OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Description and Philosophy: Filling Ecofeminist Gaps

On April 16, 2025, ecofeminist scholar and activist Greta Gaard visited the California Institute of the Arts as part of the lecture series Ecofeminisms: Practices of Survivance. At the REDCAT Theater in Los Angeles, Gaard gave a talk titled Milking Mother Nature II: Ecofeminism, Milk and Oil, in which she developed an argument about the similarities and interrelationships between the exploitation produced by the oil and dairy industries. Focusing on the case of California, the presentation offered a clear description of the social and environmental criticality of these two activities, explaining in detail the scale of both phenomena and their consequences. In addition, Greta Gaard developed a theoretical framework in which the intersection of these two industries appears in three fundamental aspects. On the one hand, the land where oil is extracted is geographically contiguous to the land where cattle mega-farms are located. On the other hand, most of these facilities are located in racially and economically disadvantaged areas, affecting the quality of life of marginalized groups. Finally, metaphorically, oil extraction and intensive dairy production belong to the same imaginative sphere, linked to the idea of “milking” nature beyond a threshold of sustainability.

In the following pages, I will try to develop a personal response to this encounter with Gaard and her ideas. By situating the talk within the broader reflections presented by the author in “Critical Ecofeminism,”1 I will highlight the descriptive value of these investigations, but also reveal some conceptual flaws that undermine the overall practicality of the project. In particular, I will focus on the causal explanation that Gaard offers to explain how the current precarious situation has arisen and argue that the proposed relationship between Western culture and capitalist exploitation requires nuance and clarification. From this perspective, the purpose of my contribution is not to refute the ecofeminist paradigm, but to reflect on how it might be improved. Just as Gaard situates her research in a self-critical framework, developing a “critical ecofeminism” that “challenges the field’s foundational assumptions”2 even beyond Richard Watt’s “moment of interrogation,”3 this essay seeks to improve the explanatory possibilities of this analytical paradigm.

