OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Back to Future: Cuban Rectification Art and Chinese Avant-Garde in the 80s

Introduction——

On March 17th, curator and visual artist Gean Moreno joined the Aesthetics and Politics Lecture Series of Spring 2022 at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, California. His talk, with respondent Dr. Jaleh Mansoor, an associate professor of Art History at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, took us to review a unique part of Cuban art history of the mid-80s, a period defined by “Rectification.” Specifically, he examined how the artists indexed the paradoxical nature of society and culture in transition by returning to the American identity and ancient myths. My following essay will depart from this talk and engage with the artists and artworks from a comparative perspective between China and Cuba.

Historically, Cuba and China have long been in a complicated yet close relationship since both of their revolutions (China in 1949 and Cuba in 1959). In fact, Cuba was the first country in the Americas to recognize the legitimacy of the PRC, and it remained China’s second-largest trade partner on this continent for decades. To draw a comparison, I will introduce the Chinese concept of the “literati” in parallel with Moreno’s “essay” to reveal the commonalities and differences between these two models and countries when it comes to aesthetics and politics. Hopefully, this comparative view will provide us with a synthetic framework to examine the dynamics of contemporary art in post-Socialist countries.

I. The Talk and the Script

At the March 17th talk at California Institute of the Arts, curator and artist Gean Moreno led us to explore a rarely studied aspect of Latin American art history, the art and artists of the mid-80s’ Cuba. My following discussion will be developed from the original content of his talk on March 17th and the written script he based his analysis on to show another perspective of the issue. There are two major parts to Moreno’s talk: the talk itself and the written script. I will attempt to investigate and summarize both aspects from my modest understanding of the two materials.

The script, which Moreno wrote in advance before the talk, is an article on the Cuban artist Juan Francisco Elso and his work, “Essay on America.” The writing is a comprehensive engagement with the tradition of the Americanist essay and how Elso’s work fits in and breaks away from it. The central argument lies in “contradiction” which is evinced through the essay tradition, Elso’s work itself and its interpretations, and the sociopolitical characteristics of Cuba in the mid-80s. Divided into six, the script itself, which Moreno might have used as the written reference for his talk, also partially follows the essay structure which targets and unravels a specific topic in each section with a directed argument. It reminds one of Common Sense by Thomas Paine—short, critical, and specific. His command of language was also clinical and individualistic which draws from his original reading while maintaining a critical distance from the subject matter. The rhythm in rotating between history and theory also facilitates the understanding of the complexities of Elso’s works, especially regarding art history and social conditions. Moreno shows a sharp sensitivity towards the two aspects in moving from one paragraph to another, which ties the whole essay together.

Differently, his talk was more impromptu and objective, showing the images of more artists besides Elso and elaborating on the social and art-historical background mentioned in the script. Although the oral form would sacrifice some of the literary articulateness, it paints a broader and more accessible picture for the audience to enter a niche field of Latin American visual culture, especially when the ancient myths were involved.

The talk was an ambitious summary of the Cuban artists of the Rectification period. According to Susan Eckstein, The Rectification Process started in the mid-1980s and is a political campaign “launched in 1986” as a campaign to “rectify errors and negative tendencies.” It was also a movement to reiterate a renewed commitment to the Revolution by clamping down on market features.[1] The subjects of Moreno’s discussion primarily emerged from this period and reflected many defining problems and possibilities emergent from this unique cultural and historical strata. In detail, Moreno reveals the heterogeneity and generative potentiality in this group of Cuban artists by showcasing a series of artworks in tension and sporadically, in seeming harmony with the Rectification institutions. Instead of looking at the works from a binary perspective, Moreno contends that the Rectification art marks a significant departure from their precedents in medium, concept, and implications, thus offering us an intriguing example to study in relation to art history and our time.

In the following dialogue with Dr. Mansoor, Mansoor raised questions from an art historical perspective and reasonably related the Cuban artists in discussion to global modernism and European (and Soviet) Avant-Garde. The discussion instantly “turned” contemporary when Dr. Mansoor began to compare some recent works by Latin American and Black artists with Elso’s works, which also shows a similar allusion to the ancestral and historical. Overall, their discussion provides a coherent framework when considering Cuban art and its preceding and ensuing connections within or beyond the Americas. Additionally, it also helps to incorporate Cuban art into a broader discourse by expanding the tradition of American essay and identity to other examples.

