OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

The Sneaker That Got Away: Chasing Identity $$

#CoronaQuarantine2020 allowed the West Hollywood Aesthetics & Politics lecture series audience to #zoom conference for the last Spring seminar on April 17. Hosted by the CalArts School of Critical Studies, the speaker for this event was Robeson Taj Frazier who is the Associate Professor at the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, USC. Mr. Frazier expanded on two readings, the first one centered on basketball culture in post-socialist China, and the second evaluates a sneaker subculture and how streetwear influences culture expansively, beginning in the 1970’s. The sneaker subculture readings offered me a chance to share some insights gleaned as I reevaluated the years I spent working in the fashion industry in NYC, after graduating from the Fashion Institute of Technology. I want to consider how identity is objectively produced through fashion, and how capitalizing on this paradoxically reflects gross consensus toward conformity as opposed to a singularity of the self.

HBO’s Entourage, performs a male-dominated character-driven comedy concerning a group of friends from “back East” who move to LA when one of them becomes a movie star. Friends of the main star remain-in-tow and each takes on a job of sorts working within the group. They live together in a variety of mansions in the Hollywood Hills, which we are vicariously meant to enjoy as they explore and indulge in the fantasies that come to life in the imagined world of a movie star. In short, the viewer is another one of the star’s entourage.

Episode 11 of Season 3, “What About Bob,” includes a secondary story-line of the character Turtle’s love affair with designer hard-to-get sneakers. The movie star, Vince, has a connection to a Japanese artist who creates specialty designs for Nike and commissions a one-of-a-kind pair for Turtle. After driving the entourage to a gangster-styled location in LA, Vince has Turtle step out of the SUV to go inside for a “pick-up.” Waiting in the SUV, Vince argues with the other guys about this extravagant purchase; “They’re not just sneakers, E., they’re wearable art,” states Vince, before confessing the 20K pricetag. Inside, Turtle is shocked to meet the Japanese graffiti artist Fukijama, who gives him the prized shoes, much to Turtle’s obvious delight.

The character of Fukijama is based on the musician-designer / producer Hiroshi Fujiwara and graffiti artist Futura 2000. The character’s situation performs for the viewer along on the ride, Hollywood’s version of an underground subculture. We experience access to a virtual designer cache, and the couture price tag sneakers such as these celebrity-artists manufacture IRL. This entertainment offers a couple of things for the viewer. It gives an indulgence in a life most can never achieve, connections they would never make, and through this discover the ‘finer’ things in life such as one of a kind $$ sneakers. They’re not just Keds anymore. But in resembling real life, the indulgence leans into possibility, the dreams of an always-achievable-in-America mentality, and the credit to purchase unaffordable illusions to specialness, one may not have or believe they possess. I want for you to realize this is the power of marketing, and whether that marketing is through a television show, an ad in a high fashion magazine, a famous sports-figure, or the hierarchy within subcultures where connection and ascription is oftentimes more important than family, values are made and a sense of self is crafted from the outside.

Fashion, which is ultimately what Turtle participates in through this purchase, seeks to navigate a clout in accessibility. It frames a fraudulent uniqueness, where exclusivity performs for others an individual’s wealth. It also infers intimate associations to the cultural distillations from a designer’s artistic vision. There is a hierarchy of specialness in the world of fashion, and artistic achievement lies beneath price, and that is corralled through the belief in the entire system upon which it is constructed. This is a system of capital, and works overtime in constructing belief through fantasies of want versus need, and crafts identity as an objective outside one is subjected to, but can never actually attain. If it was attainable, the illusions produced from marketing would collapse and true identity unreliant upon approval-seeking, or the need to “fit in,” could find resolve. Consider one such example I will use in working toward how this functions.

