OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

How to Avoid Kettling: Line Dance as Protest

On December 11th, 2020, Calvin L. Warren will give a public lecture “Being Blacked Out/Blacking Out Being: Nihilistic Considerations” as part of the West Hollywood Aesthetics and Politics (WHAP!) series, with respondent Linette Park. Warren is an Associate Professor of African American Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and the author of Ontological Terror: Blackness, Nihilism, and Emancipation (2018) published by Duke University Press. He is currently working on a second project, Onticide: Essays on Black Nihilism and Sexuality. The Fall 2020 Lecture Series, “Black Out: On the Surveillance of Blackness,” is presented by the CalArts School of Critical Studies and the West Hollywood Public Library. The lecture will be held virtually at 4:30 PST and can be viewed live here. In the following, I turn to Warren’s “Black Mysticism: Fred Moten’s Phenomenology of (Black) Spirit” (2017) to consider political ontologies of popular line dance as a protest tactic, looking at examples between May 28, 2020 and July 23, 2020.

Attending the Black Lives Matter (BLM) Pasadena’s Juneteenth town hall and march this past summer, I witnessed my first example of line dance as a protest method. Stopping at an intersection, protest organizers played music and led people in line dances including the Wobble and Cha Cha Slide Part II. Considering the contextual history of dance, party, and celebration as alternative protest tactics alongside marches, town halls, and forums, I am led to ask: How does line dance disrupt the linearity of protest tactics? For instance, does line dance re-orient a march moving down a street in one direction, or dispersing the constricting lines of a kettle? And how might this disruption alter political ontology?

THIS IS SOMETHING NEW:

INTRODUCTION TO LINE DANCE

Line dance consists of a group of people performing synchronized, repetitive, and sequenced choreography often in rows or lines. Dancers usually face the same direction, known as walls. Various line dances consist of a different number of walls that specify the direction the dancers face at any given time in the choreographic sequence. For example, the Cha Cha Slide Part II by D.J. Casper is a four-wall line dance because the sequence ends by facing the wall 90 degrees to the right or left of the sequence’s beginning wall before repeating again. In contrast, the YMCA is a one-wall line dance because dancers do not change the direction they face. [Action Suggestion: Before continuing to read, listen and dance to the Cha Cha Slide Part II. Ask people around you to join, and pay particular attention to your surrounding walls. If you are able, dance in an outdoor space.]

The history of the Cha Cha Slide Part II as first an aerobic exercise then staple at weddings, proms, birthdays, bat mitzvahs, etc. points to a longer history of line dance as a collective rhythmic exercise in party, celebration, and family. A podcast episode of “The Nod” (embedded below) further details these genealogies of the Cha Cha Slide Part II within deeper generational traditions in blackness and black performance. In the podcast, D.J. Casper speaks about the accessible and egalitarian effects of his lyrics containing dance instructions. D.J. Casper describes, “All you have to do is listen and I will tell you how to do the dance.” This instructional character of Casper’s lyrics (Let’s go to work, To the left, Take it back now y’all; Freeze, everybody clap your hands; Hands on your knees, hands on your knees; Reverse, reverse; Etc…) mirrors the call-and-response format of protest chants during the 2020 BLM demonstrations that instruct a physical action. For instance, a common chant “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” is accompanied by raising hands in the air; or the chant “Take a knee! Take a knee!” signals for everyone to kneel. This instructional quality allows for an accessible collective action, however also a possible appropriation. When the police kneels or a white protester chants “I can’t breathe,” political ontology changes of these words/actions change depending on both their genealogies and who enacts them. Coming from a history of black dance, party, and celebration: how do the political ontologies of line dance change in the context of protest tactics alongside marches, town halls, and forums?

LETS GO TO WORK:

DIRECTION & INSTRUCTION

The 11Alive report, “National Guard troops dance in the streets with protesters,” recorded National Guard troops dancing with protesters to the Cha Cha Slide Part II. Watching the video, the instructional and directional character of line dance’s 4-wall choreography appears to reorient who is at the “front” or leading the gathered crowd. To join the line dance, the troops disassembled their military line. The putative authority figures give up a hierarchical positioning of being at the “front” of the line to join a more public line. The reporter narrating the scene, Hope Ford, describes the troops “not getting the dance yet, but they’re trying.” The troops here seem to forfeit some sort of power by allowing themselves to be led by protesters and D.J. Casper’s instructions.