Instead of studying a large group of artists, Moreno spotlights in his script one artist, Juan Francisco Elso, and one series of his works, “grouped as ‘Essay on America’ at La Casa de la Cultura de Plaza in Havana.”[2] “Essay,” as an obvious historical and literary connotation, leads Moreno to revisit this tradition of Americanist essay and pinpoint a few crucial characteristics and limitations of this form. Specifically, Moreno departs from the medium itself and shows us a contingent and intriguing connection between “the sculpture” and “the essay” with a survey of “the tradition of the American essay.”[3] Through an informative review of this literary tradition, Moreno demonstrates the essay’s functions of accounting for “heterogeneous populations,” “historical injustices,” and the philosophical implication of being “anachronistic” with an empirical context. With this background, Moreno explains Elso’s strategic and artistic turn to “the essay” by showing the essay’s continued relevance to the mid-1980s’ Cuba as “a moment of transition” as “an anachronistic irritant.”[4]

Por América [José Martí]

Juan Francisco Elso, 1986

The Bronx Museum of the Arts, Bronx, NY

The two different mediums of writing and speaking also inspire one to raise questions about the differences (and their implications) between speaking versus writing, discussion versus lecture, or to ask other medium-specific questions. Apparently, the essay as writing is an effective demonstration of its historical function of conveying and persuasion concerning a specific idea or phenomenon, in Moreno’s case, Elso’s sculptures. When spoken as speech, the essay was not as engaging because it would require more than the texts to persuade the audience, but more performative elements at work to get across the text itself while unavoidably changing the performativity of a written text—it could expand it but also ruin it. After all, the text is destined to be performative as a material instead of as a reference. This contradiction of the essay was also symptomatic of Elso’s works. “Essay on America” was suggesting an issue, or alternatively, another possibility inherent in the medium of the essay, either as writing or speaking. The sculptures, if read as writing in Elso’s visual language, would be an implicit statement that any medium is subject to a plural life as the only solution to reconcile the aforementioned paradox, as implied by the name of Moreno’s script, One is Already Two, and Two are Many.

A Screeshot of Gean Moreno’s Virtual Lecture at CalArts in 2022

Additionally, the structure of Moreno’s script demands our critical attention because of its efforts to coordinate the weight of history in a theoretical discussion while the “essay” discourse is also given due respect. Section I introduces Elso’s work, “Essay on America” and contextualizes Elso’s turn to the essay with several questions regarding its decolonial turn. Section II attempts to answer the previous questions by examining the essay’s “anachronistic” status and its potentiality of revealing the lies in art, and possibly, in society. Section III follows this inquiry into the social sphere and explains the Process of Rectification from a changing perspective, in other words, how things changed in and beyond Cuba during this period. The details of history emphasize the dynamic character of the Revolution thus bringing out the argument that Elso’s sculptures are a refusal to accept the ongoing social configuration and coherence. Section IV departs from the historical background of Elso’s works by reframing “Essay on America” as not merely a reflection of but “a risky proposal” of how the sociopolitical paradox should be understood and structured.[5] With this new direction, Section V synthesizes the previous history and theory by exemplifying one specific work, El pájaro que vuela sobre América in “Essay on America” to explain “the loss of concreteness” in Cuban culture mirroring “the absence of non-alienated production” in the Cuban Revolution. This argument also reiterates the function of the essay being a tool of mediation through different dimensions of society. Section VI is a conducive detour to examine the influence of Tatlin and the American shamans on Elso’s work. By drawing from the two seemingly contradictory sources, Moreno further explores the discursive character of “Essay on America” by alluding to Letatlin and shamanism and concludes the essay with a philosophical summary of the work as the history of absence and the reality in tension. Moreno starts the essay with the Americanist essay and closes it with a heavy note on the Cuban history. Although the history here is not reflected as mechanical reflection, it gives us the space to draw the China-Cuba comparison.

II. The Process of Rectification and Chinese Reform: the “essay” and the “literati”

Based on his script, which almost resembles an Americanist essay itself in terms of its discursive form and analytical tone, we have a clear understanding of how art is shaped by “the Process of Rectification.” It was a political shift “characterized by the eradication of a number of economic practices, independent real estate sales and small scale retail for instance, in order to curtail profit-orientated tendencies that had flowered and regenerated forms of private accumulation,” a further explanation of Eckstein’s introduction. In the following analysis, Moreno clinically defines the character of this process as “a tangle of contradictions.” This contradiction lies in the Revolutions itself and the critical distance between reality and practice in both cultural and socioeconomic spheres, meaning that the Revolution had become removed from its context. A new situation stands out here: the Revolution sought to “renew” itself by going back to its original doctrines while the domestic and international conditions of Cuba had already changed significantly to make this “renewal” as “anachronistic” as Adorno’s “essay.” Conceivably, this sociopolitical paradox was also affecting every aspect of Cuban life including the arts.

