OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

Notes on the American Police Procedural

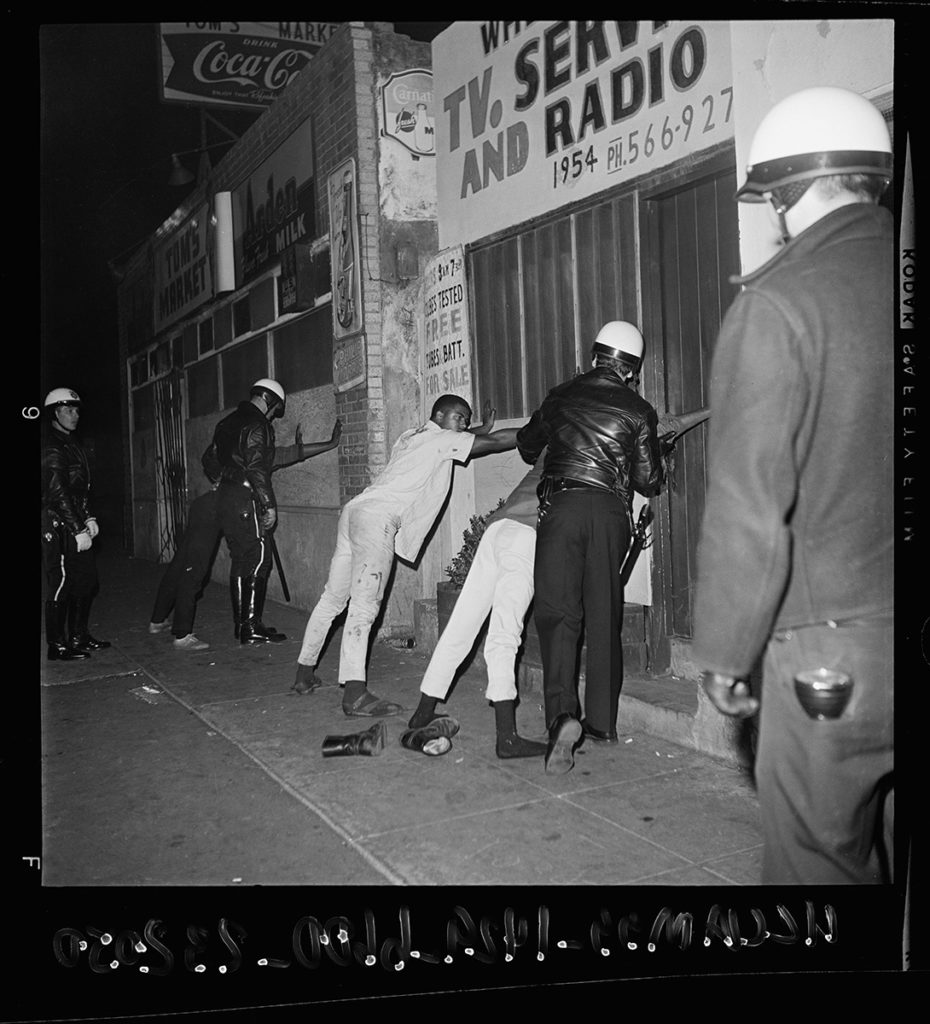

Speaking in October 2024 at the Radical Hood Library in Los Angeles as part of the “Deconstructing the Police” lecture series presented by the MA Program in Aesthetics and Politics, organizer Matyos Kidane outlined a history of the surveillance practices employed by the Los Angeles Police Department, including tactics of behavioral profiling that have disproportionately subjected Black, immigrant, and working-class Angelenos to multiple forms of police violence: intimidation, psychological and bodily harm, arrest, incarceration, and death. These tactics of surveillance and behavioral profiling function on aesthetic grounds, relying on assumptions about visual perception and interpretation in order to categorize actions or individuals as criminalized, deviant, or worthy of punishment. Like the slogan “See something, say something”—famously championed by the Department of Homeland Security and law enforcement agencies as part of an “anti-terrorism” campaign in the wake of 9/11—instances of police surveillance demonstrate the inextricability that twines together questions of aesthetics and politics, asking how what we see and how we see it comes to signify a story with specific consequences for the distribution of power.