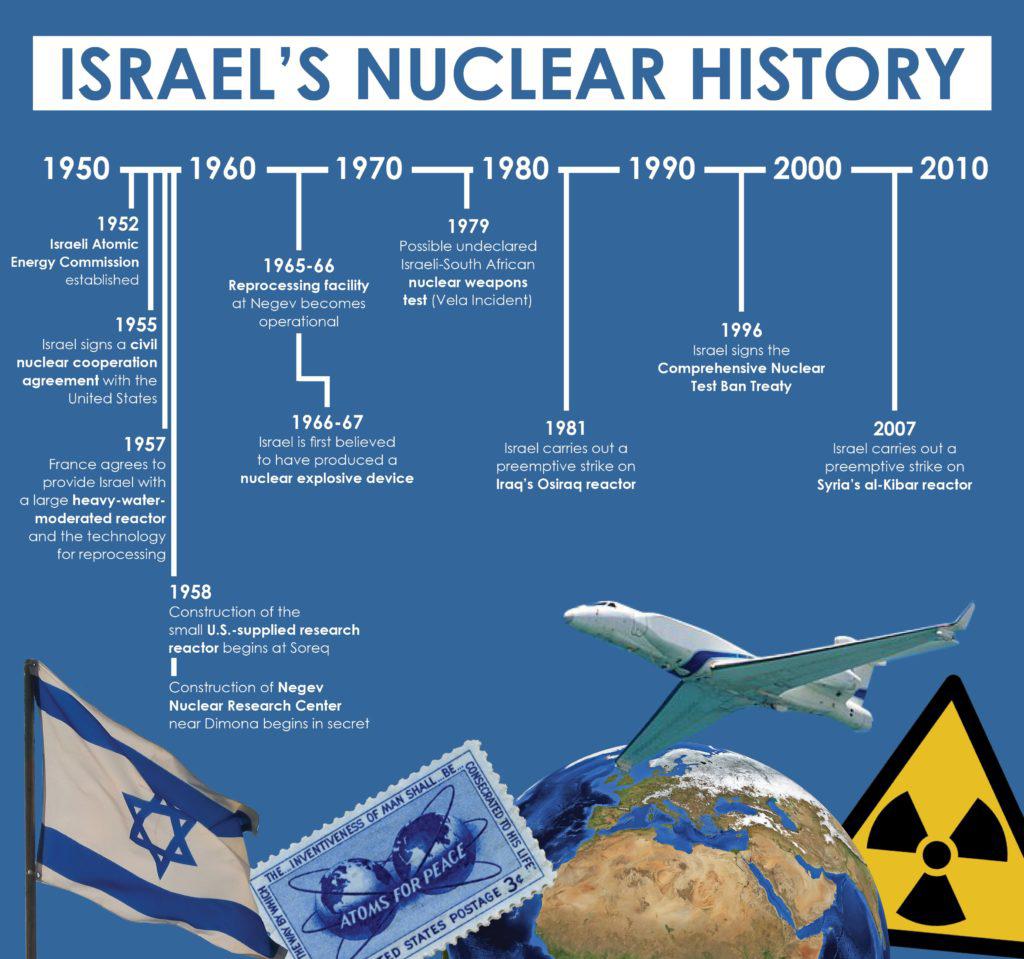

In her lecture at CalArts, Gaard does not overtly mention the conceptual aspect of her work. Instead, the descriptions, images, statistics, and graphs of the cases she examines implicitly make the nature of the problem clear. Put simply, ecofeminism is a movement and critical framework that emerged in the 1970s and considers it crucial to address the issues of ecology, sexism, racism, and social inequality as interrelated manifestations and consequences of the capitalist exploitative system. For this reason, the position has always been intertwined with numerous critical and philosophical traditions. Starting from a Marxist matrix of economic and social critique, ecofeminism develops where scholars in the fields of ecology, sociology, political science, and economics recognize the limits of their own standpoints and seek to move beyond them. In Gaard’s presentation, however, it is not the big names or complex concepts that reveal the importance and urgency of the situation. It is the scholar’s ability to make the audience aware of the paradox of certain dramatically real situations that makes the problematic nature of these realities intuitively clear. The contrast between the cattle ranches and the multiple oil wells just behind the animals leaves no room for interpretation, and violently reveals the nature of the problem. Even without considering the possibility of vegan and vegetarian diets, the idea that the meat and the milk consumed by millions of Americans every day are produced less than a few miles from where oil is extracted should be enough to concern even the most ardent advocates of a carnivorous diet.

Figure 1

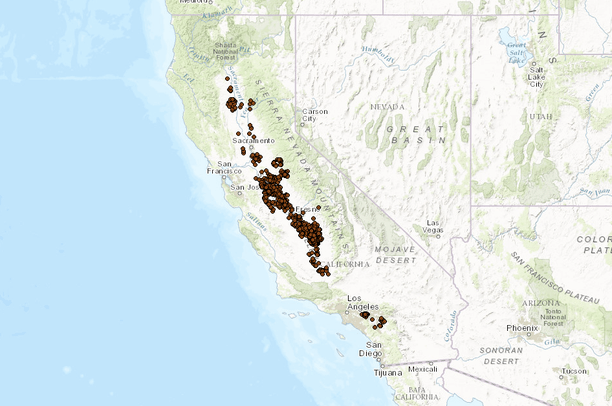

Map of California oil and gas fields

Figure 2

Map of cattle magafarms’ distribution in California

Figure 3

One of the many cattle megafarms in the US

Gaard’s presentation then goes beyond this initial intuitive evidence, carefully highlighting the many consequences that stem from the relationship between milk and oil. After showing how often these two realities intertwine in California’s Central Valley, the scholar explains and demonstrates how the areas affected by these industries are mainly those inhabited by lower-middle-class people, who are often employed as workers in the factories. In addition, the presentation reveals the actual criticality of the situation, ruling out the possibility that we are facing only a strange but healthy visual combination of oil and cows. Using statistics and data on air quality, for example, Gaard shows how oil extraction combined with the gases released by the animals’ dried manure makes the air around those areas uniquely toxic. Finally, the lecture shows how this problem affects all social classes, even if it mainly has an impact on marginalized people. Using the example of the health damage caused by an oil well near a high school in Beverly Hills, Gaard clarified that no one can consider themselves immune to the risks of this type of industry.

Thus, in just one and a half hours, Gaard was able to explain to a non-expert audience the relevance of both a technical and a theoretical statistical study of ecofeminist issues. In this sense, the presentation was of fundamental value in denouncing the critical nature of a reality that is often ignored or not fully understood. After the talk at REDCAT, I don’t think anyone present could still believe that this constant intersection between the oil and food industries is a negligible and insignificant reality.