In this climate, Moreno introduces the protagonist of his “story,” Juan Francisco Elso, who participated in this period of cultural “renewal,”[6] and reframes his practice as a prescient experiment in expanding the American identity in a plural way, a revealing process of decolonial critique, and a methodological return to the mythical past which was based on his survey on the Americanist essay. Moreover, Moreno breaks away from the essay framework and sees Elso’s sculptures as a provocative proposal to refuse the preexisting referents and stand in odds with the ongoing reality and even with the paradox itself.

With a return to the past, the “root” of the Revolution, Cuba aspired to renew itself in terms of culture and politics. However, with a similar appearance of returning to the mythical Caribbean past, Elso exposes the farcicality and contingency of this “return” by differentiating Elso’s artistic “return” as a point of “dialectical tension” with this absurd reality. This tension was not achieved through Elso’s reflection of his time (although I believe his work would facilitate this reflection) but through building and orchestrating the multiple disparate yet liberating layers of his sculptures.

To imagine a return to the past is also to prospect a march to the future. This imaginary narrative also reminds me of Chinese art in the 80s. By reading Moreno’s script, I am more than tempted sentimentally and academically to adopt a transcultural framework to further explore this narrative caught between the past and future. Additionally, the “anachronistic” and “evanescent” qualities of Elso’s art also mirror some comparable practices in mid-80s Beijing.

Che Guevara visiting China in 1965. To his left (on the right in the photo) is Deng Xiaoping.

There are also, serendipitously and indeed unsurprisingly, several differences and commonalities between China and Cuba in the mid-80s, especially concerning political and cultural shifts. Unlike the Process of Rectification in Cuba, China during this time was boldly yet cautiously opening up its economy under Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, and with the economy, the culture. In 1976, following the Death of Mao Zedong, the long-time revolutionary leader of the Chinese people and a steadfast leftist, Deng, a more practical-minded leader himself, started to turn the helm toward market-oriented development. Accordingly, he opened up state-controlled resources and sectors for privatization and foreign investment, which eventually led to many new social problems and ironically, the later rise of China as a world power and economic giant. Cuba’s “return” to Rectification was also a reaction against the broad picture of Socialist countries turning “Capitalist.” Apparently, China spearheaded this shift starting from the early 1980s.

However, like the generation of Elso, some Chinese artists made an anachronistic return to the past in parallel with the simultaneous growth of interest and investment in Western cultural movements. A potential comparison and dialogue can be established between this group of Chinese artists and Juan Francisco Elso’s generation because of the similar politics and history of China and Cuba during the latter half of the 20th century, both previous members of COMECON countries, a Soviet-led political and military alliance among the Socialist countries. Although this alliance was diluted and eventually disintegrated following the Fall of Berlin Wall, its influence continued in multiple post-Socialist societies like China and Cuba.