Kidane, an organizer with the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition, briefly discussed the close collaborative relationship between Hollywood and the LAPD, particularly throughout the creation of Dragnet (1951-1959, 1967-1970), the midcentury television show generally recognized as the progenitor of the genre known as the “police procedural.” While critical theorists, conspiracy theorists, and cops are all prone to practicing what Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick calls “paranoid reading” [1], such suspicious conjecture is not necessary in the case of the LAPD and Dragnet—the involvement of the police in the show’s production is readily apparent in both the historical archive and the explicit framing the show provides for itself, demonstrating the central role played by the LAPD in the creation of one of the earliest and most enduring works of copaganda. [2]

In terms of its pervasive reach and central role in defining the police as characters in the American cultural imagination, the most obvious successor to Dragnet is Law & Order (1990-2010, 2022-present), which began airing on the same network, NBC, thirty-nine years after its predecessor. A common characteristic shared by the two shows is the formulaic way in which each episode contains familiar narrative beats that shape superficially idiosyncratic events into a consistent, coherent form: law and order, action and consequence, crime and punishment. For viewers who find comfort in watching police procedurals, this familiar narrative structure—its neatly predictable contours, charged with the frisson of potential surprise—is likely the source of the relief we feel. Chaos, fear, and unpredictability that can be meted out in regular rhythms and portions across an hour of television, buttressed by clear outcomes and moral boundaries, serves as an inoculation against the inscrutability of the fleeting, ambiguous impressions offered by daily life.

Of course Law & Order is not alone in adapting and modifying the police procedural; dozens of other scripted American TV shows have contributed to the genre:The Untouchables (1959-1963), Police Story (1973-1978), Hill Street Blues (1981-1987), Miami Vice (1984-1990), Homicide: Life on the Street (1993-1999), the CSI franchise (2000-2016), and Brooklyn Nine-nine (2013-2021), among many others. The emphasis falls differently in each of these iterations—Brooklyn Nine-nine, for example, belongs as much if not more to the genre of the workplace comedy as it does to the police procedural. (Think The Office with guns.) Yet urgent questions remain: if your goal is merely to luxuriate temporarily in the familiar structure of the procedural, in whatever form it appears, how much do you risk internalizing propaganda that benefits—and, in broadly genealogical terms, was crafted by—the police? How does the procedural format, with its pat beats and predictable structure, normalize certain narratives of crime and punishment as linear, rational, comfortably classifiable? Is there a hypothetical television show that provides the procedural pleasures of Law & Order alongside a stringently anti-cop message? How do we let the dun-dun hit—that satisfying auditory punctuation—while also saying, “Fuck the police?” [3]