American designer Marc Jacobs has long been in the trenches of fashion, beginning in the mid-80’s. He has navigated the many pitfalls other designers would have never survived, including failed and bankrupt lines, somehow continuing and then thriving where others have been lost to the trade. The New York Times recently wrote, “Jacobs was just 29 when, in 1992, he showed his infamous grunge collection, which recast streetwear as luxury.” [1] The article continues in recognition of what this meant in terms of Mr. Jacobs as a creative force when summarizing that this particular collection, “…was only one of many instances when Jacobs would display his almost uncanny ability to identify the mood of a time, to give shape and form to what was yet unvoiced.” [2] This instance rests in the base production of the selling of fashion. ‘Identify the mood of the time.’ If one can plug into this zeitgeist before others, they are seen as hip, chic, and reflect this ‘know’ in their dress, what they wear and what they have. This reflects Turtle’s desire and want for those pricey sneakers, and the lengths some will go in order to participate in what may seem to others as frivolity. This participation appears as one who simply fits in with their peers. It also evidences a production of the self from the outside. Mr. Jacobs’ longevity, along with his creative and artistic talents, are owed in part to his comprehensive understanding of the business of fashion over the artistic side. He can read a zeitgeist forming, and designs accordingly for profit.

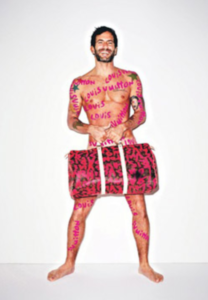

When Mr. Jacobs was hired to design for Louis Vuitton, he collaborated with the American-designer and peer Stephen Sprouse to graffiti-up their costly handbags with the day-glo marker style Sprouse popularised so effortlessly during the 1980’s. Jacobs was keenly aware of Mr. Sprouse. They were competitors during the 80’s and both had business struggles, and bankruptcies. Mr. Jacobs definitely registered the chic and hip cool vibe Sprouse lived in and produced with his own line. Jacobs brought Sprouse and his street-recognition style, and offered this to the world through his business relationship with Louis Vuitton. Jacobs recognized and capitalized on another cultural moment forming. His business savvy understood the artistic but profitable commercial value it held. What was it that Stephen Sprouse possessed in his artistic spirit, Mr. Jacobs foresaw that would be so valuable?

Stephen Sprouse came naturally from a streetwear aesthetic, having wound his way through the downtown scene. He garnered friendships through his assistant design position with Halston in the late 70’s that allowed him access to insiders’ affectations. He circuited clubs such as CBGB’s and The Mudd Club, and was friends with cultural underground writers like Tama Janowitz, the kids working at Warhol’s ‘factory,’ and other artists like Keith Haring, and Jean Michel Basquiat. After designing the dress Debbie Harry would wear in Blondie’s music video for Heart of Glass, a number one single released in 1979, Stephen Sprouse instantly gained, “the kind of exposure it had taken Halston years to get,” [3] as reported in New York Magazine, March 26, 2004. This can be considered as the precedent to an Instagram notoriety social media would monetize in a few more decades. The artist Andy Warhol soon became a fan, swapping two of his paintings for one of Sprouse’s entire 1984 collection. Sprouse was a darling of the New York fashion world all through the 80’s, becoming known for his marker-thick tagging (the term graffiti artists use when writing their moniker), dresses that appeared at first glance to be garbage bags, or mini t-shirts held together with safety pins. He brought day-glo to the marketplace, indicating his knowledge and connection to a hip street-aesthetic. His fashions were celebrated most dramatically in the movie, Slaves of New York, 1989, showing in one scene of the film the most recognized and vibrant, outrageous looks from his runway show that season. His designs became synonymous with the SOHO chic of the Art-World. That Art-World of SOHO, an already exclusive insider subculture, Sprouse knew how to navigate, and his designs connected the buyer to that world. This was the lightning in a bottle Marc Jacobs hired and had the wherewithal to capture and promote through Louis Vuitton, making millions for the company and taking them to another level of hipness, and attracting a much younger crowd. The buyer of those fabulous handbags would find an ascription to the world Sprouse inhabited, displayed their wealth to a public who recognized this, and participated in a street culture of the past revitalized and sold as fresh.

