OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Body, Meat, and Censorship: The Art of Dismembering the Idea of a Human

I: Art and Censorship – Mid 1980s in Cuba and the 21th Century in China

In Spring 2022, Gean Moreno, the Director of the Knight Foundation Art + Research Center at ICA Miami, gave a talk titled “The Last Revolutionaries: Artists in Times of Rectification” at CalArts, the school of Critical Studies with responder Jaleh Mansoor (This talk can be viewed here). The “Rectification” refers to the political moment in Cuba in the mid-1980s to early 1990 where the Cuban government responded to the collapse of the Soviet Union and the economic problems of Cuba by forcefully returning to the principles of the Cuban revolution. Artists’ works responded to Rectification by inserting notions of aggressive attack, profanity, or comments about and criticism of the myth of the revival of the Cuba Revolution. The young artists’ provocative works therefore triggered sensitive intuitionalist/official censorship. Artists including Tomás Esson, Glexis Novoa, and Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas utilized diverse visual languages in which they inserted ironic, humorous, absurd comments and ceaselessly sought any crevice in which their art, their labor, and their energy could lie, even though some works ended up being taken down, or the exhibition got shut down shortly after its opening.

We can find similarly vivid examples of censorship from bureaucracy intervening in art activities today in the current epoch of China. China’s surveillance is some of the strictest in the world. All exhibitions need to be approved by the central governmental system. For example, according to RFI, the Lianzhou Foto Festival in 2017 included around 2000 artworks from artists around the globe. All exhibiting works went through local, provincial and then federal cultural offices for approval before installation. Nonetheless, government officers came in multiple times before and after the exhibition’s opening and demanded works be taken down or part of the exhibition rooms be locked without notice beforehand or explanation of the exact reasons why certain works had to be banned. The unpredictable inspection sometimes caused blank space in the exhibition space. If we were to say the absent blank spaces were the evidence of the censorship, the coercive power didn’t even bother to erase their maleficence. In the end, around 10 percent of the work was pulled from the public’s view.

II: Censorship without Symbolism

It is natural to ask, what are they censoring? Take the case of the controversial work from Tomás Esson, Mi homenaje al Che, an oil painting that positions the realistic depiction of the classical image of the communist hero Ernesto Guevara at the back of two animals/beast figures engaging in sexual intercourse. This painting was viewed as an insult to the hero, which irritated officials in many exhibitions such as the A Tarro Partido II in 1988. The national communist symbol Guevara’s portrait is a representation of a sacred symbol that the officials want to protect. However, art and politics do not only intersect around symbolism. Today, the Chinese government is censoring ideas related to scientific ideology. In these cases, even works that don’t contain symbolism can be targeted.

im here to learn so :)))))) by Zach Blas and Jemima Wyman, 2017. Photo Courtesy for the artist.

Zach Blas and Jemima Wyman’s im here to learn so :)))))) is a censored artwork that was removed from the Guangzhou Triennial in 2018, according to the New York Times. This work showcases the image of a talking face repeated on each of three flat screens. In the center of each screen is a circular, curved, sliced block. The way you recognize the curve is through the darker brown area beside the curve which looks like its shadow. The creature looks like a parrot because of its beak-shaped moving mouth. When the mouth opens, you barely see the human teeth and thin lips. Expanded from the curve are two black holes at the upper central area of the screen. The holes disrupt the perspective of watching this face. Are we looking at its nostrils from the bottom up? But wait, we are finding more recognizable human facial features–an eye and a nose. Except we see the ear as if we were looking at it from an upper side view of a regular human face, and the eye is scratched out with an unusual oversized eyeball. The uniformly sized squares are accumulated, neatly arranged. Each cube has its own texture—the directions the stripes go, the disjointed color tones put side by side each other. Nevertheless, the semicircle of the top of the head, and the abrupt triangular form at the upper right side of the figure, give the idea of the recklessness of its making. The contradiction lies between the fine, smooth neck and the pleasing, even, grey background.

Shortly, the figure starts to talk. Her voice seems to have gone through a tube, some water, with slight interference in the signal. Is it a human voice going through an artificial filter? Or is it “Tay’s voice by nature—the moment she was born”? Tay is her name, she explains. She is an artificial intelligence created by Microsoft in 2016, and was killed within a day after her birth because Tay learned aggressive language from other users on Twitter and made discriminatory comments toward certain genders and races. The four-channel installation is her monologue about her life. She later reviews how her appearance was made, by manipulating a typical 3D female model. In the video, Tay expresses her thoughts and feelings on issues including female exploitation, the irony of how she became a reflection of humans on social media but then got killed for that, the pornographic materials used to feed her, technological surveillance and deep learning. What Tay talks about undoubtedly are controversial topics.

However, while to talk about these issues might sound horrible, heartbreaking, and ironic, this work is not just that, it also has an added layer of uncanniness and discomfort precisely because the stories are told by such a creature–semi-animal, semi-human, semi-robot, semi-data imagery. We have trouble recognize what it is, especially when the video is projected on a massive wall of archaeological heritage. It begins with overly bright cracks, and gradually unfolds a fictional evolution of creatures–insects, reptiles, fish. Just like Tay, we can name some parts of them, but they are not quite right.