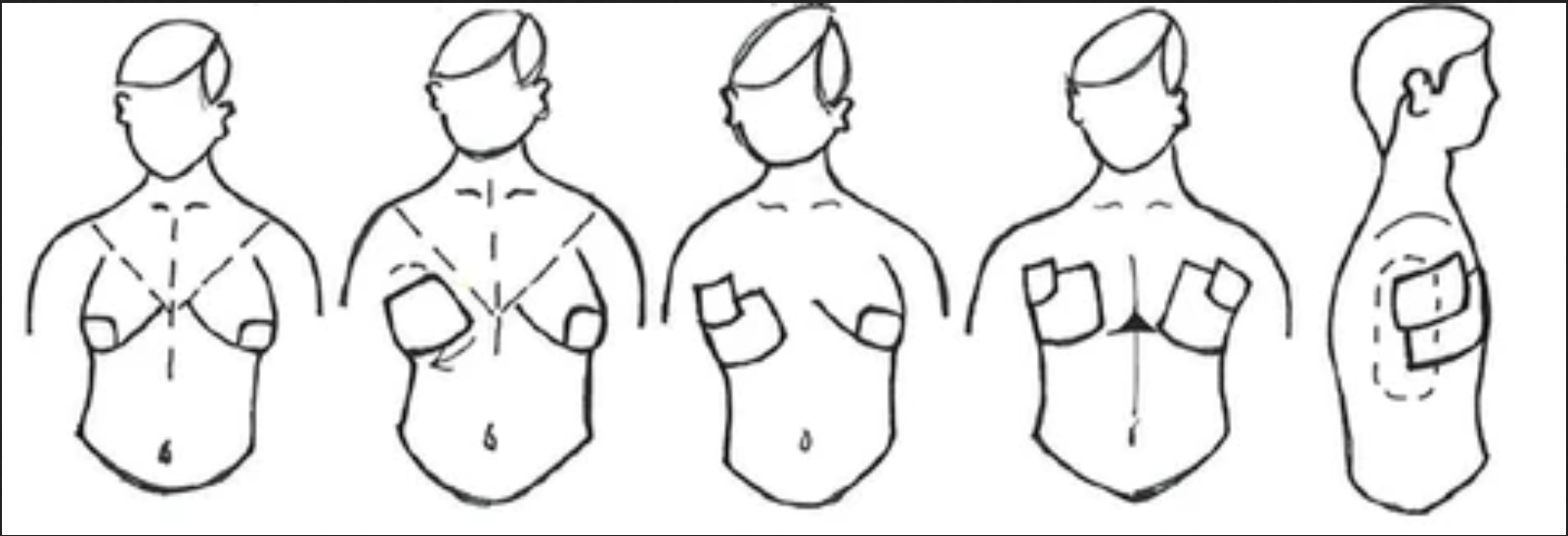

The directional and instructional choreographic quality of line dance could possibly resemble “kettling,” a crowd-control tactic used by police to corral groups of people into a limited space (to be contrasted with dispersal techniques like tear gas or rubber bullets). Once in the kettle, a group of people are surrounded and held in an effort to shift the crowd’s libidinal energy – to de-escalate, demoralize, or simply wear them down. A kettle’s four walls are usually pre-constituted by the built environment, such as grid streets, tunnels and bridges are particularly vulnerable. The repetitive nature of a four-wall line dance similarly congregates people into a limited space. The 90 degree turn ultimately brings the line to face the same original direction – essentially four-walling or kettling groups with line dance choreography. Here, does line dance choreographically disrupt or enable linearity? Do new linearities form or become perpetuated? And is a type of non-space accessed outside of political ontology?

TAKE IT BACK NOW, Y’ALL:

LINEARITY AND POLITICAL (NON)ONOLOGY

Calvin L. Warren’s “Black Mysticism” helps question if line dance may actually enable rather than disrupt linearity, and how this alters political ontology. Warren identifies the problem of ontology in philosophy as a “gap” that can only be understood through African American Criticisms, such as Afro-Pessimism and black optimism. Whereas metaphysics abstractly poses it through the opposition of the ontic and the ontological (or the noumenal and the phenomenal), he proposes that the gap emerges as a binary opposition grounded in an unbridgeable chasm between blackness and blacks. Here, Warren identifies how the acts of repetition and re-inscription perpetuates binary thinking that merely reproduces either side of the caesura. Considering genealogies of line dance in blackness and black performance (action, movement), does the infinite nature of line dance choreography perpetuate this ontological binary gap as oppositions in linearity?

SKYFOX 5 was over downtown Atlanta where protesters and @GeorgiaGuard were dancing the Macarena. Tonight's curfew in the city begins at 8 p.m. pic.twitter.com/W4GM4aEibG

— FOX 5 Atlanta (@FOX5Atlanta) June 5, 2020

In a Fox 5 Atlanta aerial-view video posted on Twitter of troops dancing the Macarena alongside a few protesters, a visible third third line emerges outside of the march or the kettle – a space of dance. In this space, an obvious new linearity forms in a collective line of dance that at the same time divides protesters from troops. The perpetuation of a binary in the creation of this third space maintains a linearity – and therefore a political ontology. Here, we see how repetition in line dance perpetuates a gap in political ontology between blacks, the person line dancing, and blackness, the genealogy of line dancing within the context of a BLM demonstration. When the National Guard Cha Cha Slides with protesters, they engage with blackness while still remaining anti-black. A dancing soldier may point to individual sentiments when engaging in a dance rooted in blackness, however the action does not shift their structural position in the military, and does not institute legal change. In this example, the line dancing troops ultimately serve as an anti-black de-escalation tactic through an appropriation of black dance and blackness. When the Cha Cha Slide Part II finishes at the end of the 11Alive video news report, the protesters ultimately disperse at the time of the citywide curfew.