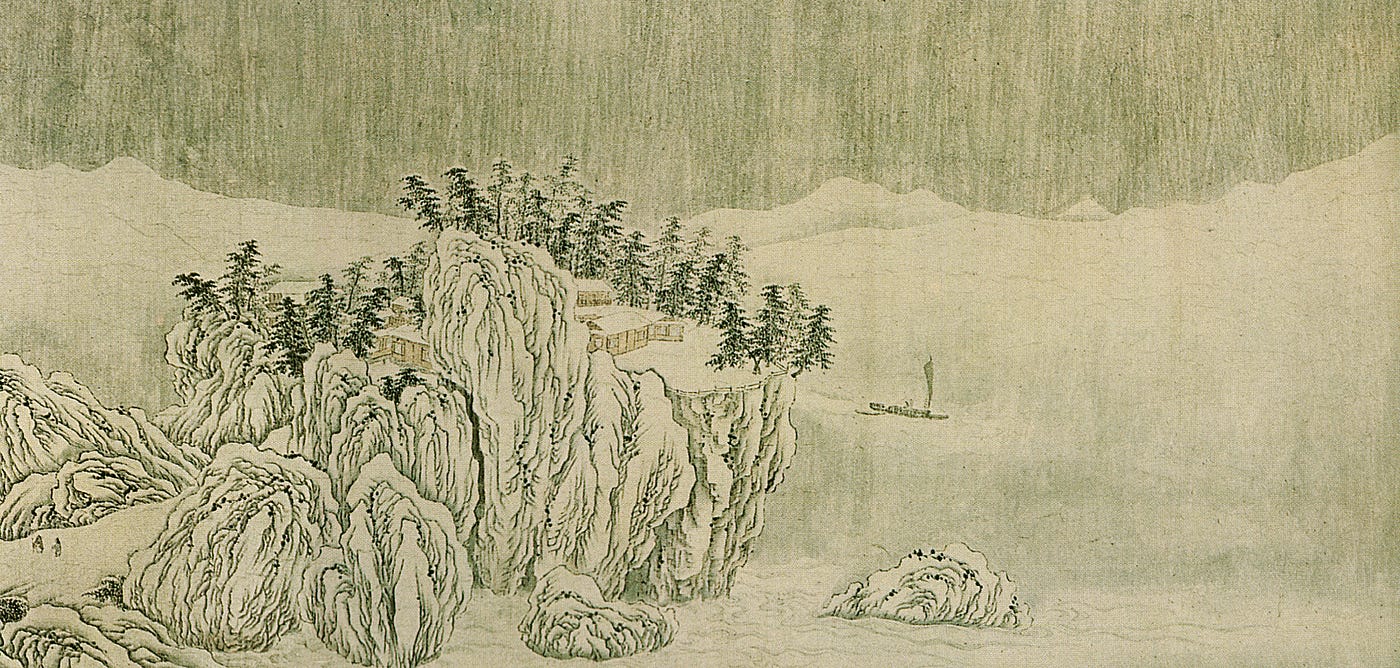

Instead of returning to a tradition of mysticism and Americanist essay, Chinese artists returned to their literati tradition of art-making and writing. It was a vital force influencing Chinese history since around 200 BD. This influence was defined by the unique role of the literati class consisting of a group of people identified and shaped by a relatively consistent collection of characteristics—the dual character of the bureaucrat and intellectual, a privileged position in leading political and cultural shifts, and most importantly, the major producer and protector of Chinese literati art including ink wash painting, calligraphy, poetry, and music. Because of the literati identity, many artists in Chinese history also acquired and remained in a unique position in formulating and communicating their works. The literati artists were historically allowed and encouraged to carry critical weight in the works, in parallel with religious connotations and esoteric renderings. Like the American essayists, literati artists always created the works that would remind one of Elso’s “Essay on America.” In fact, in the literati tradition, there was a principle of not dividing between the essay and the painting or between the poetry and the painting, which was highly regarded as a hybrid quality of having “the poetry in the picture, and the picture in the poetry.” This tradition also echoes the issue with different mediums in the previous paragraphs.

The Picture of Snow Along the Yangtze River, Wei Wang (literati painter and poet), Tang Dynasty (618-907), China

However, instead of “Essay on America,” it would be “Wen (also meaning essay and text) on China.” In fact, the literati are also called “Wen Ren” meaning “the people of text/essay.” Especially in the last days of the absolute Chinese monarchy, some Qing-dynasty literati poets and writers started to ask questions about what China is, how it stands against other nations, and how the Chinese stand against other cultures and ethnicities—head-on the question of nationalism and modernization. Like the tradition of the essay in Cuba, and from Liang Qichao to Lu Xun, every writer provides a slightly different answer on what it meant to be Chinese.

