OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

From Marathon to Casamance: Rethinking Conservation as Political Resistance

This essay serves as an anticipatory reflection on Aby Sène’s lecture, “Wilderness Aesthetics and the Erasure of Black Cultural Landscapes from Georgetown, South Carolina to Casamance, Senegal.”1 This analysis examines the complex interrelationship between conservation, cultural landscapes, and memory preservation. It draws on literary, philosophical, and political perspectives to reflect on the various levels at which conservation and restoration operate. Analyzing colonizers and colonized people’s cultural landscapes, the contribution emphasizes the political urgency to safeguard surviving remnants of marginalized groups in the face of colonial erasure. Influenced by Aby Sène’s work, these pages reveal how conservation can act as a means of resistance and cultural survival.

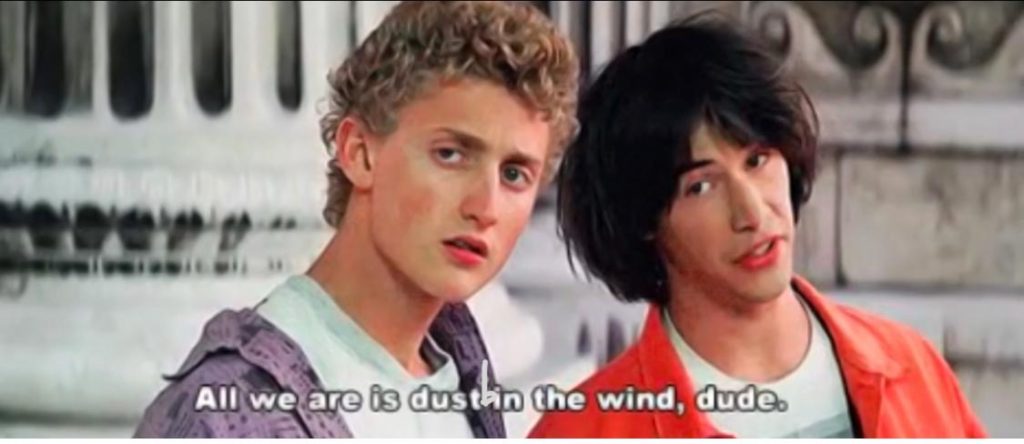

An ancient folk tale tells of travelers passing through the plain of Marathon (figure 1), by land or sea, and hearing neighs of horses and men fighting at night. In Pausanias’s account,2 the story takes on spiritual overtones: the travelers seem to actually see the ghosts of the ancient warriors repeating their battle over and over again. In Ugo Foscolo’s “Dei Sepolcri,”3 on the other hand, the vision takes on a more romantic tone, ending with the poet’s benevolent envy of his friend Ippolito Pindemonte, who had witnessed such a spectacle in his youth.

While the veracity of such apparitions is debatable, this story tells us of a feeling we have all experienced when in contact with a place we hold dear. In particular, it makes us reflect on the emotions that can arise when confronted with a natural landscape loaded with historical and cultural values. Without claiming that one can see ghosts in Marathon, it is certainly true that the awareness of being in the place where—two and a half thousand years ago—the fate of the West was decided can’t help but send shivers down the spine.

Tha plain of Marathon today. Detail of the Tumulus of the Athenians excavated in 1884.

For this reason, in the European context, I have always appreciated those archaeological sites where the decay of the traces from the past was naturally present. Believing the artificiality of certain conservative interventions to be superfluous and distasteful, I have often praised those places capable of conveying the grandeur of a people even without the presence of visible remains. For example, I found the Palace of Knossos in Crete particularly repugnant: brought to light in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the site has been profoundly reconstructed, creating a misleading appearance of authenticity and concealing its natural deterioration. Instead, I very much liked the sites of Delphi and Epidaurus: examples of more conservative interventions, while still reversing the course of time, they create a more natural balance between the environment and the becoming of history. In Delphi, although there have been many environmental interventions—think of the construction of the on-site museum—once inside the site, visitors perceive the magical valley and its ruins with a certain ease. Fences, signs, and the displacement of certain artifacts certainly do disrupt the relationship between traces and nature that time has created. However, unlike at Knossos, there are not such strong signs of artificial staging. Similarly, the remains of the city of Epidaurus—not the theater—harmoniously integrate the ruins and the surroundings. With almost no fencing, the visitor walks across a field, encounters the remains of the great Greek civilization, and is amazed by the concrete manifestation of Anaximander’s logos—according to the offense committed, everything pays the price of its existence, returning to the original indeterminacy.4

From top to bottom, the archeological sites of Knossos, Delphi, and Epidaurus in Greece.