With this indelible awareness, in the continuation of this essay, we will try to understand more precisely the extent of the explanatory power of the ecofeminist paradigm, highlighting the limitations that arise from its holistic view of reality. In particular, we will show how the desire to develop an all-encompassing understanding of exploitation and subordination in the contemporary world conflicts with the need to analyze the specific details of each reality. Indeed, we will show how ecofeminism, in order to develop a suggestive image that reveals the interconnectedness of different forms of precariousness, must sacrifice a multilayered understanding of the causes of each phenomenon. In the following sections, believing it crucial to intervene actively on all the causes of a phenomenon to change its course, I will first show how Gaard never develops a rigorous and satisfactory historical, genealogical, and causal understanding of the present. Then, I will reiterate how this absence is a consequence of the very structure of ecofeminism. Finally, the conclusion will invite the reader to consider the possibility of an ecofeminism in which the current balance between an all-encompassing view and attention to detail is revised in favor of the latter.

First, to avoid misunderstandings, it is important to clarify the usefulness of investigating and exploring these issues. The purpose of the following pages is not to justify the existence, validity, and usefulness of the ecofeminist perspective. The evidence provided by the seriousness of the current situation and the points of contact between the ecological, social, and economic crises are sufficient reasons for developing a holistic perspective on these problems. Consequently, the request for clarification regarding an ecofeminist genealogy of the current situation stems from the possibility of strengthening the foundations of ecofeminism itself.

While the holistic view of ecofeminism manages to overcome some of the limitations of previous positions, such as their inability to provide a clear and vivid picture of the critical nature of the present, this progress comes at a price. As noted above, Gaard’s presentation at REDCAT omitted any causal explanation of the contemporary world. My argument is that this ultimately prevents the audience from developing effective tools for action. However, the absence of this kind of reflection is not in itself evidence of a limitation of the ecofeminist perspective. In fact, in the written work of the ecofeminist activists, one can still find suitable genealogies. In particular, Gaard herself addresses this issue in “Critical Ecofeminism,” where she states that the intertwining of animal and oil exploitation stems from a certain Western way of being. In accordance with Val Plumwood’s theories, Western rationalism and dualistic thinking, on the one hand, would create the conditions for the contemporary multifaceted exploitation. On the other hand, these same cultural traits would also prevent any redemptive action, eliminating the possibility of listening to the suffering of Earth’s ecosystem.4

Therefore, as a second step, it is important to understand whether the existence of an ecofeminist explanation of the present complements the descriptive perspective presented in the lecture. That is, we need to understand whether the ecofeminist perspective can further develop the descriptive capacities shown by Gaard in her lecture, making it possible to produce a transformative action. Unfortunately, I find that the causal understanding of the present proposed by ecofeminism does not fill in enough gaps. In turn, an analysis of the position she takes allows us to understand how the very nature of the ecofeminist perspective prematurely dismisses action that could build a better future.

As mentioned above, the ecofeminist perspective is formidable in describing the contradictions and problems of contemporary reality. However, the insistence with which, in her historical and causal explanation, this precariousness is solely linked to certain theoretical developments in Western culture not only diminishes the complexity of this culture but also undermines the effectiveness of the Ecofeminist paradigm from within. By omitting this conceptual component from her presentation, Gaard has managed to reveal all the descriptive power of her position. Yet, I would argue that Gaard’s causal analysis of contemporary exploitation groups’ diverging experiences of exploitation in a way that preempts practical solutions. The cause can be found in her structural inability to highlight the specific causes of the problems. There are three compelling reasons why the causal explanation Gaard offers does not work. That is to say, there are three reasons why Gaard’s causal explanation doesn’t allow an understanding of the phenomena so that one may try to change their course successfully.

Engaging with the three arguments in order of complexity and importance, the first flaw concerns the nature of the relationship between Western people and intellectuals. Speaking of the inability of Westerners to perceive stimuli from nature, the scholar says: “Euro-Western culture is so permeated by Cartesian rationalism that children are taught from an early age not to receive—and certainly not to trust—the information being sent continuously by the animate world that surrounds us.”5 Furthermore, regarding the division between body and mind, she states that “from Plato and Descartes, Westerners have learned to treat consciousness rather than embodiment as the basis of human identity.”6 In this way, Gaard traces the conceptual matrix underlying today’s exploitation back to certain theories that originated in the West, believing them capable of shaping and directing a people’s self. While developing a clear cause-and-effect relationship, this explanation has a flaw: it understands historical development as directed by certain ideas, rejecting the possibility that philosophical thought is itself a product of a particular culture rather than its creator. For example, it was not Plato who instilled in the Western mind the separation of soul and body, of becoming and being. On the contrary, it was the complexity of the concrete situation in Athens at the beginning of the 4th century B.C. that produced Plato’s reflection on the state, knowledge, and being. It was Athens’ defeat in the Peloponnesian War, combined with the immorality of the government of the Thirty Tyrants, the decline of classical theater, and the progressive revision of traditional rituals and religion, that led Plato to think in a certain way and to develop specific solutions to real problems. It is the reality of a particular culture that carries the potentiality of certain ideas, not someone’s thought that creates an entirely new cultural paradigm. Thus, to return to ecofeminism, the first step in understanding the current situation must be a reevaluation of the extent to which philosophers have the power to shape historical progress.