A Photo of Dashuifa (now in ruins) at Yuanmingyuan Garden, Beijing, China

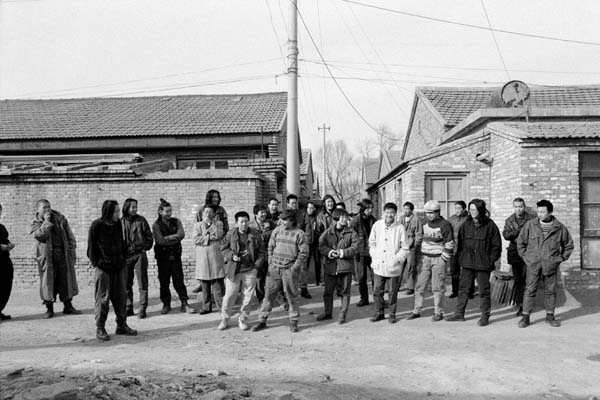

During the mid-1980s, an artist village entitled Yuanmingyuan Artist Village was established on the ideals of literati artists. Yuan Ming Yuan, the first three characters in this community’s name, denotes the location where the artists resided but also where the renowned imperial garden, Yuanmingyuan Garden, was built and written about by Manchurian emperors, designed and reformed by European missionaries and designers, represented favorably by numerous Chinese artists and officials, destroyed by colonial armies and political unrests, and secretly visited and portrayed by the Chinese intellectual artists prosecuted and constricted by the Cultural Revolution. Eventually, this garden, a “multi-temporal, multi-semantic, multi-perspectival” installation of “vastly different historical strata and cultural contexts,” and certainly a space of nostalgia for modern and contemporary intellectuals, became the home of a group of Chinese artists during the mid-1980s. It was striking to see that with a modern and capitalist turn in Chinese society, some artists in the village turned to the literati tradition of creating critical texts and images. Similar to the Cuban artists in the Process of Rectification, the Chinese artists, without contradiction, also showed a disposition drawn from conceptual art and embracement of installation formats and materials reproduced during the rapid modernization of the Chinese society. Like how they would adopt the form of “return” to instead “renew” and regenerate the Revolution in Cuba, the Yuanmingyuan artists also sought to renew China through recycling the past. This past could include the memory of the Yuanmingyuan Garden, the physical and mental remnants of an imperial garden or any motifs or forms repressed but now allowed in the literati tradition. This prospect is evident in the Manifesto of the Free Artists of Yuanming Yuan Artist Village:[7] “The sun has been rising from the horizon before the dawn, shining upon the path of our spiritual pursuit. A new form of existence has been confirmed on the ancient and broken garden on the Chinese land!” It was a remarkable and touching statement. It was also anachronistic because of the tension between its form and context. Yuanmingyun, a heterogeneous installation itself, was only a symbolic return to the past in order to generate a future too idealistic to be realized. The artist village was also built upon this dialectical tension between a “revived” literati tradition and a rapidly modernizing society. Geremie Barme described this phenomenon as “the Romance of Ruins”[8], and this “romance” could also be understood as a continuum of the revolutionary fervor before 1976.

III. Conclusion and Afterthought

This “anachronistic” romance can be understood in parallel with Adorno’s “essay” and Elso’s return to American shamanism. Essentially, they were not to be interpreted at face value as the homages to the past, because the pasts were inevitably altered and fragmented at the first place. This romantic return to a more “revolutionary,” or more “original” phase of society is meant to be performative and critical when undertaken by individual artists because the narrative would have already collapsed within itself even before the process repeated as farcical and unnecessary. However, this fragmentation of Chinese history, like how Moreno expected of the Cuban audience, was not inherent, but acquired through the penetrating yet discursive gazes of the public, which were equally immersed in a contradictory reality. Yuanmingyuan Artist Village was not only a literati “Utopia,” but also a revolutionary version of it by carving out a past in the future like Michel Foucault’s “Hetero-topia.”

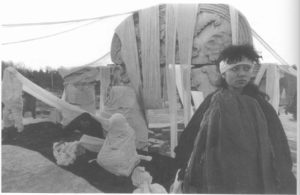

Concept 21, Liu Tao, 1988, Beijing, China

One example that stands out from this evanescent village would allow us to view the Cuban and Chinese artists in comparison. In 1988, village artist Liu Tao put up Concept 21, a performance involving wrapping architectural ruins and human bodies in white cloth and ribbons. While alluding to Christo and Jeanne-Claude, the French artist who famously wrapped the Arch of Triumph in Paris as L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped, Liu Tao’s work might also be an homage to the literati tradition of writing as critique. In ancient China, some literati officials would submit a critical essay to the emperor while simultaneously presenting and displaying other allegorical motifs in the act of submission. The motifs included the white cloth, a traditional signifier of the purity of heart and innocence and sacrifice. Following this route, white also represented death, funeral and commemoration, usually worn by the Chinese to attend a funeral or visit a friend’s or relative’s tomb on Tomb Sweeping Day, a national holiday. Moreover, the white cloth, especially made of brocade, was sometimes regarded as a gift of recognition from the emperor to acknowledge an official’s achievements. White clothing was also associated with the identity of Chinese intellectuals as appeared in many poems like Xiao Shan, a poem by the Song-dynasty poet Lu You, “The white clothing has protected me from getting the dirt of the capital,” which implies the integrated character of a classical Chinese literati who should always keep a critical distance from the power. Liu Tao conceptually adopted this form to revisit the literati legacy of the white cloth while forming an anachronistic tension with her time when the cloth was no longer allegorically meaningful but industrially produced to satisfy foreign markets. Additionally, the way of wrapping, which physically and historically connected the young student bodies, her body, and the architectural remnants of the garden, the injury of colonial conquest, was almost like “a constellation in motion.”[9]