In other words, reflecting on the European context, I have always appreciated the possibility of being moved by and understanding the past from what history has handed down to us directly. Perhaps too fascinated by a form of evolutionary fatalism, I have always perceived the anti-becoming effort that preservation entails as a profoundly hubristic act. That is, I have always considered the question of the relationship between preservation, remains, and memory on a metaphysical plane. Mainly focused on the Greek scenario, I never clearly perceived the possibility of understanding this relationship on different planes.

However, a recent encounter with Aby Sène’s texts and the title of one of her lectures made me develop an alternative perspective. When we look at texts like “A Holistic Framework for Participatory Conservation Approaches”5 and analyze them with the gaze of someone critical of conservation activities, these essays seem to rest on fragile foundations. Indeed, the explanations of how different types of intervention simultaneously help local societies and the permanence of their history seem to take the goodness of conservation for granted. At this point, however, the title of the aforementioned intervention—“Wilderness Aesthetics and the Erasure of Black Cultural Landscapes from Georgetown, South Carolina to Casamance, Senegal”—opens up new possibilities.

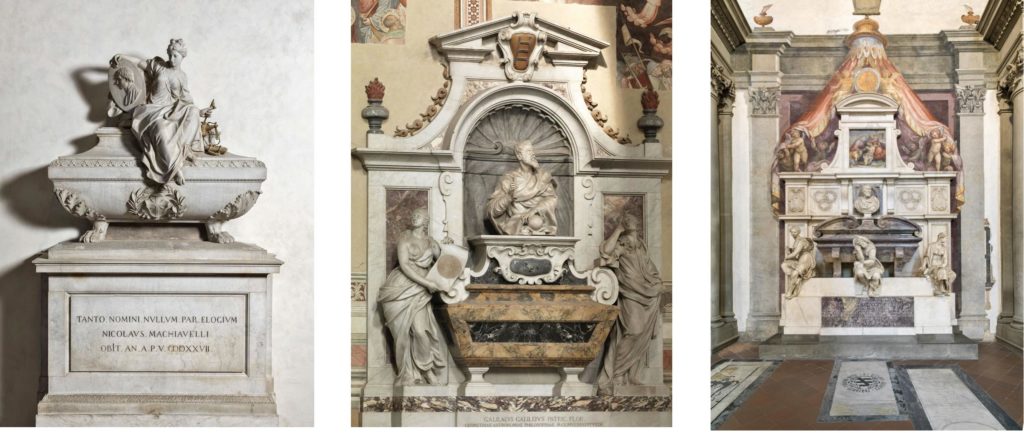

In “Dei Sepolcri,” Foscolo already suggested the peculiarity of the Greek case. “Testimonianza a’ fasti eran le tombe, ed are a’ figli” (vv. 97-8 “Tombs were witnesses to past glories and altars for future generations”), says the poet about the original function of graves. While his poem accurately describes the presence of numerous tombs of brave people in both Italy and Greece, there is a significant difference between those of the two nations. Whereas in the first 200 lines about Florence and Milan the presence of the stone on which to mourn the dead is fundamental (figure 3), it is not as important in the case of the heroes of Marathon. In the Troad and Attica, the mere knowledge that something has happened in a certain place and the simultaneous perception of that space are enough to evoke certain emotional states. Contrary to Napoleon’s “Décret impérial sur les sépultures” (Saint-Claude, 06/12/1804 and extended to the Italian provinces in September 1806), which prescribed burial outside the city walls in neutral graves for all, Foscolo describes how the Muses wander in vain in search of the remains of their beloved Giuseppe Parini, buried in “plebei tumoli” (v.70, “the meanest graves”). Instead, the memory of Priam’s sons seems to endure forever, despite the disappearance of the physical component of their tombs. It is the landscape—the landscape that witnessed their actions—that symbolizes and transmits their heroic deeds into eternity.

From left to right, the monumental tombs of Niccolò Macchiavelli, Galileo Galilei, and Michelangelo Buonarroti in Santa Croce in Florence. These are the sepulchers that Foscolo had in mind when describing Vittorio Alfieri being inspired by the Italian heroes buried in Florence.

Now, reflecting on the causal link Aby Sène proposes between the aesthetic ideal of “wilderness”6 and the erasure of Black landscapes, one precisely realizes why the metaphysical arguments developed in relation to the Greeks do not apply equally to all peoples. The search for a natural fusion between the environment and human traces, which in Greece may lead to the acceptance of the fading of the traces without any consequence, becomes in other contexts an ideological act of erasure. In this sense, all the judgments and considerations on the preservation and restoration of these people’s past must embrace moral and political analyses.

While the fate of Greek civilization and its existence in historical memory is not determined by physical traces, the case is different for African peoples or Native Americans. In fact, the Greek myth is a structural part of the world’s dominant ideology, and therefore, its permanence is not defined by the presence of physical objects. Instead, since the culture of the various colonized peoples is antagonistic to the dominant one, it is only through something material that they can affirm their imprint on the world and pass down their memory. In this sense, preservation and restoration do not mean opposing the becoming of nature, but resisting the ideology of the Western colonizer. Ensuring that one’s traces are not erased by an imposed ideology means fighting the cultural annihilation proposed by certain dominant paradigms.

