OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Beyond the Flicker

Dr. Bridget Crone was a visiting faculty at the Aesthetics and Politics program at CalArts during the fall of 2017. She is a curator and a writer working at the intersection of political philosophy, media theory, contemporary performance, and moving image practices. Her work explores questions of livenes and the image. As visiting faculty of our school, she was invited to open that academic year’s WHAP series. Her talk on October 6 was titled “Flicker Time: Liquid bodies and cosmic states”.

This talk seems to be expanding some of the work she did for her essay “Flicker-time and fabulation: from flickering images to crazy wipes.” Moreover, this essay and part of her talk concentrate on the film The Flicker by Tony Conrad. In her essay, she explains:

“This essay explores the flicker or flicker-image as a flash of light that has the potential to disrupt the mechanics of vision. The most elemental of images, the flicker is at the very basis of both vision and mechanical image production; it is the flash of light that makes an image possible, and it is the continuous flickering of light across the eye (or lens) that connects visual perception with time perception through the operation of critical flicker frequency: the speed at which the brain joins those flashes of light together and thus perceives the movement of time.”

In the talk, she expands her argument beyond the mechanics of vision in order to consider the political implications of the flicker effect in The Flicker and other materials from films, but also literature. She argues that this elemental image, the flicker, is able to disrupt those mechanics as well as the perception of time as linear. By doing this, she works through the flicker as a way of experiential time travel.

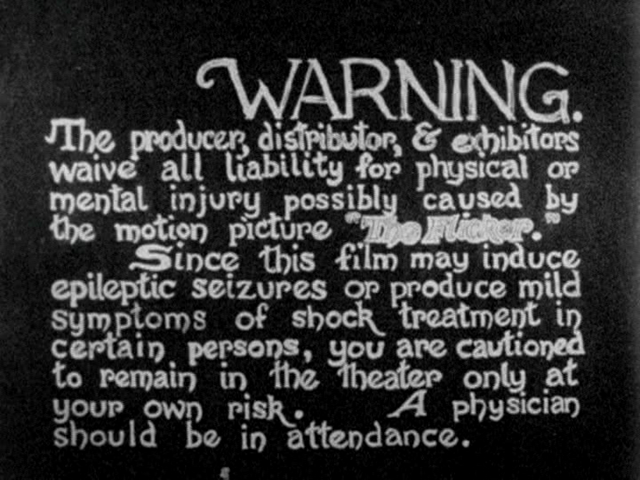

Tony Conrad’s The Flicker (1966) is a pioneer of a particular type of structural film, flicker films, as characterized by P. Adams Sitney in his book Visionary Film The American Avant-Garde (1943-1978). What they share is the flicker effect, a stroboscopic effect dedicated to the eye. In her text, Crone explains that this effect involves is a specific frequency of flickering at work, the critical flicker frequency. To put it simply, there is a spectrum of durations and intervals that create the flicker effect. If the duration augments and the frequency drops, this effect will not create the usual shock to the eye that the flicker film intends, it will be more a quick alternation than a flicker. All the same, there are no specific rules to flicker films – the flicker deals with the mechanics behind affecting the eye. Films like The Flicker intend to create a strong, slightly dangerous effect. The first shot of The Flicker is a Warning and disclaimer regarding the people that might have an epileptic response to what they are about to see. The flicker effect presents itself here as something slightly dangerous that is also an experience. The message of this plaque seems to be that only a real sensory experience can create such effects.

The experiences of flicker films differ substantially. In his Arnulf Rainer (1960), Peter Kubelka takes this to the field of image and sound, going a little further into disrupting continuity. Later examples incorporate color and referential images, such as Paul Sharits’ T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (1968). Through the years, there have been even digital explorations of the flicker effect, but the material characteristics of digital work are completely different. The basis of the flicker film is to use alternations that create a discontinuity through moving image, which is perceived as continuous. Crone argues that Conrad’s flicker film allows us to have a sort of immersive experience that would allow us to think and even inhabit the spaces between the images. The intensity of the sensory experience helps the spectator to lose itself between the images.