Stephen Sprouse exemplified through his designs what we can consider ‘fashion-up.’ Some would call it trickle-up – the inverse of trickle down, a socializing concept regarding the wealthiest elite whose fashions literally trickle down to the poorest of the poor, who when they finally can afford the elite fashions, the fashion is resultantly, dead. Fashion-up is a concept used to describe particular subcultural stylistics popularized on the streets, which are then copied by major houses and found later on runways in New York, Paris, Milan, and Tokyo. It can be described as ‘streetwear,’ which similarly follows this transference of style, as found from a subculture of sneaker-fashion. “The growing popularity of sneakers led to the formation of a legitimate fashion genre called “streetwear,” notes Yuniya Kamawura. Kamawura continues, citing Steven Vogel in her book, Sneakers: Fashion, Gender, and Subculture, “Streetwear represents a lifestyle that many agree was born in the early 1980’s in New York. Due to the constant alienation and frustration felt mainly by inner city kids, not just in New York but worldwide, a community was formed that was influenced by skateboarding, punk, hardcore, reggae, hiphop, and emerging club culture, graffiti, travel and the art scene in downtown city areas.” [4]

Streetwear has a much older history however, and I could cite the influence of Elvis’s rockabilly style in 1956 as such. This ‘streetwear’ forms on the search for identity one seeks in freedoms taken rather than offered. Styles that came not from a designer’s fashion line, but from a putting together on one’s own in following the shared leads within a subculture group, and the decided need to separate oneself from their parents generation. It began to change the direction from which a designer must gather their inspirations.

When the celebrated couturier Christian Dior changed hemlines and skirt volume, literally overnight with his iconic “New Look” in 1947, it was born on the freedoms returned after war-time restrictions regarding allowable skirt yardage. During WWII, the War Production Board established Order L-85, in order to reduce textile use in garment production by 15 percent. “For women, skirts had to be at least 17 inches above the floor and slacks had to have narrow legs. Hems and fabric belts could be no more than two inches wide, and no garment could have more than one pocket,” as posted in the online resource Historynet. [5] Mr. Dior simply gave the ladies what the cultural moment offered: longer voluminous skirts. This was a soft, flowing, flower-like reprieve after the tight, militant, hard-shouldered look the ladies had been wearing during the difficult war years. This examples fashion-down, and a time when a designer’s dictates were exclusive to independent thinking.

Streetwear never influenced Mr. Dior, but he demonstrated how cultural availabilities effect change, and its reflections through fashion. This can dictate skirt lengths, and transform what we take for sex appeal. Stylish looks and ideas for how one can dress erupted later when teens rivaled cultural tastes, as exampled through Elvis; greased back pompadours for boys, and tight capri length slacks for girls. They looked to one another for how to conform, and this transformation was socially mediated through music performance. The Dior’s in the industry and their moral coterie were aghast, but smart designers would soon learn to follow leads from youth culture, from subcultures, from the urban movements of a quickly changing world. The influence of popular music and the identity-seeking teens who support it, provide an insight into those smaller subcultural moments that micro-effect styles, fashions, and in turn broaden corporate means to dilute these aesthetics into capital-productions for the masses. Subcultural sneaker-hipness has changed how you and I purchase sneakers, because the design has been dictated not by a designer, but by the subculture itself, which has been copied and then diluted by the corporate entity, such as Nike.