From this new perspective, conservation takes on an unprecedented value and importance. If the act of preservation exists simultaneously on two levels—metaphysical and political—it opposes both the logos of nature and human cultural erasure. Thus, while conservation is objectionable in the former sense, it is praiseworthy in the latter. While it may seem hubristic to oppose the becoming of nature, when it turns out that this logos and other similar concepts are often ways through which certain cultures stand as arbiters of the histories of others, resistance is justified and necessary.

Aby Sène’s research on how best to intervene in the natural environment while preserving the human traces of Indigenous peoples is thus implicitly justified. In her essays, the absence of an argument about why it is right to conserve and the subsequent focus on which methods to adopt has an implicit reason. In a world where one group of people believes that their own values are universal and therefore does not care about those of others, defending a diverse cultural landscape does not mean looking to the past in an antiquarian way7, but embracing the future. In the hands of those who defend and preserve these landscapes, history and its relics are the fulcrum of an action directed toward the upcoming times. If an archaeological site in Greece is useful for scientific purposes and human curiosity, the material remains represent the possibility of existing tomorrow for oppressed peoples.

For these reasons, shifting focus from the cultural landscapes of colonizers to those of colonized peoples necessitates a change in the approach to the questions of conservation, restoration, and protection. If the metaphysical level and the problem of the laws of nature are appropriate in the first case; in the second, the question must necessarily be brought to a more practical level. In the second context—that of oppressed cultures—preservation is not an extra but a necessity: preservation is not an archival fad but the only way to survive. Hence, in line with Aby Sène, the key questions regarding Black cultural landscapes in Africa and the U.S., as well as Indigenous territories globally, are not about why they should be preserved, but how they can be preserved. In these contexts, the real question is how to make conservation a maximally effective political action.

The “House of Slaves” on Gorée Island, Senegal (picture by Ko Hon Chiu Vincent, 2017) was a key site in the transatlantic slave trade, where enslaved people were held in brutal conditions before being sent to the Americas. Built in 1776, it now serves as a museum and memorial, offering a way to reflect on the atrocities of slavery and remember its victims. This site is a successful example of what, in the essay, I called “political conservation.”

Endnotes

- The lecture will take place on Friday, December 6th, 2024 at the Radical Hood Library in Los Angeles, CA, as part of the California Institute of the Arts Lecture Series: “Deconstructing the Police” ↩︎

- Pausanias (c. 110 – c. 180) was a Greek geographer of the second century AD ↩︎

- Ugo Foscolo (Februrary 6th, 1778 – September 10th, 1827) was an Italian writer and poet ↩︎

- Symplicius, On Aristotle Physics, 24,13 “ἐξ ὧν δὲ ἡ γένεσίς ἐστι τοῖς οὖσι, καὶ τὴν φθορὰν εἰς ταῦτα γίνεσθαι κατὰ τὸ χρεὼν· διδόναι γὰρ αὐτὰ δίκην καὶ τίσιν ἀλλήλοις τῆς ἀδικίας κατὰ τὴν τοῦ χρόνου τάξιν” (“from where the beings have their origin, there, according to necessity, they also find their destruction: they pay one another the penalty and the expiation for their injustice, according to the order of time”) ↩︎

- See also Aby Sène-Harper, David Matarrita-Cascante, and Lincoln R. Larson, Leveraging local livelihood strategies to support conservation and development in West Africa, in Environmental Development 29 (2019), 16-28. And, Aby, Sène-Harper, Justice in nature conservation: Limits and possibilities under global capitalism, in Climate and Development (2023), 1-10 ↩︎

- Consider the role played by the “Wilderness Act” of 1964 in the definition of this ideal ↩︎

- See Friedrich Nietzsche, Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen. Zweites Stück: Vom Nutzen und Nachtheil der Historie für das Leben (1874) ↩︎

Bibliography

- Foscolo, Ugo. Dei Sepolcri

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Use and Abuse of History. Arlington: Richer Resources Publications, 2010

- Pausanias. Description of Greece

- Sène-Harper, Aby, David Matarrita-Cascante, and Leslie Ruyle. “A holistic framework for participatory conservation approaches.” International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 26, no. 6 (2019): 484-494

- Sène-Harper, Aby, David Matarrita-Cascante, and Lincoln R. Larson. “Leveraging local livelihood strategies to support conservation and development in West Africa.” Environmental Development 29 (2019): 16-28

- Sène-Harper, Aby. “Justice in nature conservation: Limits and possibilities under global capitalism.” Climate and Development (2023): 1-10

- Symplicius, On Aristotle Physics