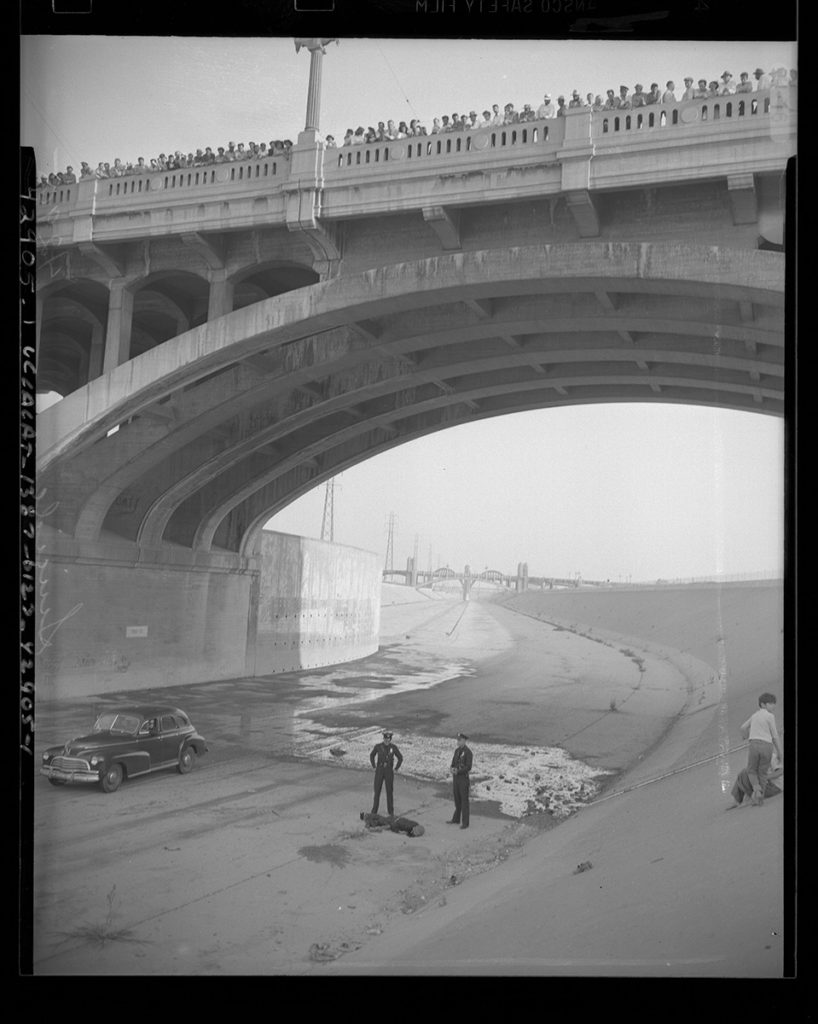

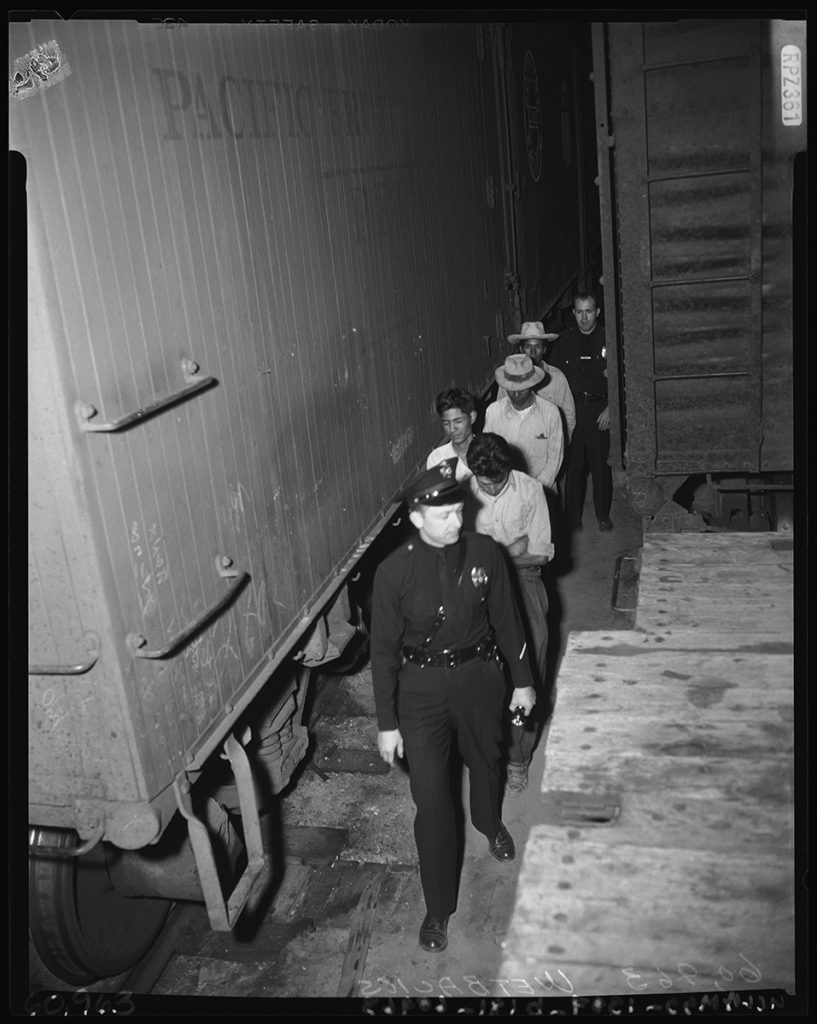

The images accompanying the following notes were all retrieved from the UCLA Library Digital Collections and originally appeared in either the Los Angeles Times or the Los Angeles Daily News between 1947 and 1967. The standard captions provided by the archives index each image.

1.

In 1948, American radio actor Jack Webb had a small on-screen role as a crime-lab technician in He Walked By Night, a film based on the real-life killing of California Highway Patrolman Loren Cornwell Roosevelt two years prior. He Walked By Night belongs to a particular postwar American subgenre of “semi-documentary” films, meaning they were generally drawn from real events and filmed on location. The production of these “semi-documentary” films also often involved the participation of the law enforcement agencies involved in the original case. Detective Sergeant Marty Wynn of the Los Angeles Police Department provided “technical assistance” for He Walked By Night, which became a commercial success for its distributor Eagle-Lion Films.

Writing in the stalwart Hollywood rag Variety, a contemporary reviewer praised He Walked By Night upon its release:

“Starting in high gear, the film increases in momentum until the cumulative tension explodes in a powerful crime-doesn’t-pay climax. Striking effects are achieved through counterpoint of the slayer’s ingenuity in eluding the cops and the police efficiency in bringing him to book. High-spot of the film is the final sequence, which takes place in LA’s storm drainage tunnel system where the killer tries to make his getaway.” [4]

2.

