OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Elude Hard

How can anyone come to understand the pain of others? To be frank, it’s hard. How can one understand the pain of people from another group, e.g., from other generations, other tribes, other countries, other races, other genders? It’s extremely hard, if not impossible. I felt frustrated when I encountered the book UNDOCUMENTS by John-Michael Rivera, a creative writing project focused on the diaspora experience of Latinx people in American history and contemporary experience. I felt I was failing to understand Rivera’s pain and the pain of Latinx Americans collectively and historically, but yet I wanted to understand.

An art prompt is something I know has the potential to function as a bridge, path, or tunnel for connecting human experiences, especially the unique, profound, and personal ones. A prompt is a set of written instructions that anyone can follow to either create works of art or to embody and experience the practice. Prompts are often designed for beginning art students in performance art but are also for everyone to use to experience unspeakable emotions, reactions, and complex stories. Below, I am going to provide you with three prompts I created by looking at two works of diaspora artists and the work of a diaspora writer and abstracting them in the English language. Even though they are designed for bridging my frustration about reading but not being able to “feel” the diaspora experience of US immigrant history, these prompts are meant to introduce you to a method that can apply to any experience of others that anyone wants to understand.

The prompts are meant for you to interpret by yourself and to make the action happen. Whatever you end up doing, it doesn’t have to be the same actions the artists did. The action itself is the core of the practice, that is, for you to tie the experience and remember simply with your body, whatever it is.

Prompt One

- Find a household tool you use to clean your place.

- Find out where the tool was made.

- Imagine the people who made the tool.

- Use the tool to clean the place as you usually do while thinking about the people who made the tool.

Prompt One is referencing Teresa Margolles’s 2009 work Cleaning of the exhibition floors. The work was performed in the 2009 Venice Biennale by the relatives of victims who died in the drug wars in Mexico. The cleaners used mops with a mixture of water and blood from the people who were murdered to constantly mop the floor of the gallery. Artist Teresa Margolles, who is also mentioned in Rivera’s book, inspired Rivera “to see what is in the shadows,” in his words. One aspect of seeing in the shadows could mean seeing the people who died attempting to cross the border. Due to the strictness of ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) agents under Trump’s administration, numerous people died because they put themselves in goods that were being imported into the US from Mexico as commodities. The circumstances were extremely dangerous, which often caused accidental deaths. Rivera indicates that in the ICE system, lots of death is confirmed arbitrarily, by only including blurry pictures, and without confirming the names of the dead person in the official record.

Cleaning of the exhibition floors by Teresa Margolles, 2009. Photo Credit: Galerie Peter Kilchmann.

Prompt Two

- Find a measuring tool. It doesn’t have to be a ruler in any sense. For example, it could be a container.

- Measure your body thoroughly.

- When measuring, don’t just measure size (length, width). Think about comparing your skin tone with your measuring tool, compare the textures of your body parts and the measuring tool, compare the weight of your body and the measuring tool.

- Write down all the data you get from your measurements. Try to use quantitative data.

