OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Hobnobing with Boots Riley and Sarah T. Roberts Over Arnold Palmers in Temescal

Hobnobing with Boots Riley and Sarah T. Roberts Over Arnold Palmers in Temescal

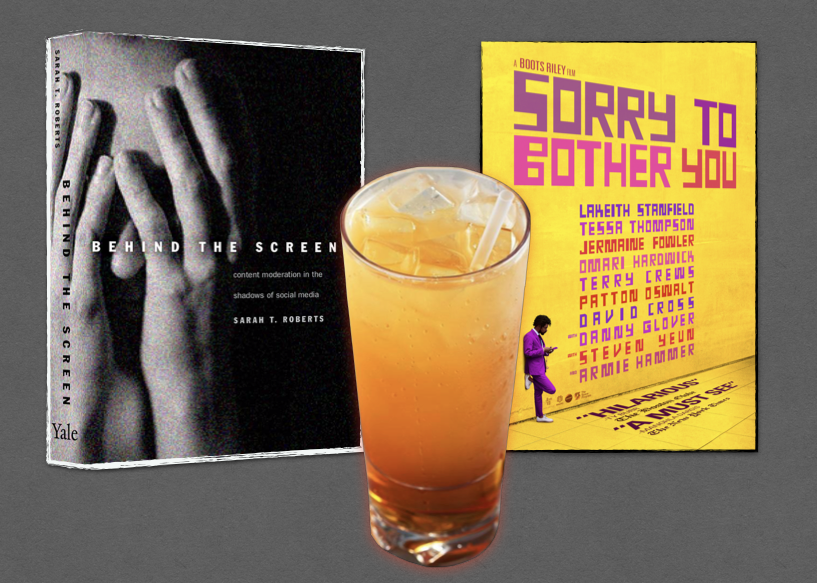

As part of the West Hollywood Aesthetics and Politics lecture series, Sarah T. Roberts and Dr. Safiya U. Noble shared the West Hollywood Public Library stage on October 25th. The event was a convergence for the CalArts massive, but it was also a platform for the work being done at UCLA, as Roberts and Noble both teach in Westwood and are co-directors of the University’s Center for Critical Internet Inquiry. Roberts spoke on the topic of commercial content moderation (a line of research that includes her recent book, Behind the Screen) while Noble (author of Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism) facilitated the discussion by posing questions and reflecting on her own research in relation to the work of Roberts.

Noble was an effective and value-added interlocutor for the lecture, although I had imagined a different interlocutor beforehand. While reading Behind the Screen, I kept thinking about Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You. They share similarities, and are also very different. Both are about hidden labor—the subtitle for Roberts’ book is “Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media,” and Riley has described his film as “an absurdist dark comedy with aspects of magical realism and science fiction inspired by the world of telemarketing.” Dissimilarly, they use the divergent platforms of the university publishing press and fictional film. And although neither places its creator at the center of the work, they both have traces of the personal, as Roberts initially provides a personal frame for her work in the story of how an article in the New York Times led to her interest in content moderation, and Sorry to Bother You was inspired by the filmmaker’s experience working as a telemarketer.

In thinking about how Roberts and Riley could be brought to the center of a shared discourse—a discourse further influenced by fiction’s potential for insight—I decided to bring Riley and Roberts together for an imaginary evening. Michael Holly has called thinking one unlike thing with another the most powerful form of inquiry in the humanities, so in addition to the possible clash between the different ways in which they approach their work, I wanted to frame the conversation with additional contrasts that were grounded in reality or absurdism. Inspired by the setting of Sorry to Bother You, the following episode takes place in Oakland, at a neighborhood bar that specializes in the combination of iced tea and lemonade. (While gentrification in Temescal is real, I haven’t been to any Arnold Palmer bars there… yet.)

. . .

According to the flickering neon sign that drew patrons within, the name of the bar was ‘Late Capitalism.’ The names of those with whom I shared a table were Sarah T. Roberts and Boots Riley. Over the course of the evening, I gathered that Roberts had watched Sorry to Bother You and may have heard some of The Coup’s albums, but it was never clear how Riley knew about Roberts’ work. The first thing that I remember was them talking about was “the process” and whether evidence or ideology was the best starting point for a project. I jumped in, explaining how I once wrote an art column for the Rockridge News and was thinking about developing a new series. I don’t think that they were exactly impressed, but they agreed to let me take notes as they talked, and quickly fell back into the discussion.

Ideology Versus Evidence

Taking up contrasts in ideology and evidence, Riley said that he felt publicly identifying himself as a Communist was important and that it could engage the audience who might listen to his music or see Sorry to Bother You. He said using that specific term could challenge the audience to think about what Communism could mean, perhaps even going further than sharing the particular message that he might have held as an intention for an album or film. Riley described this type of inspiration as a way of putting energy into a larger process and that having a band called “The Coup” was a type of manifesto in itself. He said that with ideology as a starting place, his work was meant as advocacy for change. Roberts initially responded that evidence has an irrevocable primacy since she operates in academia and her point of entry was the study of information, although she hoped that her approach to the material would be capable of engaging the general reader. Unlike Zizi Papacharissi’s work which approaches a close reading of raw data, she hoped that her work was breathing life into the hidden labor supporting social media networks. She briefly asked Riley if it wasn’t evidence that had informed his ideology, but acknowledged that that was less of a critical concern since they were circulating around ideas of process and product.