It was also an “Essay on China,” composed of the fragments and pieces unified by a contingent performance. Additionally, it also paralleled the critical parity of the Americanist essay while being distinct from it, and simultaneously distinct from the literati tradition. In “an out-of-joint relation to its empirical context,”[10] Liu’s performance suggests the other layers of the work— “a risky proposal” to have a moment of mediation between “social reality, individual subjects, and the historical project of the Revolution.”[11] Similar to how Elso’s work discloses the contradictory nature of Cuba’s return to the Revolution, Liu’s work teases out the spurious continuity of Chinese history. The “new” reform of the Chinese Revolution by introducing Capitalism mechanisms as a pathway into the future is, only for the artists, a total rupture with the Revolution and literati history itself. Although seemingly unified by a visual continuity, the cloth, the architectural parts, and the young bodies drifted away from each other and acquired discursive identities to set the literati identity in immediate motion like Icarus’ flight. Like Pájaro que vuela sobre América, Liu’s elements “never quite synthesize” but drift apart as their state of being, making it more relevant to China in the 80s.[12]

A Group Photo of Yuanmingyuan Village Artists in the Early 1990s

Another example is the poetry of Hai Zi, which never lived in the village but also showed a similarly discursive identity as a “literati.” In a widely read and acclaimed poem entitled “Driving My Dream as a Horse,” Hai Zi, also a cultural icon of the 80s and fervent enthusiast of Chinese mythologies and esoteric practices, including the Taoist breathing exercise, wrote in the seventh paragraph of the poem: “If I were to be reborn in the riverbanks of my motherland in one thousand years, and if I were to have the rice paddies of China and the snowy mountains of Emperor Chou…….” By summoning Emperor Chou, important imagery in literati poetry, and a historical figure representing the epitome of the ancient wisdom of governance, often mythologized in many other contexts, Hai Zi revived the literati identity through himself but curiously put it in a distance from his current time. By setting this identity in the future (“in one thousand years”), he is mythologizing himself and this literati connection with a potential historical continuity people believed in. In other words, he is suggesting a future and fate of discontinuity as the rebirth but demands us to “hold the apartness” and bear along with him the pain of this process. “Driving My Dream as a Horse” stems from a Chinese myth that promised political continuity and literati ideals, but it only and eventually reminds us of Letatin, a “failed” flying machine Moreno also quoted in his essay as an example of irresolution and contradiction, “a good metaphor for its times,”[13] and registers deeper a parallel reality of Cuba and China in the 80s.

A Photo of Poet Hai Zi

The two examples bring us to the ultimate question— what can we find after making the comparison? Something unexpected? Some new relation between the two? It is surprising and generative to see a similar tendency to revive a historical tradition in the post-Revolutionary society almost with comparable fervor and idealism. However, this tendency will always fail to actually reconstruct and reconfigure history but end up forming a dialectical tension with it. Although both Cuba and China in the 80s remained Socialist nations, they chose to pursue different and almost opposite paths. In the two societies showing an extreme contrast, Cuban and Chinese artists both seemed to compose an “impossible” essay not to directly criticize the society but to seek an identity within themselves that was inherently incorporated by but eventually isolated from a grand yet contingent narrative.

After all, we shall revisit the question: were the Rectification (Cuba) and the Reformation (China) essentially opposite to each other? The convergence between the “essay” and the “literati” might lie in a similar response to the increasingly contingent character of the Revolution and history itself, constantly “renewed” by the past, be it Capitalism as in China or the Revolution as in Cuba. With the strained Cuba-China relationship troubled by China’s capitalist shift in the 80s turning congenial again in the 21st century, both Cuba and China learn to adapt to the global changes in a more profound and rapid way, yet the evanescent nostalgia of the past was rarely remembered again in today’s art, or at least, remembered only with more difficulty and fewer dimensions.