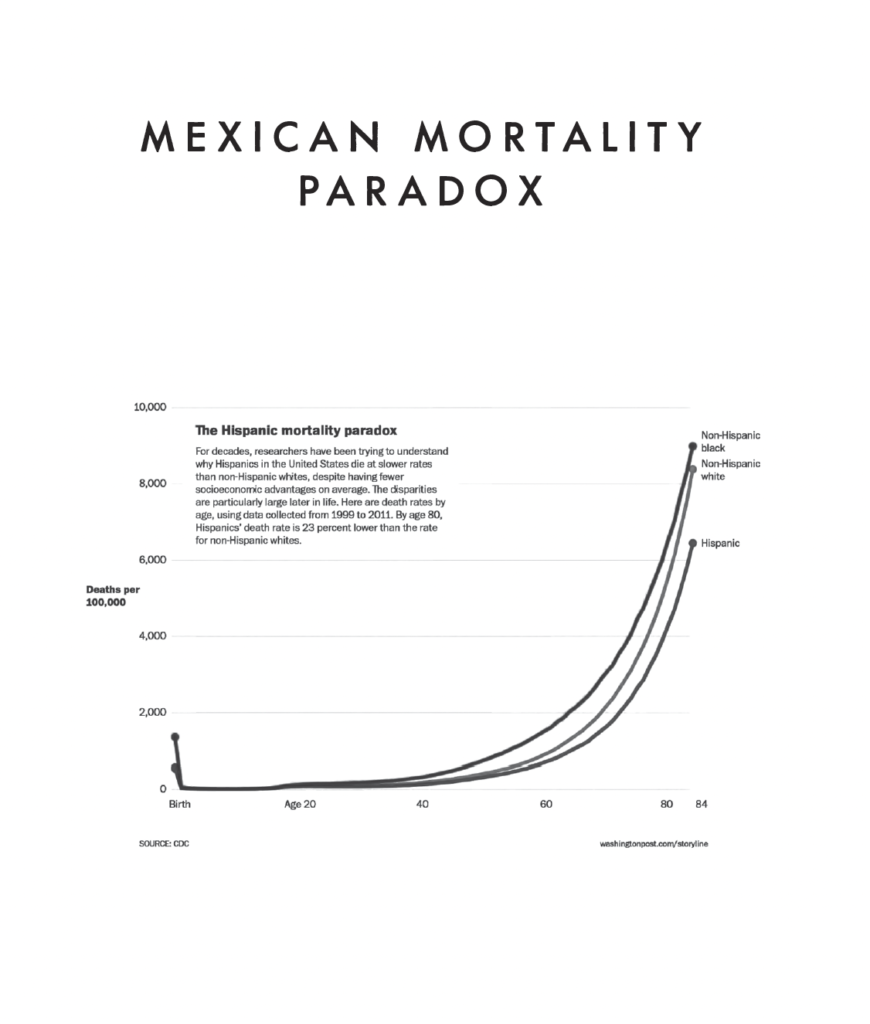

Prompt Two is referencing Rivera’s writing in UNDOCUMENTS Book VII. Suffering from premature ventricular contractions, Rivera lives under the shadow of a possible heart attack. He is always aware of his heartbeat and monitors it by entering ER if he feels an irregularity. Rather than being under his own control, he is tied tightly to the hospital, and the medicine he must take every day—they are authorized institutions, with authorized doctors. His mother, likewise, is suffering from taking aromatase inhibitors to control breast cancer which have the side effect of causing her depression. Being healthy or not is not a mere personal choice. Ironically, when researchers found out that Hispanic people have a longer life than non-Hispanic whites in the US, they couldn’t stand to not investigate this. Given the fact that Hispanic people have severe socioeconomic disadvantages as compared to Non-Hispanic Whites, it became a serious mystery worth the government investing in an in-depth investigation. Theoretically, it should be good fortune for Rivera to know that he would have a longer life, yet all the pills, and hospital visits only remind him of his upcoming death someday in the future.

UNDOCUMENTS by John-Micheal Rivera.

Prompt Three

- Find a surface, which could be a piece of paper, a canvas, or a wall etc. Make the surface at least 3 times bigger than your body size.

- Find a bucket filled with liquid. It can be any kind of liquid: water, pigments, inks, or others.

- Play some music you feel resonates the most.

- Put the liquid on your body and interact with the surface.

- After the music ends, see what you left on the surface.

Prompt Three came from artist Carlos Villa’s 1980 performance Ritual. (The work can be view here) Carlos Villa, a Filipino-American artist who started his early career making minimalist western paintings later concentrated on expressing his multicultural experiences through his art. Ritual is one of his earliest attempts at a big pivot in his art’s direction. Over the course of his career, Villa became one of the most influential Filipino American artists. Carlos’ piece is echoing back an experience Rivera describes in the section AMEXICA in book V. Rivera took a DNA test eventually after long wondering, haunted by the question, “who am I?” The DNA test showed that genetically he is mostly from “Southwestern Europe” and “North America & Andes.” Rivera read through the meaningless, unreasonable DNA sequence. Instead of gaining the greater self-understanding that he was expecting, he became more skeptical of the DNA test, and how he is defined by the test result. The blood test, being another scientific approach to justify, to recognize, to document, to prove Rivera’s body and soul, only left him with an absence of the answer to the question, who am I?

Script notes for Ritual by Carlos Villa. High Performance, Fall, 1989.

Ritual by Carlos Villa, 1980. Photo Credit: Carlos Villa.

Humans naturally have the ability to truly care about what others are suffering and we trust others to have that capability. Therefore, we share our own pain even though sometimes it’s embarrassing, and it often feels like we are going through all of it again when we share. Embodying others’ pain through art prompts has been a path for me to get a little closer to being able to connect, to feel others’ pain. The methodology is really nothing special—it’s about understanding through one’s very own body, something everyone has that gives us pains and emotion, instead of understanding by thinking alone. It is not trying to underestimate any kind of pain by suggesting that it could be shrunk down into small activities that one can do for few minutes. Rather, the embodiment exercise is letting the body carry the weight of thoughts and digest them together with our mind. After all, we might find pain being similar in a way that can bring people together. Touching the pain of others is a way to heal the pain of the self, and vice versa.

When Rivera decided to give a talk about UNDOCUMENTS, he titled the lecture “Eluding All Documentation.” The title almost seems ironic to me—shouldn’t a lecture about the Latinx diaspora experience take an approach of calling for attention to the absence of diaspora records in history? Shouldn’t the title be something asking for being documented instead of escaping documentation? “Elude” is an active verb meaning “escape” as if he is trying hard not to be recorded.

