiosities as the cable TV shows of that time, traveling shows that attracted large audiences.

This film maps a history of the displaced, unnamed, unspoken about. The zoomorph, the large stone sculpture in the film, is a hoax artifact. However it remains a fascinating composite animal form that was made by a skilled stone sculptor sometime in the 19th century. But its ambiguous identity is also inflected by the culture of Native Americans being devalued and disparaged by the European settler society in the 19th century. Today the anthropologists consulted didn’t want to speculate about who had made it because they don’t know the precise geological context [location, depth, etc] where it was originally found and there’s no other artifact quite like it to compare it to. The people digging on the Austin farm, where it was supposed to have been originally found, thought the zoomorph, together with the surface limestone rock carvings, were evidence that important events had happened on the farm.

AP: In thinking about so-called origins in America, the hoax, and early forms of media and entertainment, and where we are today, I have one more question…I’m going to jump back to Spin to bring us to today. How has that film and your thoughts about it evolved over time? Do you still think about the project, especially around election years? And how are you thinking about these ideas now, around media and art specifically.

BS: I guess, with fascism and Trump being front and center and this post-truth America, it starts to bring up profound issues around notions of public and private, what is in the frame and what pressures those decisions. I don’t know what most people’s relationship is to the constructedness of a media image, but I guess for me… it was important at that time to use the satellite feeds as a way to expose what was happening behind the curtain of the television media stage for a general public. I thought of Spin as one television viewer sharing information about how television is constructed with other television viewers. One major component of Spin was the feeds of the unrest in Los Angeles [1992] after the verdict in the first trial of the police involved in the Rodney King beating. The documentation of that beating was recorded by a citizen with a camcorder, then a new type of consumer video equipment. We are aware of citizens now being mobilized to use their iPhones as witnessing devices to document police brutality, and the internet has become a distribution system for citizen’s media. Spin is an open system where I’m sampling a spectrum. If I were to do something now I would be more interested in a closed system, that is where you have the entire system, that would be interesting.

CH: One other thing, when you were working on Spin, because you were talking about this public and private space and this disregard for the audience, the other thing you were doing at that time, is that you were trying to get public-access television started in Buffalo.[12] You were interested in citizens becoming more media literate and using public access cable at the time. You were on the city’s cable committee, and there was a diverse group of people, artists but also people from non-profits, churches, and neighborhoods across the city, that you were a part of, all trying to get cable access active again. Brian’s own artwork was certainly a very particular practice, but there was also this other way you were working with various groups in the city to accomplish something related.

BS: Yeah, it’s all about media constructedness, and wanting average citizens to be aware of that, not just people working with media art. I remember when camcorders first came out and there would be a shop window with a camera on a tripod pointed out onto the streets and there would be a tv there, and people would walk by and all of a sudden they were inside the frame, it was fairly radical. At that time I was so tired of the mannered constructions of broadcast television, its pacing, its music, its graphics, everything processed and controlled until it was kind of dead. It was delightful to see things outside the network frame like this, alive.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Rachel Garfield, Experimental Filmmaking and Punk: Feminist Audio Visual Culture in the 1970s and 1980s (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021), 8.

[2] Ibid., 12.

[3] Ibid., 9-10.

[4] Ibid., 13.

[5] Hito Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012), 32.

[6] The film’s name comes from the earliest American ballad-opera from 1767, which was a satire on the colonial crazes of treasure hunting and spiritism. The inclusion of Kate Austin in the film is “a possible signpost to another future, outside the nightmare of imperial war and domestic expropriation from which millions of credulous Americans are now struggling to wake up in disbelief,” wrote Brian Holmes. For further, see Brian Holmes, “Decipher the future: Experimental work in mobile territories,” Continental Drift (2009).

[7] Narration from The Disappointment – “Before Columbus, you would call someone a discoverer if they read your private diary publicly. After Columbus, you would be called a discoverer if you gained insight or knowledge of the unknown. That is what is so vexing for the Springers, they are both types of discoverers because they are looking for two things, the revealed and the unknown, the history and fantastic, a diary and a treasure” (Brian Springer, The Disappointment; Or, The Force of Credulity, 5:40- 6:20)

[8] In 1998, President Clinton signed the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which imposed both civil and criminal penalties. For further see, https://www.copyright.gov/legislation/dmca.pdf.

[9] This film was renamed and released as Feed (1992).

[10] There is a limestone rock with a symbol on it in the film. Springer’s unfruitful attempt to find out the symbol’s meaning drives a large portion of the narrative.

[11] Brian’s mother wrote letters through automatic writing, also called psychography. In the film we see that the letters were from the diary of the Spaniard who had left his gold in the cave in the 1700’s. C.W. followed these letters in his search.

[12] Public-access cable TV is a non-commercial, community-access form of television where the public can create content for television programming and have access to local cable channels.

REFERENCES:

Garfield, Rachel. Experimental Filmmaking and Punk: Feminist Audio Visual Culture in the 1970s and 1980s. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021.

Holmes, Brian. “Decipher The Future: Experimental work in mobile territories.” Continental Drift (2009): https://brianholmes.wordpress.com/2009/09/06/decipher-the-future/.

Springer, Brian. Director. The Disappointment; Or, The Force of Credulity. 2007.

Springer, Brian. Director. Spin. 1995.

Steyerl, Hito. The Wretched of the Screen. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012.