Fashion requires numbers in order for it to germinate from conceptual idea, to mass produced thing, that ends resultantly because of the popularity that made it fashionable in the first place. Because it is paradoxically elusive, exclusive, nuanced, and made to be sold to the most people possible right before it becomes overnight, ‘unfashionable,’ it is composed of ephemeral cultural responses that navigate the fine line between a proximity to bad taste and extreme play of proportion in regards to the human body. Some examples would be; nipped in waists dramatically juxtaposed against unrealistically wide shoulders, enormous blouses placed atop the slightest place-mat of a skirt, or long tight “cigarette” pants under oversized boxy jackets or loose, too-large sweaters that all demonstrate this proportional play and the majority of means through which a designer efforts changes in turn causing the public to continue having a need for “New.” Of course we could walk down runways of the past where corsets, paniers, and hoop skirts hassled ladies like horses clipped and prodded for show, maintaining not just a figurative aesthetic unlike the actual human body underneath, but also foreclosing all other designs considered good fashion, but I think we all get the picture I am working toward efforting. People want to stand out because of connotations to a ‘cool’ aesthetic, being ‘with-it,’ and the perception of exclusivity, and at the same time, want to fit in. This paradox demonstrates how capitalising through changes in fashion, whether from trickle-down, or trickle-up, produces a need for identities belonging, even though striving toward differentiation. All would like to think and believe they are within a specialized entourage of an aligned coterie of uniqueness, a subculture if you will of in-the-know. But fashion defies this belief with mass production. Some fashion ‘Houses,’ or ‘lines,’ as they are commonly known in the industry, have managed to bring their name to the forefront of popular presence, and their Name becomes what is fashionable. Chanel, Fendi, Gucci, Versace, Schiaparelli, Halston, Calvin Klein, and Donna Karan, are some named examples of designers, Houses if you will, who manage to bring their name to such a position of fashionability and clout, so that almost whatever they design or place their Name-Brand on as label, sells.

It is this idea of House that was idealized and documented in Paris is Burning. This film follows an underground culture formed from the many discarded trans and queer urban youth who follow and claim an allegiance to a particular House, named after or in honor of couture houses and fashion icons. Each House is a small made-family of unrelated but socially similar kids, who become known within this subculture for the House they are from. This film was reimagined and invigorated through the subculture of drag and the show RuPaul’s Drag Race, that the writer and producer Ryan Murphy established a hit with the television show Pose, taking the storyline and character driven drama as inspired from Paris is Burning, directly. One becomes confused at this point what exactly is underground, which came first, and where did a particular subculture style such as the idea of Vogueing as performed by the kids documented in the film, then the songstress Madonna, and lastly, a re-performance of this in Pose. What I want for consideration here is the transmovement when streetwear – and here I want you to understand in this particular instance it isn’t just ‘wear,’ it is also dance, style, music, relationship, gender, and new concepts of being ; this entire subculture is trended upward, then diluted and gentrified for mass appeal, and turned into an everyday capitalized phenomenon, that all have access to and can recognize, but for most of whom its very origins are lost.

Louis Vuitton – Stephen Sprouse Collection Kicks

Nike is one such Name-Brand company who produces sought-after sneakers, aka: kicks.

They also produce sportswear-inspired fashions that are now becoming more and more vogue, especially as people are covid-secluded and staying at home all day requires a further comfort these casual but trendy looks offer. ABC news magazine, Nightline, offered insight into a secondary sneaker market prompted through the manufacture of limited-supply, specially designed kicks. This limited supply sells out rapidly in stores, and in turn not unlike concert tickets where buyers purchase blocks of seats for higher resale value later, these kicks get re-sold at mini-conventions held regularly where kids purchase secondhand for hundreds more than retail. Often, hopeful buyers camp out overnight, at times even for days, on sidewalks outside specialty stores, prior to release of these newly-designed sneakers. Nightline also highlights this as performed on the HBO show Entourage, where we see Turtle shopping with his friend Vince along one such site in LA.