Inspired by the success of He Walked By Night and the collaboration with Sergeant Wynn, Webb proposed a radio drama portraying the work of the LAPD in a similarly “semi-documentary” style. The resulting program, Dragnet, would go on to become the most famous and influential American crime drama of the second half of the twentieth-century, formulating the conventions and concerns of the genre that would eventually be known as the “police procedural.” Both in its initial radio format and later on television, Webb starred as the series’s protagonist, Sergeant Joe Friday.

3.

Film historian Christopher Sharrett has written that “He Walked By Night… would become Dragnet’s stylistic template, from its semi-documentary style down to its opening title card that read, ‘The names have been changed—to protect the innocent.’” [5] The opening narration of each episode of Dragnet features the line “The story you are about to hear is true”—anticipating a similar line in the opening narration of Law & Order, which would not premiere on television until 1990: “These are their stories.”

4.

From its emergence as a distinct narrative genre, the American police procedural claims to tell essentially real stories, despite whatever degree of dramatization is involved. (See also: “Ripped from the headlines.”)

5.

Before pitching Dragnet to the NBC radio network, Webb familiarized himself with the day-to-day operations of the LAPD, frequently visiting police headquarters and joining Sergeant Wynn on “ride-along” night patrols with his partner Officer Vance Brasher. The actor also attended police academy courses to learn official law enforcement jargon and gain a sense of the details of a criminal investigation that could be shared with the public.

6.

An essential component of Webb’s vision for Dragnet was gaining the endorsement of the LAPD: he wanted to dramatize events from official case files and “authentically” portray the actions taken by police during their investigations. In 1949, Webb received the support of then LAPD Chief Clemence B. Horrall. In return for this endorsement, the LAPD sought control over the program’s sponsor and demanded that the police would not be depicted in an unflattering light.

7.

When Dragnet premiered on the NBC radio network in 1949—where it continued to air until 1957—it featured a standard voiceover introducing the program after the first commercial break: “Dragnet, the documented drama of an actual crime. For the next thirty minutes, in cooperation with the Los Angeles Police Department, you will travel step-by-step on the side of the law through an actual case transcribed from official police files. From beginning to end—from crime to punishment—Dragnet is the story of your police force in action.”

This preamble’s usage of the second person—you and your—creates a visceral sense of personal proximity between the listener and the events being dramatized, heightening perceptions of both imminent danger and verisimilitude. The narration in certain episodes places this proximity to the action—and potential agency within it—even more forcefully upon the listener. The episode “Big Saint” (airing on April 26, 1951) begins: “You’re a detective sergeant. You’re assigned to auto theft detail. A well-organized ring of car thieves begins operations in your city. It’s one of the most puzzling cases you’ve ever encountered. Your job: break it.“

8.

During Dragnet’s initial run as a radio drama, Webb attracted the support of William Parker, who became Chief of the Los Angeles Police Department in 1950 and would serve in this role through 1966—making him the longest-serving LAPD police chief to date. Before forming a partnership with Webb and Dragnet, Chief Parker produced a panel show affiliated with the LAPD called The Thin Blue Line. He frequently appeared as a panel member on the program to proclaim the role of police in protecting civil society from the forces of criminality.

9.

In his 1990 book City of Quartz, historian Mike Davis calls Chief Parker “an avowed white supremacist held responsible by Los Angeles Blacks for a police reign of terror.” [6] Davis goes on to describe how, “as reformed in the early 1950s by legendary Chief Parker… the LAPD was intended to be incorruptible because unapproachable, a ‘few good men’ doing battle with a fundamentally evil city. Dragnet’s Sergeant Friday precisely captured the Parkerized LAPD’s quality of prudish alienation from a citizenry composed of fools, degenerates and psychopaths.” [7]

10.

After premiering on NBC in December 1951, many of the earliest Dragnet episodes directly adapted radio broadcasts that had previously aired—in some cases, actors lip-synced along with dubbed audio. In addition to continuing to star as Sergeant Friday, Jack Webb directed every episode of the show, which was filmed at Walt Disney Studios in Burbank. This first iteration of the series aired on television from 1951 through 1957, when Webb shifted his focus to developing other projects for his production company. He later revived the series for a second run from 1967 through 1970, and a television movie intended as the revival’s pilot aired in 1969.

11.

In 1966—only a few years before he began composing Anti-Oedipus with psychoanalyst Félix Guattari in the wake of the events of May 1968—French philosopher Gilles Deleuze wrote “Philosophy of Série Noire,” a short text discussing a publishing imprint dedicated to releasing hard-boiled crime fiction in France. Founded in 1945 by actor Marcel Duhamel, Série Noire popularized Anglo-American detective novels by writers such as Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett with French readers. With all its titles featuring a stark black cover, the imprint is believed to have inspired French film critic Nino Frank to coin the phrase “film noir” in 1946 to describe Hollywood crime movies.

