OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Locating the Feminine in Male-dominated Social scenes

In preparation for Robeson Taj Frazier’s upcoming WHAP! Lecture titled “When the East is in the House: Streetwear and the Lure of Global Youth Culture in China” CalArts students were provided two readings, one of which was a section from Yuniya Kawamura’s book Sneakers: Fashion, Gender, and Subculture (2016). In the second chapter of the book, “Sneakers as Subculture: Emerging from Underground to Upperground,” the subcultural elements of sneaker culture and its popularity are posited as “emerging” into the mainstream. Here Kawamura traces the trajectory of sneaker, hip hop, and streetwear subculture(s)— if one is convinced that they indeed retain a subcultural status— to its newer manifestations today, characterized by a “transcending” of the race and class categories from which they originated, a diffusion of earlier social or political attitudes, and a distinctively “male” phenomenon (Kawamura 2016: 105).

Kawamura’s study focuses on the male, referring to sneakerheads exclusively as ‘boys’ and ‘men,’ and he suggests this narrow focus is the result of subcultural landscape itself. He indicates than in this “comeback” of sneaker enthusiasm, the absence of women [from his account] has to do with the men who dominate the scene excluding young women from this community, so as to make sure there is minimal association with the feminine in their style of dress. He draws this dynamic further into tension, concluding: “In today’s postmodern age, categorical differences between male affair and female affair is disappearing. The sneaker enthusiasts are not invading into the female domain, but rather, they are producing their own fashion domain as something uniquely masculine” (Kawamura 2016: 105). The impression given by these concluding remarks is that rather than actively avoiding the role of women in sneaker-wearing-fandom, Kawamura is simply following the lead of the men who dominate the sneakerhead scene. Puzzled by this, I would like to draw out a few observations about Kawamura’s account of feminine absence, as well the study of subcultures more broadly, which will lead me to briefly tracing of some of women’s roles in and contributions to street wear fashion, hip hop, and sneaker-wearing through today.

As McRobbie and Garber noted in their text “Girls and Subcultures” (1977) from the book Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Postwar Britain (Cultural Studies Birmingham) edited by Stuart Hall, the “leaving out” of young women from sociological studies on subcultures has been a long-standing norm within the discipline. They write: “When girls do appear, it is either in ways which uncritically reinforce the stereotypical image of women with which we are now so familiar… for example, Fyvels’s reference, in his study of teddy boys [Fyvel 1961], to ‘dumb, passive teenage girls, crudely painted’… or else they are fleetingly or marginally presented” (McRobbie and Garber 1977: 105). The authors, seeking to make sense of this invisibility, ask key questions that help to interrogate how and why these accounts (often centered around girl’s sexual desirability alone) come to be — when it is clear that there is indeed a feminine presence in these subcultures, regardless of whether or in what way they are acknowledged.

Thus, “Is this simply a typically dismissive treatment of girls reflecting the natural rapport between a masculine researcher and his male respondents? Or is it that the researcher who is, after all, studying the motor-bike boys, finds it difficult not to take the boy’s attitudes to and evaluation of the girls, seriously?” (McRobbie and Garber 1977: 106). In the examples they consult, it is clear that feminine invisibility is actually better characterized as erasure from the dominant narratives of UK subcultures, or perhaps the ‘scenes’ themselves. McRobbie and Garber’s methodological inquiry, which later guides their study of motor-bike girls, mod girls, and hippies, shifts the attention from the question of whether girls and women are really absent from subcultures (as the studies would suggest), toward how and at what stage the research carried out might render them invisible. It seems equally prudent to apply this same query to Kawamura’s work, especially in light of the long-standing tradition of women pioneering hip hop fashion and trends throughout the eighties, nineties and early 200s, as well their continued presence in the current, if distinct sneaker scene.

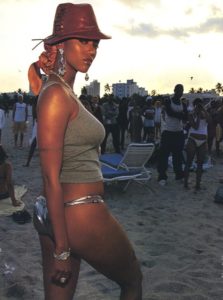

There is, of course, a marked difference between the trajectory of UK’s post-war subcultures and the rise of hip hop in the United States, which was incredibly popular and became quickly commercialized just a few years after its start in the late 70s in NYC. In many ways, hip hop and the culture surrounding it did not resist its absorption into the mainstream and capitalist markets, unlike the attitudes of other major subcultures in the US, like punk. And most notably, women were involved and often the face of much of its cultural output throughout its rise after the first popular MCs. When it came to fashion, rapping, and sneakers, rather than try to “feminize” these touchstones of hip hop culture, young women both on the streets and in mainstream media expressed themselves through the same ‘masculine’ styles as men.

Female desirability, in these cases, had as much to do with keeping up with the boys and looking stylish, as it did their sexual desirability or femininity. These qualities are not so separate, but rather wrapped up in one another… the feminine expressing itself with the same cultural markers otherwise dubbed “masculine”. This dynamic was integral to all of the (mainstream) artists like TLC, Lil Kim, or Aaliyah, to lesser known female MCs throughout. Similar dynamics can be seen in other subcultures oriented around rock or electronic music, where again young women are able to express themselves through the same contemporary lexicons as men, with the same touch of individualism that members of a subculture, regardless of gender, could bring to their personal expression. Today, hip hop culture is not just a part of American cultural memory, nor a succession of waves, but is completely integral to what became and continues to shape the “popular.”