Secondly, ecofeminism arbitrarily chooses which Western concepts to address and which are the only valid interpretations of them. Let’s consider the Western dualism between culture and nature. For critical ecofeminism, this dualism is precisely “the key to the ecological failures of Western culture.”7 Or even: “Western culture and pivots on the human/nature, mind/matter dualisms are not only is gendered, raced, and classed, but also constructs a colonialist identity that Plumwood calls the Master Model.”8 As in the first case, the presence of this division in contemporary exploitation is undeniable. However, the causal link with certain intellectual currents does injustice to these positions and prevents the development of a real understanding of the phenomenon.

In the words of Val Plumwood, Gaard explains how the dualism of Western culture derives once again from “Plato and Descartes, who treat consciousness rather than embodiment as the basis of human identity,”9 advocating for the need of situating human identity “in material and ecological terms.”10 There are two problems with this position. First, it assumes that the division between soul and body in the two philosophers produces a difference in the value of the two elements. But in Descartes’ “Meditations on First Philosophy,” the primacy of the soul is never understood as a rejection of the body. The division between mind and body occurs always and only in a gnoseological sense. If we want to know what’s real, we have to start from the certainty of consciousness. But this does not mean that the body has less value. Similarly, Plato believes that the soul and the body have different functions and different qualities, but not that one is inherently better than the other. As the myth of Er teaches,11 it is only because of the unavoidable and fundamental relationship of the soul with the body that the former reaches the most complete level of knowledge in the afterlife. That is, soul and body, like every component of reality, exist only in a fundamental relationship to each other.

Moreover, moving away from the examples suggested by Gaard, to define Western culture as characterized by mind/body dualism in terms of the value of each component is itself a mistake. If we look at the Christian—specifically Catholic—matrix of Europe, this is particularly clear. Of course, Catholic doctrine teaches that each human being is a union of a soul and a body. However, this dualism, and that between human beings and other animals, never has a moral connotation or indicates the superiority of one side. Without going into biblical exegesis, the first composition in the Italian vernacular—Umbrian— by St. Francis of Assisi in the 13th century explains this point well, affirming the equality of all God’s creatures: “Laudato sie, mi’ Signore, cum tucte le tue creature.”12 And again, St. Francis refers to the sun, the moon, Mother Earth, and other natural elements as “Frate” and “Sora,”13 showing how they are as valuable as humans. On the other hand, regarding the separation of the soul from the body, the equal importance of the latter is well explained by the doctrine of the resurrection of the body after the Last Judgment. Theologically, the Apostles’ Creed states: “Credo [….] in carnis resurrectionem,”14 explaining how human beings cannot be considered complete without their flesh. Therefore, although contemporary exploitation remains a dramatic reality, the ecofeminist causal explanation that links it to the dualism underlying the dominant European culture must be revised in order to understand the real causes of the problem. Indeed, for the reasons just stated, it would be unfair to claim that Western culture emphasizes only the role of the soul and the immaterial, disregarding any function of the body and materiality of beings.

Figure 4

Bealieu-sur-Dordogne, Romanesque Tympanum, XII a.D.

Under the Apostles, a detail of four dead corpses coming back to life

Having said that, we can now turn to the third and most fundamental point regarding Gaard’s causal explanation’s shortcomings: her all too generic use of the concepts of nature/culture and the paradoxical consequences of such an argument. In summary, Gaard believes that contemporary discriminations, injustices, and exploitative practices stem from the “Master Model” born within Western culture. That is, Gaard asserts that by distancing themselves from nature, Westerners have developed a culture—an artificial value paradigm—capable of justifying actions that violate natural harmony and sustainability.15 The paradox of this position lies in the possibility of explaining the artificial exploitation of nature through the concept of culture, while at the same time holding the human/nature dualism to be false. How can a natural being, like any other, construct something that transcends nature itself and undermines its balance?

To believe that culture is the cause of the precariousness of certain contemporary realities, one cannot eliminate the dualism between nature and culture, but only invert its polarity. While culture has historically been considered superior to nature, the ecofeminist perspective values natural harmony over human intervention. Indeed, if humans are part of nature like any other creature, then their actions cannot be outside the realm of what natural laws allow. Thus, either humans are somehow separate from nature and their actions exceed the harmony granted by natural laws, or the exploitation humans produce is still part of natural harmony. In clear contrast to the main goal of ecofeminism—to solve current problematic situations while reintegrating human beings into the cycle of natural harmony—both of these positions would require solutions outside of what ecofeminism can offer.