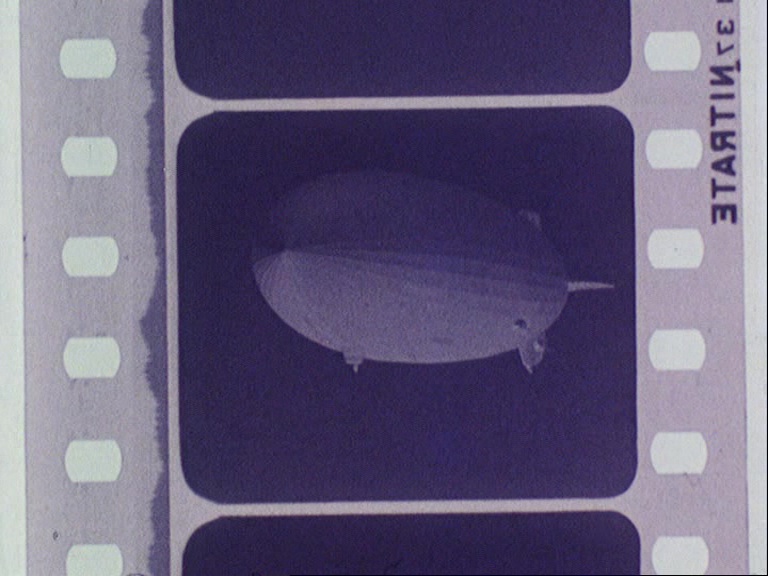

But, is there a space between the images? In analog cinema there is a small space between the images. The images that we perceive as continuous when we go to see a film print (an experience that is less common in everyday life, but still very common at CalArts) are in fact discontinuous. What we are seeing are still images projected at a standard speed of 24 frames per second. But as seen above in this still from Morgan Fisher’s Standard Gauge (1984), depicting a small piece of nitrate film, there is a small gap between these images that is necessary for the physical illusion of continuity. That space, as the discontinuity itself, is not perceivable. Indeed, what Conrad, Sharits, and many others are doing is re-claiming the discontinuity of the time-based experience of cinema, against the illusion of continuity. Thus, adding to Crone’s argument of time-related consciousness-raising through discontinuity. Between each still of white that creates the luminous parts of the flicker film, there is a small space. The flicker itself, if it lasts more than a frame, is perceived as a small continuity that is in fact discontinuous.

After drawing the aesthetic implications of the flicker effect, Crone discusses the political implications of this disruptive experience of time and light: The Flicker proposes a new way of seeing and being in the world, thinking outside the norm by abolishing the continuity and transparency that usually comes with narrative cinema. It does this by providing a more embodied experience of watching, both mental and physical (and in this, she summons Deleuze’s famous expressions in his cinema books: give me a body/give me a brain). The flicker film as such creates the experience of inhabiting a different time (thus, time travel), and at the same time, produces a hyper-consciousness of time (both what and how time is). This different experience of time, disruptive and non-linear, she calls “flicker time.” The value that this work holds, for Crone, is how the disruptive embodied experience expands our awareness It is a transformative living experience. Moreover, this experience creates a space of non-productivity, as the person concentrates in the alternations of black and white to the point of extreme immersion.

The beginning of Joyce Wieland’s Reason Over Passion (1969) can be thought of as a flicker film. It alternates between images of Canada (including the Canadian flag) and black. The sensation it creates is not only of discontinuity but also of a technical difficulty. The spectator cannot ignore that this film is not magically appearing in a screen, but that it is actually being projected. That is contrary to the usual effect of the “open window to the world” created by continuity and transparency in narrative cinema. The flicker becomes slower and less frequent, and as we see more shots of the Canadian flag, the images keep fading to black, as if it was always trying to start over (turning on, losing strength and disappearing back to zero). Once the images of the landscape acquire continuity, words will appear on top of them. First in French (La Raison Avant la Passion) and then in English (Reason Over Passion), the two official languajes of Canada. Suddenly, the letters that form the words start to change places, creating new combinations that mostly make no sense as words.The flicker will occur between the words, and the original combination will start to lose meaning and feeling to the point that it is no longer possible to know if it was the reason over the passion or the passion over the reason. By doing this, the film not only creates a confusing experience to the eye, that is always trying to make sense out of the words in the screen, but it also creates the idea of a confusion of the mind, between reason and passion.

Like the films Crone mentions, Reason Over Passion is an experiment on drawing attention to the discrepancies between movement and time. Crone brings up that Deleuze, in his cinema books, argues that experimental cinema acts upon or works through the split between the body and the mind. The idea of the “experimental” is not only bound to experimentation but also to experience. The experience of the making but also the experience of watching. All experimental films concentrate primordially on the bodily experience that the spectators have in relation to the work. Crone concentrates in the potential affects that can come from this apparatus, which relates to the body-mind split and the way it can be rejoined. But a question arises from this: while the spectator is having the embodied experience, who is producing it? Whose labor is making this possible for the others?

Morgan Fisher is a filmmaker whose work circles around the film apparatus and the way cinema works in different levels, from the mechanics of vision to the politics of viewing. He is also strangely connected to Crone’s talk in a more direct way, as he edited one of the other films she analyzed in her talk, the cult horror film Messiah of Evil. In his film Picture and Sound Rushes (1973), he describes a film as something in which “there are two basic components, picture and sound. Each of this components can be present or absent,” which relates directly to Tony Conrad’s work, in which there is a sense of the white parts being the presence of the image and the black parts being the absence of it – as white implies the presence of light and black, its absence. Fisher, as Conrad, is looking at film in its most elemental materials. Both their works are dedicated to understanding what is that combination of image and sound and how is it that they work.