Women & Streetwear

Even if streetwear and contemporary sneaker scenes are male-dominated, there is no way that women are not in some way involved or integral to its expression. Not only is there mutual sneaker appreciation between all people in contemporary society, given their colossal ubiquity, but also operating on the presumed heterosexuality of a significant portion of today’s “hypebeasts,” there are probably some ladies in the sneaker game who share the same interests and styles and distinguish themselves accordingly. Kawamura’s chapter includes many references to hype-beast culture (without referring to it as such) like collecting sneakers of certain models and brands for, well, the hype.

The term hypebeast, used in jest or with tones of critique for its commercialism and perceived shallowness, usually references young men, and has become increasingly popular / less looked down upon in recent years. It is the name sake of a sneaker-blog turned online culture/fashion publication HYPEBEAST, which features a “footwear” section and describes itself as “for men”. Similarly, the magazine Complex, a sneaker and pop-culture oriented magazine and online publication reflects current trends and hip-hop oriented content. Their popular video series ____ goes sneaker shopping with Complex on YouTube features popular celebrities and many rappers, certainly includes more men than women, but features at least a few relevant women each season.

Unlike the usual hip-hop oriented people they bring on to the series, a guest spot by model Bella Hadid in 2017 blew up online for her perceived disingenuous posturing in an attempt to be ‘cool’, and perhaps over-inflating her appreciation of sneakers. This meme-worthy moment is preceded by her remarks on how sneakers are suited for both men and women, describing them as “dope” and also “sexy” in reference to how she looks / feels in her favorite pair. Hadid also suggests that sneakers are the first thing she looks for in a man, leading to her famous statement that if a hypothetical “homeboy” wears a particular type of sneaker he could “like, get it.” Her remarks not only show the way in which women and men might discriminate mutual desirability according to their sneakers and fashion tastes (if we take anything from this video seriously), but her appearance in the series also suggests an emergence beyond “the upperground” from the already mainstream, through the popularization of off-duty model’s fashion, into elite connotations.

But before the meteoric rise of hypebeasts and the collecting of high-end sneakers and ‘streetwear’ labels, women were rocking and influencing streetwear styles that were not only mainstream, but continued to influence fashion as trends are recycled. The new Netflix series Next in Fashion featured a contestant known as Kiki Kitty who has had a long career in women’s streetwear. Her career highlights include designing for FUBU women’s streetwear line, Roca Wear, Sean John, and House of Dereon – all popular and celebrity affiliated streetwear / hip hop brands in the 90s and early 2000s. In the series intro Kiki is regarded as the “grande dame of streetwear” and was eliminated after a controversial streetwear episode. A failed relaunch of the famous womenswear line Baby Phat headed by Kimora Lee Simmons [and a lingering revitalization of 2000s fashion] has reminded fans of Y2K fashions of some of the previous iterations of streetwear, as well as a fashion scene that looked markedly different from that of the 1990s or today. Baby Phat was famous for what today we might call “inclusivity” by marketing itself to women of color through hip hop aesthetics, Kimora Lee’s own mixed heritage, and their sizes which included a larger range for curvier and bigger women. And the looks were delightfully 00s. The exaggerated femininity of their designs mixed with materials and fabrics you would see on a rich-looking man like leather of fur was meant to emulate video girls and celebrate / augment their desirability. While Baby Phat was not putting out sneakers or menswear looks, through its attachments to Russel Simmons and hip hop royalty, it is decidedly streetwear – and was at one point valued at over 1 billion dollars.

Rapper Lil Kim walking the 2003 Baby Phat runway show.

Model Tyra Banks wearing a Baby Phat hat featuring their famous cat logo.

Although it is quite likely Kawamura is aware of the fashions of the 90s and 00s as being influential, he seems to maintain a myopic view regarding men and sneaker-culture as only ever defining itself against women, and never with and even because of them. As we observed through the contributions of McRobbie and Garber’s methodological questions, which shaped their analysis of girls in subculture, feminine absence is not “true” but rather is imposed either in reality through exclusion or in the narratives and studies that have shaped subcultural studies historically. Kawamura cites the CCS Birmingham, but he does not seem to be aware of the contributions of McRobbie and Garber, or at least does not align with their perspective in his work. With their contributions, and a bit of healthy skepticism on our part as readers, we are reminded that sociological studies are always potentially wrapped up in the bias of a researcher, the subjects, or other influences that may not be wholly representing complex social dynamics.

However, in this case, the issue is not so complex. Women have been at the forefront of the hip hop and fashion scene through all of the stages of development that Kawamura covers in the chapter. These scenes have been ‘mainstream’ for decades now, and the women that helped to make it palatable and appealing to the masses continue to be celebrated as cultural icons – and rightfully so.

Works Cited:

Kawamura, Yuniya. 2016. “Sneakers as a Subculture: Emerging from Underground to Upperground” in Sneakers: Fashion, Gender, and Subculture. Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK.

Angela McRobbie and Jenny Garber. 1977. “Girls and Subcultures” in Resistance through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-war Britain. Edited by Stuart Hall. 2nd edition. Routledge: London, UK (2007).