Demand becomes infectious through desire for a thing that is hard to get. They demonstrate purchase power and access to exclusivity within a subculture. The mini-conventions they attend where limited edition sneakers are sold, have at times produced a mass panic. Would-be buyers crash gates to entrances causing damage and injury. As a result Nike began selling their specialty shoes online only. As one boy discovers in the Nightline segment, Nike’s entire inventory sells out within seconds. After logging in through several false accounts this boy managed to purchase one pair of prized Nike’s. A pair he will most likely re-sell at the weekend conventions he routinely participates in, for much more than he had to shell out for online.

Self named DJ Clark Kent has been in the sneaker subculture since the late 1970’s, and has amassed some 2500 pairs of shoes, as Nightline, reports during their interview. “These kids today don’t want the shoes, they want the “thing,” that goes along with the shoes,” Mr. Kent states.

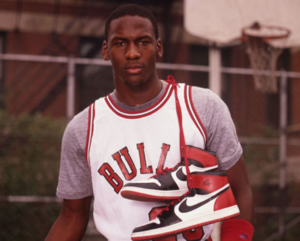

Nike has long held prominence in the sneaker-trade business. Retailers, fashion experts, and culture watchers all can name the moment when Michael Jordan and Nike collaborated together in promotion of both entities, but using Mr. Jordan’s star power and athletic abilities most effectively as the selling point.

A 2018 advanced copyright-proof of author Mr. Nicolas Smith’s book, Kicks: The Great American Story of Sneakers, effectively records the stylistics of an advertising campaign for Nike Air Jordans:

‘It’s gotta be the shoes.’ Most people have heard it, even if they can’t remember the source: a 1989 commercial for the Nike Air Jordan IIIs. In the commercial, Spike Lee, playing his alter ego Mars Blackmon from the movie She’s Gotta Have It, lists all the possible reasons Michael Jordan is ‘the best player in the universe.’ His dunks? asks Lee. No, Mars, says Jordan. His shorts? asks Lee. No, Mars, says Jordan. His bald head? asks Lee. No, Mars, says Jordan. His shoes? asks Lee. Jordan denies it, but Lee keeps circling back to the shoe guess. In the thirty-second ad, the word ‘shoes’ is spoken ten times. Before the familiar swoosh appears on screen, a cheeky disclaimer informs us that ‘Mr. Jordan’s opinions do not necessarily reflect those of Nike, Inc.,’ but everyone already knows the message here: ‘It’s gotta be the shoes.’ [6]

A teenage boy viewing this would have numerous cultural evidences to behold. Mr. Lee, whose prominent film is used in promotion of the Nike product, performs Mr. Jordan’s physical specificity as embodied through his athletic production in the game of basketball. This boy may not have the same physical attributes as Mr. Jordan – and almost no one else has – and therefore can never experience the athletic performance Jordan can. He may not have the multi-million dollar access this generated for Mr. Jordan, he may not even have any athletic ability whatsoever. But he can, perhaps, gain a perceived access to this through an allegiance provided in a purchase of his Air Jordans as they are known. Mr. Lee captures this desire of want for escapism and perpetrates this toward a very specific customer who would know and get the message.

One might ask Mr. Lee, who is the audience? I am certain Nike and its advertising company, Weiden & Kennedy, who has held Nike’s campaigns since prior to Mr. Jordan’s involvement, comprehended a purview of marketing and sales potentials which they delegate with a specificity not unlike an oil company does in drilling for new wells. Adbrands, a global accounting of advertising companies and their results, demonstrates how Nike’s sophisticated and nuanced understanding of cultural particulars, creatively promote their brand through this exclusive production. A June 2019 report in following Nike’s achievements help to indicate exactly this facility:

Only three days in, and Nike collected its fourth grand Prix of the 2019 Cannes Lions with a clever Media campaign in Brazil, coordinated by AKQA and Weiden & Kennedy. AKQA got local graffiti artists to spraypaint an exclusive custom-designed pair of Nike Air Max trainers onto their work in different areas of Sao Paulo. Nike then told customers they could order the limited edition shoes via their app, but only from the location of the graffiti. A GPS signal from their smartphones confirmed their positions and opened a special ordering page in the app. [7]