At the conclusion of the talk, Moreno exchanged his answers with Dr. Mansoor on the potential of Elso’s generation for our time, also a time constantly reshaped by renewal and crisis. He expressed his optimism about human creativity by returning to the discursive nature of symbols and history. By contrast, I would dare to propose a different answer: the matter does not reside in either future or the past because if we cannot return to humanity itself, we can only return to the fleeting pleasure of nostalgia that would comfort us but not lead us forward.

Footnotes:

[1] Susan Eckstein, “The Rectification of Errors or the Errors of the Rectification Process in Cuba?”, Cuban Studies Vol. 20 (1990): 67. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24486987.

[2] Gean Moreno, “One is Already Two, and Two are Many” for Dominance and Revolution: The image, the struggle and the use of force (talk, Valencia, CA, March 17, 2022): 1.

[3] Gean Moreno, “One is Already Two, and Two are Many” for Dominance and Revolution: The image, the struggle and the use of force (talk, Valencia, CA, March 17, 2022): 3.

[4] Gean Moreno, “One is Already Two, and Two are Many” for Dominance and Revolution: The image, the struggle and the use of force (talk, Valencia, CA, March 17, 2022): 13.

[5] Gean Moreno, “One is Already Two, and Two are Many” for Dominance and Revolution: The image, the struggle and the use of force (talk, Valencia, CA, March 17, 2022): 22.

[6] Gean Moreno, “One is Already Two, and Two are Many” for Dominance and Revolution: The image, the struggle and the use of force (talk, Valencia, CA, March 17, 2022): 17.

[7] Han Zun, “圆明园画家村:中国当代艺术家的漂泊之旅 Yuanmingyuan Yishujiacun: Zhongguo Dangdai Yishujiade Piaobozhilv [Yuanmingyuan Artist Village: the Diaspora of Contemporary Chinese Artists],” last modified October 8, 2018, https://posts.careerengine.us/p/5bbadbaaf46bd936379fabbb.

[8] Geremie Barmé, “A Romance in Ruins,” in The Garden of Perfect Brightness: A Life in Ruins (Canberra, Australia: Australian National University Press, 1996), 142-154.

[9] Gean Moreno, “One is Already Two, and Two are Many” for Dominance and Revolution: The image, the struggle and the use of force (talk, Valencia, CA, March 17, 2022): 1.

[10] Gean Moreno, “One is Already Two, and Two are Many” for Dominance and Revolution: The image, the struggle and the use of force (talk, Valencia, CA, March 17, 2022): 13.

[11] Gean Moreno, “One is Already Two, and Two are Many” for Dominance and Revolution: The image, the struggle and the use of force (talk, Valencia, CA, March 17, 2022): 25.

[12] Gean Moreno, “One is Already Two, and Two are Many” for Dominance and Revolution: The image, the struggle and the use of force (talk, Valencia, CA, March 17, 2022): 27.

[13] Gean Moreno, “One is Already Two, and Two are Many” for Dominance and Revolution: The image, the struggle and the use of force (talk, Valencia, CA, March 17, 2022): 28.

Bibliography:

Moreno, Gean. “One is Already Two, and Two are Many.” For Dominance and Revolution: The image, the struggle and the use of force. talk, Valencia, CA, March 17, 2022.

Barmé, Geremie. “A Romance in Ruins.” In The Garden of Perfect Brightness: A Life in Ruins, 142-154. Canberra, Australia: Australian National University Press, 1996.

Zun, Han. “圆明园画家村:中国当代艺术家的漂泊之旅 Yuanmingyuan Yishujiacun: Zhongguo Dangdai Yishujiade Piaobozhilv [Yuanmingyuan Artist Village: the Diaspora of Contemporary Chinese Artists].” Last modified October 8, 2018. https://posts.careerengine.us/p/5bbadbaaf46bd936379fabbb.

Eckstein, Susan. “The Rectification of Errors or the Errors of the Rectification Process in Cuba?”. Cuban Studies Vol. 20 (1990): 67-85. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24486987

— Written by Moham Wang

Bio:

Moham Wang is an alumnus from Rice University with a B.A. in Art History and graduate from California Institute of the Arts with an M.A. in Aesthetics and Politics. He’s pursuing his Ph.D. in Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

He’s a curator, artist and writer of Mien ethncity. Wang’s works can be found in Aesthetic Education, a national art journal in Asia.