In conclusion, the causal understanding developed by Gaard proves incapable of accurately grasping the reasons behind current problems, making it difficult to outline a plan of action. While Gaard’s paradigm is formidable in creating a clear picture of the criticality of contemporary reality, her all-encompassing standpoint preempts many practical responses. Since she has to find a common cause for profoundly different phenomena, such as the exploitation of nature and its creatures, racism, and gender discrimination, Gaard must resort to very broad concepts that fit any context—“the West,” “nature,” “culture,” “body,” “mind,” and so on. The broader the concept, however, the greater the indifference of those who use it to the particularities of each situation. The three points discussed earlier clearly show the extent of the problem: the ecofeminist perspective has stretched concepts and obscured the differences between individual phenomena to such an extent that a causal explanation without internal paradoxes is now unthinkable.

At the same time, the emphasis placed on the value of ecofeminist descriptions and the evidence of the interconnection between certain contemporary phenomena show that spontaneous forms of activism are not the solution either. In other words, ecofeminism should not impulsively move from theory to action in an attempt to resolve its own contradictions. As various NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) movements demonstrate, immediate and direct opposition does not lead to lasting solutions. Protests such as the Italian ones against TAV (high-speed train between Turin and Lyon) and TAP (Trans Adriatic Pipeline) in Val di Susa and Puglia, respectively, are examples of this form of ecological activism that spontaneously arises from local populations opposing new infrastructure that alters their landscape. Despite their international fame, these movements are too focused on a specific issue and risk being perceived as the whim of selfish people who would prevent important progress just to defend their own interests. While it is true that the broad critical framework of ecofeminism struggles to grasp certain realities, an overly internal and personal perspective risks losing the objectivity necessary for long-term action. Focusing solely on the urgency of their situation, these movements fail to grasp the connections between their condition and broader trends. In this way, trying to immediately block a process without understanding its reasons, these movements become blunt opposition.

Figure 5

NO TAV signs during a NO TAV manifestation

In these few pages, I’ve tried to suggest that the future success of ecofeminism depends on its supporters’ ability to understand current phenomena in all their specific and general complexities. That is, I hope to have shown that the success of ecofeminism hinges on balancing and finding a middle ground between all the forces that produce a given reality. To achieve this balance, ecofeminism must offer more than a general view of reality. Second, this change in perspective has to lead to a more profound revision of the ecofeminist model. Specifically, I believe that, to achieve a complete understanding of contemporary phenomena, ecofeminism must abandon the presumption of being on the right side of history and engage in pragmatic dialogue with its adversaries. Only by abandoning the ethical connotations of the ecofeminist struggle can we adequately understand our world and create the possibility for profound change. Only by understanding the social demands that certain precarious situations—such as farms located near oil wells—seek to address can we begin to envision alternative, more sustainable ways to meet those needs. Only by recognising the social need to extract oil and raise animals regardless of the capitalist system will it be possible to develop ecofeminist interventions through stricter regulation of these practices. From this perspective, I believe that, taken as a whole, the European Union’s regulations and directives on emission standards, animal rights, gender, racial, and religious equality, and workers’ conditions represent the best example of how to address the issues identified by ecofeminist activists.

Endnotes

- Greta Gaard, Critical Ecofeminism (Lexington Books: Lanham, 2017) ↩︎

- ibid., X ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid., XX “Who is listening?” Gaard asks, highlighting the inability of contemporary Western people to recognize the living soul of the nature around us ↩︎

- ibid., XIX ↩︎

- ibid., 41 ↩︎

- ibid., XXV ↩︎

- ibid., XXIV ↩︎

- ibid., XXV ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Plato, Republic, 614A-621D ↩︎

- Saint Francis of Assisi, Canticle of the Sun, 1224 “Be praised, my Lord, with all your creatures” ↩︎

- “Brother” and “Sister” ↩︎

- “I believe in the resurrection of the body” ↩︎

- Gaard, Critical Ecofeminism, XXIV ↩︎

Works Cited

Descartes. Meditationes de Prima Philosophia. Edited by Donald A. Cress. Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, 1993

Gaard, Greta. Critical Ecofeminism. Lexington Books: Lanham, 2017

Plato. Republic. Edited by Paul Shorey. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1942