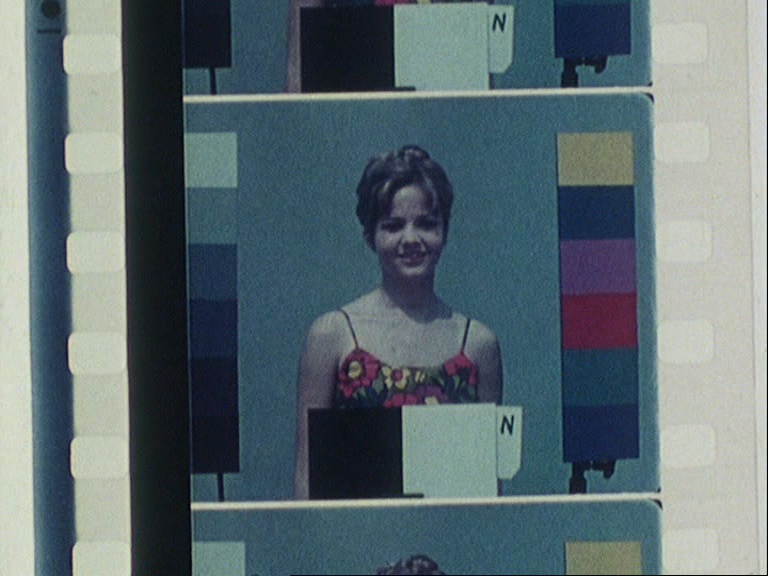

In Standard Gauge, Fisher starts by explaining the technological development of the camera and the projector, from Edison’s individual machine, the kinetoscope (in which one person could look at moving images through a peephole), to the collective experience of the Lumière brothers, who had a machine that could both capture image and project onto a surface for people to see. The film shows selections of 35mm films that can be seen complete, perforations included. They are treated as fragments of celluloid and nitrate instead of being projected at their regular speed. They are viewed as in an operations table. He talks about the 35mm format and the way it is the standard format everywhere, and the culture around this standard – even the fragility of some of the materials of which the standard gauge was made, like the highly flammable nitrate film. He does not create a perceptual effect of discontinuity like Conrad and his flicker, but still he addresses directly the work behind the illusion of continuity that is necessary for a film to exist as such. Both go against that illusion of continuity: one through the senses, and one through a combination of this and an analysis of the differential labors and techniques necessary to make a film, from the crew to the “china girls,” those images of Caucasian women surrounded by colors and tone schemes that are used to calibrate color and luminosity while processing a film. The standard skin tone, the one the density of the material is prepared to react better to, is white.

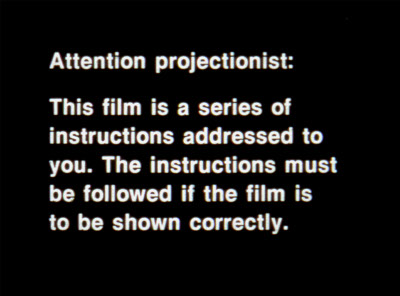

A few weeks ago, there was a projection of some of Fisher’s work downtown at REDCAT as part of his exhibition titled, of course, Passing Time. Included in the program was his film Projection Instructions (1976). Luckily for me, the projectionist was a friend of mine, so I heard about some of what she had to do for the screening/performance. As its name suggests, Projection Instructions includes a series of instructions for the projectionist, which are written in white words in a black background. Similar to Conrad’s film, it starts with a notice. This time, not for the spectator but for the projectionist. The disruption of the experience of the spectator here is complete, as they are not the focus, the projectionist is. It forcibly transforms the film theater laborer into a performer, who has to perform some sort of cinematic score made out of actions from their daily work, such as “Throw out of focus” or “Turn off the lamp.”

Half of a decentering of the spectator and the filmmaker from the cinema experience seems to be taking place. The focus shifts to the projectionist, and so does the importance of the actions. The theater worker becomes a performer. This denaturalizes the experience that usually takes place inside the theater, makes visible a labor that is usually invisible. At the same time, the projectionist has little chance to refuse the orders that come from the film. Projectionists are one of the people that make the experience of watching this film possible while being the only ones that can have a fully embodied experience of it. For accomplishing this performance, my friend, who knew the film, had to practice two or three times before the public screening.

I think the work of Morgan Fisher among others helps to answer some of the questions Crone poses in her essays and public talk, as well as it creates new ones. This question regards continuity and disruption in the cinematographic experience, both towards the mechanics of vision and the politics of this mechanics. At the same time, they create a space for experiencing time and denaturalize this experience. By way of a conclusion, itself perhaps flickering: someone once said about Fisher’s Phi Phenomenon, which shows a shot of a clock without the second hand, that while watching it, he realized that a big part of what we pay for watching is not more than minutes passing.