OPEN ASSEMBLY

Experiments in Aesthetics and Politics

[ pending ]

[ pending ]

[ pending ]

[ pending ]

[ pending ]

[ pending ]

[ pending ]

[ pending ]

[ pending ]

[ pending ]

[ pending ]

On October 23, 2020, Professor of Media, Culture, and Communication Nicholas Mirzoeff will give a public lecture as part of the West Hollywood Aesthetics and Politics (WHAP) series. Aria Dean of Rhizome will respond to the lecture and a conversation will follow. The Fall 2020 Lecture Series, “Black Out: On the Surveillance of Blackness,” is presented by the CalArts School of Critical Studies and the West Hollywood Public Library. The lecture will be held virtually at 4:30 PST and can be viewed live.

Introduction

On March 13, 2020, 26 year-old Breonna Taylor, a Black woman, was killed by police in her Louisville, Kentucky home. Taylor’s murder occurred only three months into a year already marred by egregious violence against Black Americans at the hands of both state and nonstate actors. Though each occurrence is unique—both in terms of the context in which the murder took place and in terms of the singularity of a human life and the irreversible, extraordinary loss of that singular life—the year 2020 has laid bare the linkages between white supremacy, law enforcement, and Black death in the United States. The inarguably heinous nature of Taylor’s murder was a catalyzing event. In the days, weeks, and months following her death, people all over the world took to the streets with calls to say her name.[1]

As demonstrations continued after Taylor’s murder, social media once again took up its role as an outlet for information dissemination, fundraising efforts, and resource sharing. With its myriad capabilities and near-ubiquitous use, social media (a term I am hereafter using to specifically reference Instagram and TikTok) is an undeniably powerful tool in the global movement against anti-Black racism. But social media also has a consumerist slant, and content is carefully curated to appeal to material desires. Scrolling through Instagram, one may encounter stylish infographics on mutual aid efforts and well-lit selfies spliced between ads for razors. As a commercially-oriented digital mode, social media feeds are an amalgamation of self-selected content and sponsored advertisements. Accordingly, Breonna Taylor’s name has been made into memes and posted between 30-second quarantine cooking challenges. With regard to the seriousness of Black death and white supremacy, is this total aestheticization what is meant when we are told to say her name?

In the movement against anti-Black racism, encounters with social media must be informed by the historical impulse to consume the Black body. Necessary in this undertaking is a shift in how the act of seeing is understood. Nicholas Mirzoeff defines seeing as “the intersection of what we know, what we perceive, and what we feel, using all senses.”[2] In this formulation, all senses are involved in the act of seeing. The visual field is filtered through other sensorial experiences and influenced by pre-existing judgements and emotions. Through social media aestheticization, Black death and pain are made continuously visually available. This perpetuates the identification of the Black body as both consumable and possessable.

Reference and Refusal: Aunt Hester’s Scream

Social media demands culturally-recognizable aesthetics in order to be rendered visible. The context or purpose of the post becomes secondary to how it appears to the viewer. Everything becomes consumable, whether it is for sale or not. As a result, social media has become a contemporary outlet for the spectacle of Black death. Though the intention may be to demand justice and ensure remembrance, the consumerism of Breonna Taylor’s name and likeness perpetuate the cultural anti-Blackness that contributed to her death. Art has always been a powerful mechanism for activism, but the inherent consumerism in social media aesthetics risks degrading the seriousness of the issue at hand: historical, rampant, and legally-sanctioned violence against Black people in the United States.

Concerns surrounding the reproduction of Black suffering and death are not exclusive to social media. In the introduction of Scenes of Subjection, Saidiya Hartman outlines her argument for how slavery continues to live on after manumission. A crucial formal element to her argument is her refusal to textually reproduce the beating of Aunt Hester in Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick. Douglass’s account of the beating has been made into one of the most prolific scenes of torture in the literature of slavery, used to aesthetically illuminate the centrality of violence in the creation of the slave subject and elicit empathy from readers for the abolitionist cause.[3] Hartman predicts the reader’s desire to consume details of the violence that Aunt Hester endured. She then meets the impulse to possess the Black body by inhabiting it through white empathy with a refusal. She questions how one is expected to participate in dramatizations of anti-Black violence:

Are we witnesses who confirm the truth of what happened in the face of the world-destroying capacities of pain, the distortions of torture, the sheer unrepresentability of terror, and the repression of the dominant accounts? Or are we voyeurs fascinated with and repelled by exhibitions of terror and sufferance? […D]oes the pain of the other merely provide us with the opportunity for self-reflection?[4]

Here, Hartman challenges whether witness and voyeurism are very different at all. Behind this argument is the claim that the acute horrors of anti-Black violence cannot be (re-)represented. Consequently, those who willingly put themselves into a position of witness only engage in a contemplation that is tied to an inappropriate preoccupation with the violence itself. Hartman’s questioning of the dues of spectatorship suggests that anti-Black violence is sustained when Black suffering is made into a spectacle for optic consumption. The reproduction of Black pain becomes a mechanism for normalizing Black death as something routinely consumable.

The Problem of “Awareness-Raising”

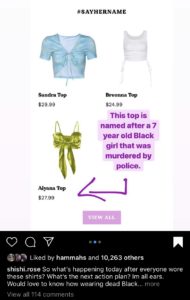

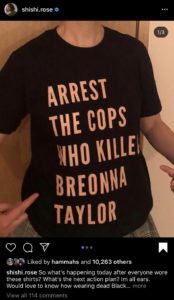

The murder of Breonna Taylor activated responses on social media on an unprecedented scale. Calls to arrest her killers and invocations to “say her name” continued months after her death. As time went on, content emerged that reflected the flippancy with which Hartman warned regarding the aestheticization of Black death. Similarly concerned, writer, birth worker, and educator ShiShi Rose reposted to her Instagram a series of images that exemplified the inappropriate commodification of Black women under the guise of awareness-raising.

The first image showed an unnamed clothing brand’s #SayHerName line of shirts. The blue and white shirts are named for two Black women who lost their lives after coming into contact with police. Rose writes onto the image that the third shirt, the “Aiyanna Top”, references Aiyana Jones, who was only seven years old when she was killed by Detroit police in 2010. To name a commodity after a deceased Black child ascribes particular value to the object while degrading the humanity of Aiyanna Jones. Through the context of its naming, “Aiyanna Top” is given a unique affective value that can be obtained for $27.99. One is meant to feel that purchasing and wearing the “Aiyanna Top” is a homage to Aiyanna Jones, but the two have no meaningful relation. Further, the garment appears more like a bra than a “top”, recalling the sexualization of Black girls.

The shirt in the second image features a modern sans-serif text in a subdued pink. The simple layout and muted colors evoke the minimalist design speak to how social media aestheticization works to diminish the statement that it references. It has been designed for an Internet-literate buyer who, after purchase, wears the shirt to feel a disproportionate sense of pride for bringing “awareness” to Breonna Taylor’s murder. By loosely gesturing Black death through clothing, Black death is aestheticized and Black women and girls become literal commodities.

Under the guise of raising awareness, commodification degrades the gravity of anti-Black violence. They also suggest that these murders can somehow be remedied with a purchase. Rose problematizes the impact of “awareness-raising”, asking how a shirt emblazoned with a dead Black woman’s name reflects any meaningful efforts to dismantle anti-Black racism or prevent more Black death.[5] She questions if such displays are effective means of activism, on or off the Internet. After the shirt is bought and the photo is posted, are Brett Hankison, Myles Cosgrove, and Jonathan Mattingly any closer to accountability? Are the right people hearing us say her name, or are we making ourselves inaudible?

“I need YOU to…” Aesthetic Demands for Justice

To discuss social media’s foibles is not to deny its revolutionary impact in the realms of political activism and art. On the flip side of vulgar consumerism, there are resources for abolitionist politics that have become part of a global commons. For example, activists can collaborate across state borders and record videos that reach thousands (or millions). Artists across disciplines also digitally engage with social movements and have a platform for their work to be widely disseminated, without having to be played on the radio or land a major gallery show. It is through the democratizing capacities of social media that it can be made politically useful and, in turn, marshal a different set of aesthetic sensibilities.

Tobe Nwigwe, a Black musician from Houston, Texas, strategically utilizes the video sharing platform TikTok to advocate for Breonna Taylor. His video, “I NEED YOU TO (BREONNA TAYLOR)”,[6] has garnered hundreds of thousands views on TikTok and YouTube. Within a 60-second time limit, Nwigwe uses sparse production and understated design to keep viewers focused on a single message.