Now you may ask yourself as I did; who is this in Sao Paulo that owns an iPhone, with appropriate apps and the purchasing power giving one an access to the costly and limited edition sneakers, whose existence is only known while one is located in graffiti laden areas? How does recognition of the graffiti artist’s use of sneaker-brand affiliation, advocate for ascription to uniqueness – such as the graffiti artists strive to produce, and in turn promotes shoe sales for Nike? For the love of God, who needs this shit? The fucking Amazon was burning out of control this past summer, and Nike is digging for gold in impoverished areas.

LINK: Nike advertising & marketing profile

The necessity of owning a device for which access through social media platforms, such as apps in order to have purchase power, when purchase power initially meant one only had to have cash, is a postmodern mix one had not the need for prior to Nixon obliterating the gold standard. Now concepts of credit, or capital as evidenced in the exchange of data through cellular communication and body tracking, not just bio-politically efforts constructions against any ideal of anonymity and personal sovereignty, but justifies this through conscriptions hidden in the guise of conformity and self-diminishment. The performance artist Laurie Anderson sings about trees mechanically produced to, “chop themselves down,” [8] in her 1984 hit, Sharkey’s Day. It seems this is now performed through a subculture affiliation that once would have been free of monetization or capitalized through corporate positioning of the made-consumer. It appears instead to be a kind of self-colonization. Now, the colonizer doesn’t have to take over a particular place and population, but relies upon the person alone, the subcultures crafted, to colonize themselves through ascription into an idealized belief of specialness through hard earned monies paid. It is like that famous line in the horror movie When A Stranger Calls, 1979, “we’ve traced the call. It’s coming from inside the house.”

Michael Gardner is an artist and writer. He recently completed his thesis for the MA in Aesthetics and Politics at CalArts titled, Portrait of the Artist As A Young Gay Man: A Congruence of Events. He invites you to visit his website www.MichaelGardnerArt.com, his blog RunsWithBrushes.blogspot.com, and his images of random note on Instagram @GardnerMichael.

Carter, Ash. “KICKS The Great American Story of Sneakers By Nicholas Smith.” New York Times Book Review 123, no. 27 (2018): 19–19.

Laurie Anderson. Sharkey’s Day. Warner Records, n.d. https://genius.com/Laurie-anderson-sharkeys-day-single-edit-lyrics.

Adbrands. “Nike Advertising & Marketing Profile,” n.d. https://www.adbrands.net/us/nike-us.htm.

Patricia Morrisroe. “The Punk Glamour God.” New York Magazine, March 26, 2004.

“The Many Lives of Marc Jacobs.” The New York Times Style Magazine, February 10, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/10/t-magazine/marc-jacobs.html.

Thelin, Alexandra. Sneakers: Fashion, Gender, and Subculture., 2016.

[1] “The Many Lives of Marc Jacobs,” The New York Times Style Magazine, February 10, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/10/t-magazine/marc-jacobs.html.

[2] “The Many Lives of Marc Jacobs.”

[3] Patricia Morrisroe, “The Punk Glamour God,” New York Magazine, March 26, 2004.

[4] Alexandra Thelin, Sneakers: Fashion, Gender, and Subculture., 2016.

[5] “How America Got Its Citizens to Ration Clothing During WWII,” n.d., https://www.historynet.com/hemmed-in-conversation-efforts.htm.

[6] Ash Carter, “KICKS The Great American Story of Sneakers By Nicholas Smith,” New York Times Book Review 123, no. 27 (2018): 19–19.

[7] “Nike Advertising & Marketing Profile,” Adbrands (blog), n.d., https://www.adbrands.net/us/nike-us.htm.

[8] Laurie Anderson, Sharkey’s Day (Warner Records, n.d.), https://genius.com/Laurie-anderson-sharkeys-day-single-edit-lyrics.