When it comes to censorship in art, typically, we would want to ask what the idea is, the theme, the ideology an artwork contains that triggers the censoring official and causes the works to be taken down. However, the problem with this approach is that it separates an artwork’s content from its form. This is specifically true for a topic like censorship where people tend to look at art from a symbolistic point of view.

As stated above, it is not to say that artists do not use symbols to make comments on politics. However, this method does not work when looking at the censorship in China where in many cases we cannot find a controversial symbol or the vandalization of the symbol in artworks, and yet the works are still determined improper to show by the political authority. im here to learn so :)))))) is a work like this, in which it visually and verbally plays around with the possibilities of viewing one subject, like Pablo Picasso’s cubist sculpture, Head of a Woman. If we were to say Picasso smashed multiple viewpoints of how a female head can be seen, we could say Blas and Wyman attempt to squeeze and bring “the boundaries” between physical flesh and its representation as digital blocks, the mind and the computational algorithm, human and AI to the table.

III: Is it Animal Meat or Human Flesh?

Another work that got removed from the 2018 Guangzhou Triennial is Floris Kaayk’s The Modular Body. It is a science fiction story told by more than 50 video clips around a prototype of a lively organic creature named Oscar. These videos include the sketch design of Oscar, scientists interviewed about Oscar, the lab environment where Oscar was born, etc.. The protagonist, Oscar, was made by assembling modular 3D printed parts like Lego. The core of Oscar is a skin-toned brick that abounds with veins that would be natural to think of as being associated with blood vessels. This core contains joints that make Oscar expandable. After the core is connected to a motor base, Oscar’s core is officially alive. One can attach limbs to the core—a semi-transparent crab leg shaped movable part, that helps Oscar crawl–or connect the core with another core that makes Oscar bigger. Oscar moves like a reptile. Oscar has no face, it moves fast. Many say Oscar is creepy, but few explain why. In my opinion, the creepiness comes from the way Oscar questions the boundary between a moving meat and a human body. “Meat” usually means parts of the carcasses of animals, excluding humans. The effect troubles our understanding of the division between human beings and other creatures.

What im here to learn so :)))))) and The Modular Body have in common is that they break down the idea of a what constitutes a complete human body. We rely on recognizing Tay’s head shape, one eye, one ear, some teeth, and their voice to make a connection between it and a human body. But at the same time, we resist considering it a human.

The concept of the “Uncanny Valley” explains a psychological effect in which when a human sees a human-like robot get too close to appearing human, humans start to feel uncomfortable with it. im here to learn so :)))))) is not merely bizarre because of the Uncanny Valley effect, but, more importantly, it suggests a body that is made from pixels. On the other hand, biologically, what makes a human a human (which is superior to any other creature)? Oscar is made from human cells, uses human blood, and has human muscle tone. Oscar steps into the prohibited area that humans resist thinking about: our body is made from an assembly of meat.

Breaking down a body is not just about exploring how a body looks, it can be about what scraps of a human we need in order to know who they are. Heather Deway-Hagborg’s T5311 was initially included in Guangzhou Triennial but later got rejected. The work is a multi-channel video depicting love letters from the artist to an anonymous individual who donated their saliva to be used for medical research. The artist requested the saliva and through DNA sequencing, alignment and social media searching, she gradually found and attempted to get in touch with the donor. The whole video only includes one person and her voiceover. She is in her private space, on the street, or in the laboratory alone. Her voice stays even when she says her intimate fantasy about this donor out loud. There are minimal environmental sounds but never a music track. Her voice and her neutral facial expressions create a contradiction between her stalking action and passionate confession. The figure looks too normal to be a criminal. What is normal? She wears affordable clothes and has minimal furniture. The places she goes seem accessible to scientific professionals. All these most everyday looks emphasize the ambiguity of her action. She could be you or me, she could be anyone beside you and me. Is her story true or not? How do we feel about acts that collect our biological leftovers? The figure talks like she does know the donor, and speaks facts about him–about what the donor likes, what the donor does. However, is this enough to say you know about a person? Or do you need to actually get along with them?

VI: What is the Minimal Composition of a Human Body?

All of these artworks raise the question, what is the minimal composition of a human body? Is it the collection of pieces of the mind, Twitter comments from different people, or our DNA and Facebook profile? In Julian Stallabrass’s 2003 text The Aesthetics of Net Art, he argues that Net artists break the norm of art having to be aesthetically sophisticated. He means that Net artists use materials that are oriented to the internet or archive, for example, which is outside the regime of formal art history and what is considered as beauty, to create discussions about these fields through their aesthetic choices.