Roberts then refocused the discussion by comparing her research on commercial content moderation to Riley’s work with the world of telemarketing in Sorry to Bother You. She understood how part of Riley’s inspiration for the film was from his experience as a telemarketer and that he had the room as a filmmaker to go from this world into an absurdist dark comedy, especially since it was a job that was more-or-less imaginable for audiences. Roberts then stated that although fiction could produce something meaningful, so could evidence-based work; that even when the information is obscured by corporations as in the case of commercial content moderation where working conditions and even locations can be unclear, the need for the effort alone illustrates the importance of the work.

Film in Fiction and Fact

In response to commercial content moderation as shadow labor, Riley turned the conversation to place it in relation to film. He said that film could only talk about shadow labor for so long, and although there are opportunities for suspense in cinema, a filmmaker channeling Hitchcock wouldn’t be able to use commercial content moderation for a feature-length work. He then cited Sergei Tretyakov on film either having a cultural role in providing a confrontation with reality or otherwise functioning as aesthetic hashish in providing an escape from reality. Riley said that Sorry to Bother You acts as a critique of reality since it puts characters in a situations where they can be a mirror for contemporary society. He also said something about the possibility of playing aesthetic hashish against itself, that it’s something audiences associate with the medium, and that he was able to use touches of Magical Realism in order to make bigger points about the ramifications of the exploitation of labor. Riley then claimed that works of creative fiction could tell important stories that aren’t possible for straightforward research and empirical evidence.

Countering the argument for Magical Realism, Roberts began by noting how the main character in Sorry to Bother You was also developed through self-reflection and existentialism. She talked about how even in a fictional work there had to be something available to audiences that could humanize the characters, even if the filmmaker had created a relatable situation. Roberts talked about being an academic advisor for the documentary The Cleaners, and how the most relatable characters are people who exist in the world and already are mirrors for contemporary society. She then argued that the extended ramifications of commercial content moderation were scarier than most products of Magical Realism since interfacing with digital information has become our general cognitive strategy. Those interfaces, Roberts said, depend on real people who work in dehumanizing conditions and serve a type of oracle that has been called an “object of faith” by Alexander Halavais. She claimed that as far out there as Sorry to Bother You might be, there are common systems of operation being used by the social media giants now that are almost as disconcerting as the indentured servitude and genetic mutilation used by WorryFree, the film’s antagonist corporation.

Both of them appearing to reach points of agreement, Riley picked up on the issue of transparency and internet-based corporations. He said that although exploitation of labor is nothing new, he could understand why Roberts had been so focused on content moderation. Riley conceded that his initial concern about waiting for evidence when creative opportunities to support change were already apparent had lessened during the conversation. He cited recent news items that challenged the lack of transparency in the status quo, including leaks to the media from Amazon warehouses about working conditions and Mark Zuckerberg testifying before Congress about Facebook’s use of moderators and cryptocurrency ambitions. Riffing further off of the topic of corporate transparency, Roberts cited the “object of faith” concept against Google’s history of violating user privacy, search neutrality, and corporate transparency.

Riley and Roberts went on to debate how close we might already be to a WorryFree reality. They excitedly began putting the pieces of a new picture together: a story about commercial content moderation building from industrial labor exploitation à la Fritz Lang’s Metropolis up to the scene in The Wizard of Oz when the Wizard pleads for Dorothy and friends not to look behind the curtain, although, as a counterpoint to the myth of Captain Cook’s ships being invisible to the first people his expedition met off the coast of Australia, the protagonists can no longer see what is behind the curtain. Illustrated here by a fantasy climax are the real-world consequences for the continued exploitation of information-processing labor and information itself: dystopias of capitalism and cognition.

. . .

I may never fully grasp what could bring the three of us together over the combination of iced tea and lemonade. In Riley’s published script for Sorry to Bother You, the foreword references Hollywood executives having a penchant for banana daiquiris. And in the script’s closing acknowledgments, Riley writes: “I owe you all a drink or dinner at a place that’s not too expensive.” (Roberts isn’t in the acknowledgments—unless under a pseudonym?) In the first sentence of Behind the Screen, Roberts mentions having an iced latte. Would an Arnold Palmer be an acceptable substitute for an iced latte?

Carl R. Schmitz is an art historian who really did write a column for the Rockridge News. His preferred search engine is DuckDuckGo.

Further Reading and Watching

Works Cited or Circulating

Alexander Halavais. 2018. Search Engine Society. Cambridge: Polity. ?

Michael Holly in James Elkins, Zhivka Valiavicharska, and Alice Kim, eds. 2010. Art and Globalization. The Stone Art Theory Institutes, V. 1. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press (p. 107). ?

Safiya Umoja Noble. 2018. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: New York University Press. ?

Zizi Papacharissi. 2017. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press. ?

Boots Riley, Nina Yang Bongiovi, Forest Whitaker, Charles D. King, George Rush, Jonathan Duffy, Kelly Williams, et al. 2018. Sorry to Bother You. Beverly Hills, Calif.: Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment. ?

Sarah T. Roberts. 2019. Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ?

Sergei Tretyakov. 1927. “Бьем тревогу” / “We Raise the Alarm” in Новый Леф / New Lef (pp. 2–5); Translated by Ben Brewster, “Documents from Novy Lef” in Screen 12(4), Winter 1971-72. Oxford: Oxford University Press (p. 70). ПДФ, PDF, ?