In “Philosophy of Série Noire,” Deleuze writes, “A society is indeed reflected in its police and its crimes, while at the same time it safeguards itself from them through profound collaborations… The Série Noire has familiarized us with this combination of business, politics, and crime which, despite all evidence of ancient and modern history, had not yet received its current literary expression.“ [8]

12.

Sharrett, the film historian, describes Webb’s Sergeant Friday as “the television incarnation of the paranoid style in American politics. The ‘other’ is omnipresent, especially in the 1960s series. Webb’s lengthy establishing shots of the smog-laden LA cityscape show us not the generic ‘naked city’ shielding criminals but, rather, an image of a normal world that can be easily capsized by those who don’t belong—which in Webb’s vision includes much of the population… In Dragnet 1967, Webb has a full array of ‘others’ who serve as raw meat for his angry, voracious ideological appetite: hippies, protestors, pot smokers, black militants, liberal intellectuals, and a gaggle of miscellaneous social misfits constitute an army of opposition that is always the fantasy life of the Right.” [9] [10]

13.

In the early 1980s—following the presidential election of former Hollywood actor and California governor Ronald Reagan—Jack Webb was working on another revival of Dragnet, preparing to return yet again to his role as Sergeant Joe Friday. Following his death from an unexpected heart attack in December 1982, plans for this second revival of the series were abandoned. LAPD Chief Daryl Gates announced that badge number 714—Sergeant Joe Friday’s badge number in Dragnet—would be retired. Badge 714 had previously been worn by LAPD Lieutenant Dan Cooke, who served as a technical advisor and department contact during the production of the revived Dragnet of the late 1960s. The badge used by Webb in his portrayal of Sergeant Friday is now on display at the Los Angeles Police Academy. As reported by the Los Angeles Times in April 2024, the LAPD currently has roughly 8,000 sworn officers—and it appears unlikely that the organization will be able to reach Mayor Karen Bass’s stated goal of retaining 9,500 LAPD officers anytime soon. [11]

Today—over seventy-five years after Jack Webb appeared as a crime-lab technician in He Walked By Night, inaugurating his career-spanning collaboration with the LAPD—another genre has joined the police procedural and the “semi-documentary” film in claiming to tell real stories. It’s right there in the name: true crime. Although established as a television genre by shows such as Cops (1989-present), true-crime stories are now most commonly encountered in the form of podcasts, such as Serial (2014-present) and My Favorite Murder (2016-present). In addition to providing a familiar narrative structure akin to that of the police procedural, true-crime podcasts and their internet fandoms often appeal to amateur sleuths who sometimes become involved in investigations themselves, leading journalists to question whether these self-appointed detectives accomplish more harm than good. [12] There’s been a murder in your town. It’s one of the most puzzling cases you’ve ever encountered. Your job: solve it.

[1] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid You Probably Think This Article is About You,” included in Touching Feelings: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 123 – 152). [2] Scholars Jessica Hatrick and Olivia González have attributed the first use of the phrase “copaganda” to blogger Greg Beato, “who wrote in 2003 that ‘mostly Hollywood has simply churned out malignant copaganda that glamorizes police brutality and normalizes the idea that the only good cop is a bad cop’” (Jessica Hatrick and Olivia González, “Watchmen, Copaganda, and Abolition Futurities in US Television,” Lateral, Vol. 11, No. 2, Fall 2022). [3] See also: “The Theme of Law & Order” by Mike Post (1990) and “Fuck tha Police” by N.W.A., from the album Straight Outta Compton (1988). [4] Variety, staff review, 1948. [5] Christopher Sharrett, “Jack Webb and the Vagaries of Right-Wing TV Entertainment,” Cinema Journal, Vol. 51, No. 4 (Summer 2012), 165. [6] Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (London: Verso, 1990), 126. [7] Ibid., 251. [8] Gilles Deleuze, “Philosophy of Série Noire,” translated by Timothy S. Murphy, Genre: Forms of Discourse and Culture, Vol. 34, 2001. [9] Christopher Sharrett, “Jack Webb and the Vagaries of Right-Wing TV Entertainment,” Cinema Journal, Vol. 51, No. 4 (Summer 2012), 167. [10] See also: Richard Hofstadter, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” Harper’s, November 1964. [11] Libor Jany, “LAPD’s recruiting woes laid bare: Only 30 officers per class, analysis shows,” The Los Angeles Times, April 20, 2024. [12] Phoebe Lett, “Is Our True-Crime Obsession Doing More Harm Than Good?,” The New York Times, October 28, 2021.