If you have not yet read the book, the contradiction between the two titles might be fully confusing. It might help if you have these questions in mind while you read: under what circumstances would one want to elude “documentation”? What kind of documentation is it? Who is making documentation? If the subjects are Latinx people in the US, who historically have had limited political power, how can they act actively, if not provocative, under the overwhelming power of the state? Can the act of eluding itself be active if it is already loaded with a sense of reluctance? Historically, who has the right to act actively? Who has acted passively? What does it mean to actively “refuse to be documented?” Rivera’s answer starts from his decision to “refuse to look at the already documented” by the US state power. Instead, his resistance is to turn to the undocumented and tell their stories and his own. This is one way to interpret the title of the lecture. But the other way might be more straightforward: because the documents are simply too painful.

UNDOCUMENTS includes stories of missing documents, from undocumented lynchings, to undocumented illegal immigrants, to undocumented detainees, and to the undocumented mother tongue, etc. One shouldn’t ignore how difficult it was for Rivera to write about these stories since they are very personal. Rivera has been recognized by the US bureaucracy as “Caucasian” despite his Mexican parents. Rivera bears the strong guilt of having legal privilege as a result of being treated as a “White American” by the government. Meanwhile, he is suffering from the rupture of being away from his Hispanic culture, the Hispanic community, and from the unfair, racist treatment of being judged by his skin tone. I think Rivera’s writing is provocative. Speaking for himself and the powerless Latinx people, he makes his shame and fears recognizable by the dominating white supremacist and Americentric society. His honesty and grief, and his sorrowful voice act against the gaze of the state despite its inevitable pessimistic and heavy nature.

In UNDOCUMENTS, Rivera creates a unique, innovative, multi-genre approach of mixing poetry, historical archival materials, contemporary art practices, interviews, and personal experience to open a door for the reader to engage a missing, undermined, erasure history of the people of Greater Mexico. The book utilizes the concept of necropolitics developed by Achille Mbembe to analyze and investigate how certain people are made to live and die under the power of authorities’ social and political power. Concretely, in this case, under the colonial power of the state power of the US government, how are Latinx people and their experiences being made invisible? How are their bodies, their existences, and their deaths overlooked, making them “the living dead,” as described by Rivera? The book can also be seen as Rivera’s journey of attempting to document these undocumented bodies and their stories.

UNDOCUMENTS by John-Micheal Rivera, 2021.

“How to document the undocumented?” is the central question of Rivera’s book. When I first started to read, I thought I was getting a practical methodology of a proper procedure to fill in the missing pieces of un-archived history. However, when I closed the last page of the book, I realized Rivera presented a set of incomplete methods. But having this incomplete approach doesn’t indicate his failure. Instead, he has taught me that any archival materials, documents, and data we currently possess, are too little to record the complex and precious human bodies, history, experiences, and both personal and collective memories. Therefore, we should always seek for what is missing, and for the potential violent erasure that exists under the surface of limited documents.

As a reader not belonging to a Latinx background, it has been difficult (maybe even inappropriate) to summarize and simply give you a few ideas of the sad racist history and stories Rivera presented beautifully. However, the practice of using prompts often reminds me of the ways in which my experiences could be like someone else’s. During the process, many memories came up from things I felt before and stories I heard before, and the stories I learned from readings came together through my body. What I am trying to do here is not to re-tell the stories Rivera presented in my second language. Diaspora, under the current circumstances of globalization, leads to a desperate search for the languages of connecting, healing the massive trauma created by a large-scale political circumstance. It has become clear that the issues of immigrants, refugees, eco-systems, human health etc. need to be addressed outside of the framework of nationality. An art prompt exercise might seem small and personal, but it is also a reminder of something fundamental—that humans suffer pain one way or the other. It could be the very first step toward making the experience we want to approach but lack of know-how relates to our body directly.

John-Michael Rivera, author of UNDOCUMENTS (2021) and an associate professor of English at the University of Colorado Boulder, was invited as a guest speaker for the Aesthetics and Politics Lecture Series, co-hosted by the West Hollywood Public Library and the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). The lecture, titled “Eluding All Documentation,” was presented on November 19th on the CalArts campus. The recording of the lecture can be viewed here.

The article is written by Sang Chi Liu, a current M.A candidate of the Aesthetics and Politics program at CalArts. They are also a practicing performance artist born in Taiwan.

Reference

Rivera, John-Michael. “UNDOCUMENTS,” The University of Arizona Press, 2021.

Roth, Moira. “The Art of Multicultural Weaving,” High Performance, Fall, 1989.