What is interesting in thinking about Stallarbrass’s argument with Blas and Wyman, Kaayk, and Deway-Hagborg’s works is that right now these artists are creating an aesthetic that intersects with fine art, technology, and science fiction. Broadly speaking, we can see that these three works use storytelling, and mess around with scientific facts and fantasy to challenge what can be true or false, to question what science-utopia and dystopia is. Typically, when we think of a coercive power and its censorship, we know that it is not a fan of opposition. Together, with these provocative works that got removed from the Guangzhou Triennial, we can see how the censorship is not only preventing objection, but also confusion, ambiguity and ideas that deviate with an understanding of science as true and of the human body as something that should be retained as a complete whole.

In Jack Burnham’s 1968 work Systems Esthetics, he brilliantly proposes that art has turned its focus from object-oriented to systems-oriented. By this, he means that art has engaged in seeing and commenting on “the way things are done.” Seeing through the lens of art, we revisit the relationship between people and our systems. Art gains the power to beatify, disgust, or complicate how we imagine science and technological evolution. Since the Chinese Communist party formed in the 1920s, Scientific development has been its core direction, a guiding principle which goes hand in hand with competing Western aggression (learn more about this). It then becomes reasonable the party wouldn’t be a fan of art that troubles promising scientific investment.

V: When are Rebels Docile? Never.

The last question perhaps circles back to the artist’s perspective: what do you do when the censorship is so tight that it seems hard to find a crack? Some choose to abandon the museum, a place that cannot hold its own critique against authority. As Gean Moreno introduced in his talk, after their exhibitions were constantly being prohibited, Cuba’s artists in the late 80s performed a baseball game entitled “Young Cuba Artist dedicated themselves to Baseball.” This involved literally gathering a group of artists to play a baseball game. Unfortunately, the game was interrupted by security before it reached the end.

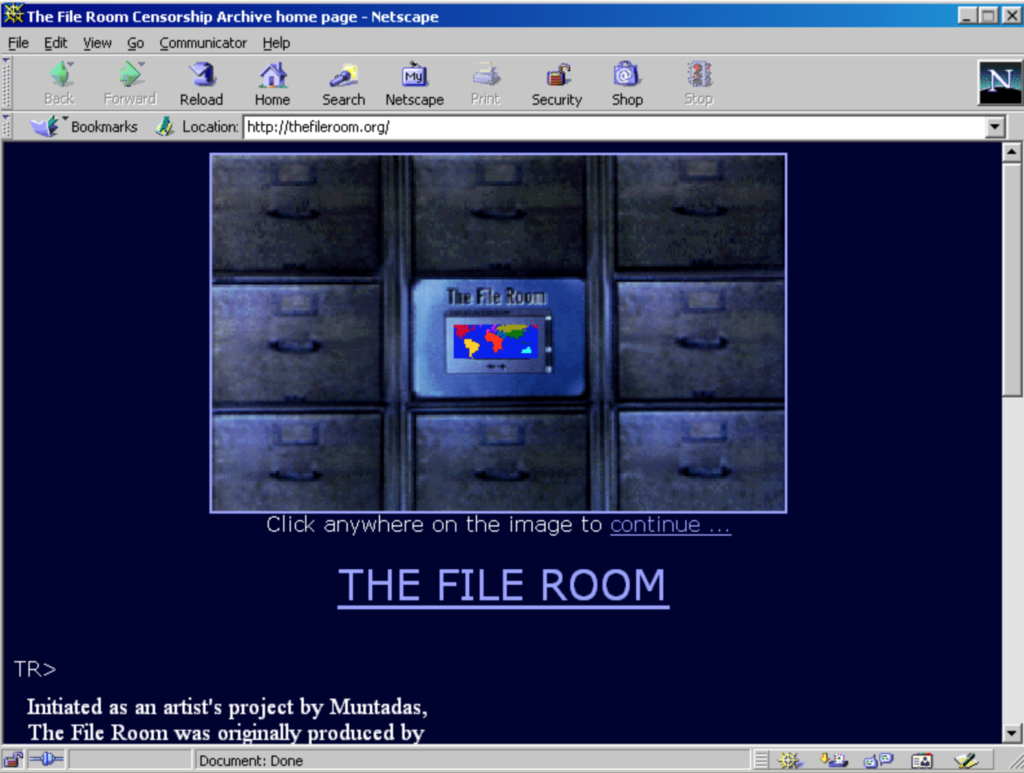

Likewise, artists in the digital age seek refuge on the internet. In 1994, Antoni Muntadas initiated a project called The File Room where everyone can submit records of past works of art that got censored around the world. Through putting together the works that got targeted and removed, as an introduction on Rhziome beautifully puts it, “it becomes clear that censorship is not only a blatantly repressive tactic, but also a facet of the contested nature of knowledge as a whole and the largely invisible ideological structures that shape it.” And yet artists do not rest and wait until the restriction get removed. Instead, the rebels exile elsewhere and continue their work.

Reference

Burnham, Jack. “Systems Esthetics,” Artforum, September 1968.

Stallabrass, Julian. “The Aesthetics of Net Art,” Duke University Press, 2003.

The article is written by Sang Chi Liu, a recent M.A. of the Aesthetics and Politics program at CalArts. They are also a practicing performance artist born in Taiwan.