The camera is at eye-level as the frame slowly widens to include two women on either side of Nwigwe. The simple, seated choreography appeals to the immense popularity of dance videos on TikTok, and the inclusion of subtitles makes the video’s message even more explicit.

The temporal distance between but “I need you to” and the action “arrest the killers of Breonna Taylor” requires the full attention of the viewer. Viewers are removed from passive roles and made to feel that they, personally, have an obligation to attain justice for Breonna Taylor and Elijah McClain.

The video suggests that reproduction does not invariably make a spectacle of Black death, even when pain is referenced. This perspective is supported by Fred Moten in In The Break, when he considers Hartman’s decision to not reproduce the beating of Aunt Hester. He asserts that the beating of Aunt Hester is already reproduced through Hartman’s initial reference to it, despite her putative refusal.[7] What Hartman’s refusal does, perhaps paradoxically, is address Black pain in a different register in order to counter its normalization. Moten brings attention to how reproduction is always-already occurring, from the moment it is made relevant, even through its absence.[8] Once again considering Nwigwe’s reproductive performance, it can be seen how “I NEED YOU TO (BREONNA TAYLOR)” disrupts what Hartman refers to as the terror of the mundane and quotidian[9]—the irreverence of Black pain that makes Black death routine. Nwigwe meets the viewer’s consumptive gaze with his own and intervenes in the normalization of Breonna Taylor’s murder.

Seeing for Future Worldbuilding

In “The Murder of Michael Brown: Reading the Ferguson Grand Jury Transcript,” Nicholas Mirzoeff analyzes the evidence used in the 2014 trial of police officer Darren Wilson. Through an examination of several photographs and courtroom transcripts, Mirzoeff exemplifies how visual information is strategically utilized to build a narrative. This narrative insulates and enforces state power, casting Black people as liable for their own deaths and legitimizing police discernment. The prosecution’s narrative served to protect Wilson and vilify Brown, effectively proving that what is seeable is both biased and constructed. This implies that the act of seeing is not passively taking in visual information. To see is to become implicated in the enforcement of a narrative.

If we are committed to the narrative that (All) Black Lives Matter, we must move away from all anti-Black impulses. This includes using social media as a digital forum for the spectacle of Black death. There is an ethics to the digital world. Memes are not proof of anti-racist virtue. A repost is not an all-encompassing call to action. And, surely, buying and wearing a shirt is not a demand for justice.

Mirzeoff contends that in the year after Michael Brown’s death, Black Lives Matter activists have created a new way of seeing. It is understood as a collective way to see, visualize, and imagine.[10] This way of seeing is a practice of persistence, especially when it is unpleasant or painful. It recognizes the visual field as historical and political, and as such, it is a method for building a world liberated from anti-Black racism and white supremacy. To move forward into this world, a shift must occur in how we see in the virtual world. How can gestural and consumptive impulses become disruptive? How can the aesthetic (re)performativity of social media be made productive? What would it mean, then, to say their names?

Endnotes

- “Say Her Name” was created in 2015 to bring attention to violence against Black women in the United States. Since 2015, the phrase has maintained prominence on social media and in protest.

-

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. “The Murder of Michael Brown: Reading the Ferguson Grand Jury Transcript.” Social Text 34, no. 1 (March 2016): 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-3427129.

-

Hartman, Saidiya. “Introduction.” In Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Ninteenth-Century America, 3–6. Race and American Culture. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/campuspress.yale.edu/dist/1/2391/files/2018/03/Race-and-American-Culture-Saidiya-V.-Hartman-Scenes-of-Subjection_-Terror-Slavery-and-Self-Making-in-Nineteenth-Century-America-1997-Oxford-University-Press-2h0let9.pdf.

- Hartman.

-

Rose, ShiShi. Instagram, August 11, 2020.

-

Nwigwe, Tobe. I NEED YOU TO (BREONNA TAYLOR). YouTube video, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qCzxWZVrtDc.

-

Moten, Fred. “Resistance of the Object: Aunt Hester’s Scream.” In In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, 1–24. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2003. https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/campuspress.yale.edu/dist/1/2391/files/2018/03/Moten-In-the-Break-11j1uox.pdf.

- Moten.

- Hartman.

- Mirzoeff.